What would you do with a few bottle caps? Discard them, I presume. But 39-year-old Harminder Singh Boparai uses such discarded pieces to create stunning works of art.

His latest work, titled Life, consists of discarded bottle caps which he has used to make a fish sculpture.

What’s unique is how each piece of art he has created has an inspiration and story behind it. His sculptures seamlessly integrate modern and traditional ideas.

Harminder crafts his works of art from scrap metal and discarded materials, and has won many national and international accolades and awards for his work both nationally and internationally. Being left partially paralysed at the age of 11 did not deter his artistic creativity in any way. If anything, he only worked harder to carve a niche for himself.

Is academic excellence the be all and end all?

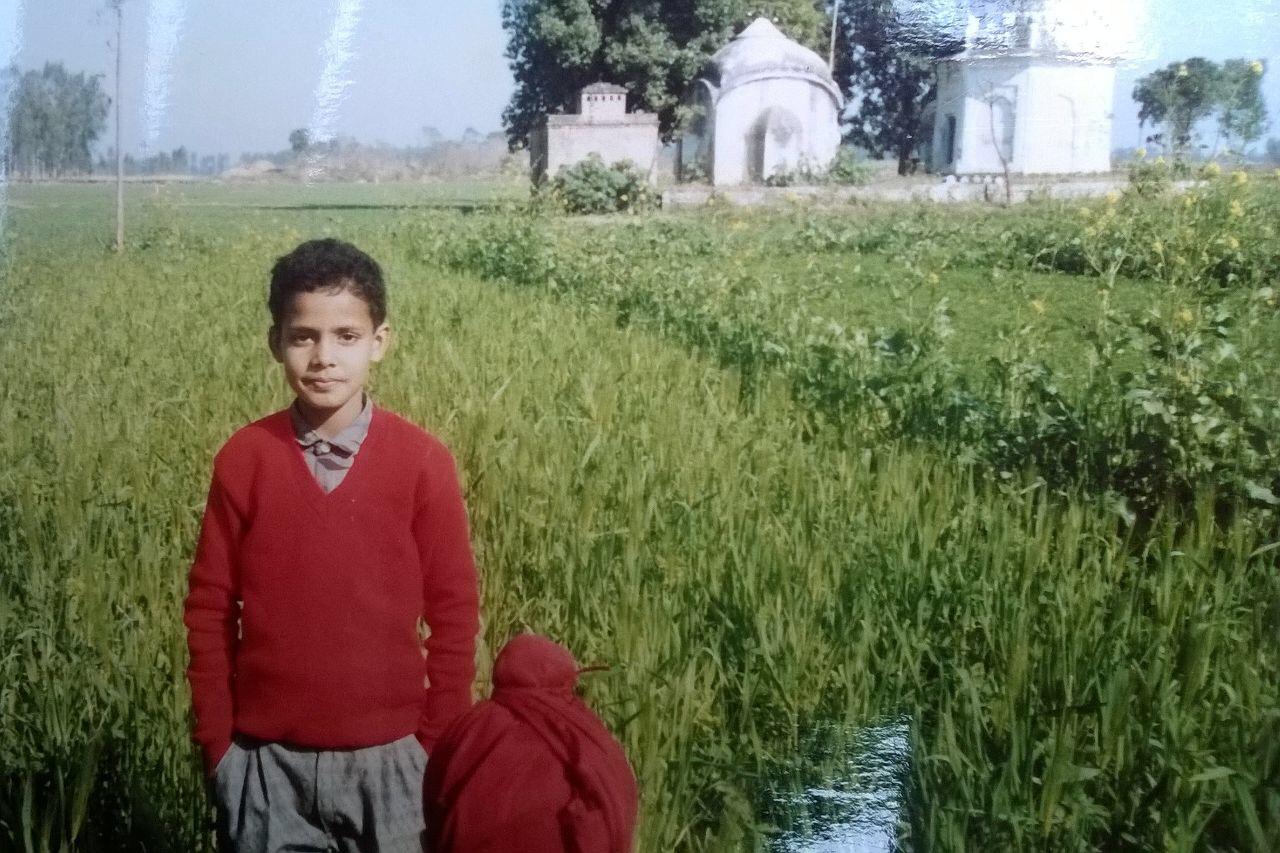

Born in Ghudani Kalan, a village in Punjab, Harminder says that while he was always inclined towards the arts, he was never a very bright student. “In hindsight, I can say that it does not matter, but it was tough when I was in school and was a below average performer,” he says. He describes himself as a “backbencher” when it concerned academics but was always the one to grab the first spot when it came to any art competition.

Despite being really good at art, not being academically sound attracted the ire of many and Harminder speaks about how he was often referred to as “trash”.

Recalling one such competition, he says, “When I was in class 7 there was a sculpture making competition and we were asked to make a sculpture from home and present it. I made a sculpture of Mahatma Buddha and that was the first time I saw my parents being proud of me.” Not being academically sound almost always invited the wrath of his family and teachers at school. It was looked upon as a sign of non-competency.

It was also around this time that Harminder had a paralytic attack, which left his right side completely paralysed and immobile.

“It took me close to three years to regain some of the strength in my right side and because of that I further deteriorated in my academics,” he says. Harminder would often hear people taunt and speak about what he would do in life given his physical condition. “The situation is so different today, schools are willing to look for aspects that children are good at other than academics. When I was growing up, I had no such luck,” he says.

Harminder speaks of the undue pressure put on him to excel in academics, and says, “It was not like I did not want to do well, but I could not study. That was not what I was meant to excel in. Looking back, I can say that it was difficult.”

“For all the hardships I encountered, my life now is filled with contentment.”

Despite having to live a rather difficult and turbulent childhood, there is not an ounce of anger or sense of defeat in Harminder’s voice. Instead he says, “I grew up in a time when academics was important. No one even thought that I could make a name for myself in the arts. I cannot blame anyone, all they were doing was look out for me.” He compares his life to that of an unpolished diamond, how it goes through severe hardships before actually being recognised as a worthy stone.

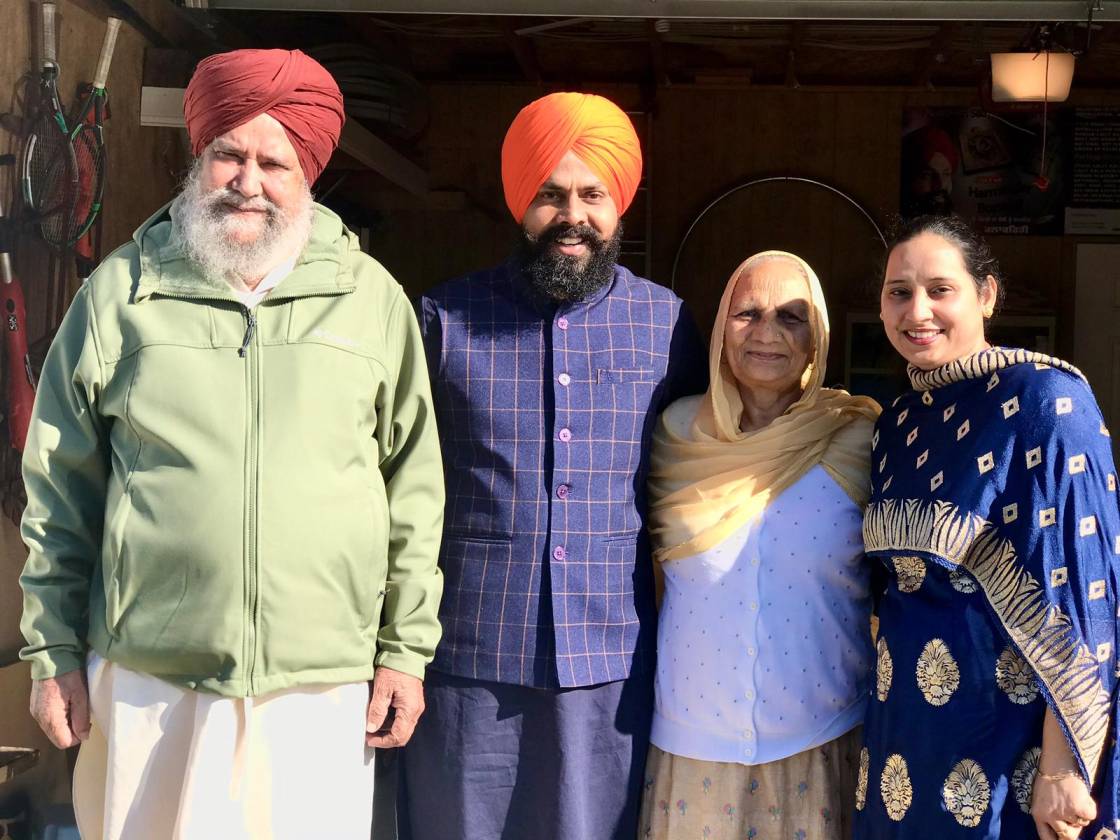

There are far too many hardships that Harminder says he encountered while growing up. From losing his older brother in the 90’s to having to work very hard to make ends meet as a family. “My parents had to worry about marrying off my five older sisters. I understand why they were sometimes hard and harsh on me,” he says.

It was during one of the classes that his teacher noticed Harminder sitting and drawing. It was his teacher, Manoneet Kalsi, who saw some potential in it and pushed him to participate in the college cultural festival. “That was the starting point for me. She took me to the arts department and literally started me off on my journey,” he says.

From Punjab to Michigan

From being unsure of participating in competition to winning the Gold Medal at the Zonal Clay Modelling Competition for three consecutive times from 2002, Harminder found his true calling in a Punjab college. From there he enrolled at TAC Academy of Fine Arts, Ludhiana in 2003 and pursued a two-year diploma in sculpture making. With time, his work started getting recognition and in 2007, his work was displayed at the India Academy of Fine Arts.

Yet another turning point in his life came in 2015 when he visited the US where his sisters were living. “I encountered a completely different way of life and learning in the US, and that has also contributed to shaping the person I am today,” he shares. In Punjab, where his initiation into the world of art started, he says, no one even knew what sculpting and clay modelling were. Whatever he learnt was on his own there.

A scholarship from the Holland Arts Council further helped Harminder grow as an artist.

Being at the centre he was able to display his work in countries like Germany, United Kingdom, Italy, and Brazil. He is also known for working with what is conventionally called ‘trash’ and turning them into pieces of art.

“I started by just picking up some discarded wooden golf clubs from a local scrap dealer, and found ways to turn them into art.

Scouting for scrap and visiting local garage sales became my thing,” he says with a hearty laugh.

From showcasing his work at the Van Singel Fine Arts Center in December 2016 to having participated in Art Prize 2017, which attracts more than 1500 artists from across the globe and domestically having bagged the Lalit Kala Punjab award and the National Art Ikon Award from HammerArt 2014, Harminder says he feels immense gratitude for all that has come his way.

While he is an artist par excellence, his grit and never-say-die attitude is also worthy of commendation.

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

No comments:

Post a Comment