Before there was Guy Fieri, Anthony Bordain and Julia Child, a young Indian Muslim immigrant changed the culinary landscape of America. Often deemed as America’s first celebrity chef, this boy, in his 20s, took the country by storm with his delectable curries, and incredibly good looks.

Ranji Smile—also referred to as Joe Ranji Smile or Prince Ranji Smile in some accounts—belonged to Karachi and arrived first in London in the late 1800s, where he worked for the Cecil Hotel, one of the largest hotels in Europe at the time. Here, he was spotted by Louis Sherry, a prominent restaurant owner, who ran Sherry’s in New York. Louis tried Ranji’s curry and immediately fell in love. He brought him, and his young English wife, to New York in 1899 to give American elites something new and “exotic” to swoon over.

In this day and age, Indian food may be a popular choice for take out food in America but when Ranji first arrived in the country at the dawn of the 20th century, things were different. America at the time knew of Indian food more through the eyes of Britain’s own interpretation of the cuisine, making the recipes twice removed from their original variants. The Brits defined curry as anything that was an amalgamation of onion, ginger, turmeric, garlic, pepper, chillies, coriander, cumin, and other spices cooked with shellfish, meat, or vegetables. These spices, before the American Revolution, were bought mainly via Britain. With the construction of the India Wharf in Boston in 1804, America could source these spices directly from India for the first time.

Despite that, American cooks lacked authenticity in the preparation of these curries, even as late as the 1880s. This changed when Ranji arrived in America.

‘Simmer, not boil’

The New York Letter described him as having “clear dark skin, brilliant black eyes, smooth black hair, and the whitest of teeth”, and noted how “women [were] going wild over him”. It seems like this was no secret to Ranji himself, who was quoted as saying, “If the women of America will but eat the food I prepare, they will be more beautiful than they as yet imagine. The eye will grow lustrous, the complexion will be yet so lovely, and the figure like unto those of our beautiful Indian women.”

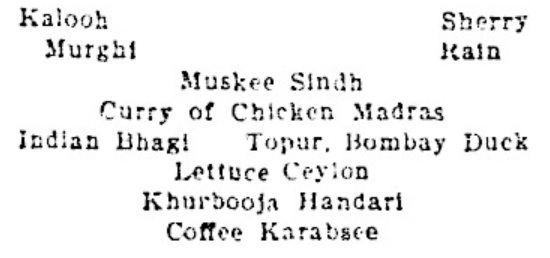

But what truly shook America were his delicious dishes, which were a stark contrast to the coloured water and mushy rice that the country had been consuming at the time. The items on his menu included the Kalooh Sherry, Murghi Rain, Muskee Sindh, Curry of Chicken Madras, Indian Bhagi Topur, Bombay Duck, or Lettuce Ceylon. Describing what it was like to eat Ranji’s food at Sherry’s, the New York Letter journalist said, “The fancy for curries…has taken possession of everyone who has eaten them. You take a seat at one of the dainty tables, look over the Indian menu with a sort of fear and trembling of what’s to come, with a delightful uncertainty pervading your soul.”

Ranji essayed the role of an alluring man from a foreign land extremely well. He would come out to serve the customers at Sherry’s dressed in traditional regal attire, spoke in a captivating accent, and introduced America to an authentic, yet poised version of Indian food. He would make a circle of a small portion of rice on the plate and place a small amount of chicken or curry in the middle, all the while telling his customers that Indian dishes were far from the spicy and peppery mesh Americans thought them to be. “Simmer, not boil,” he would say. He made his own curry powders and pastes, adding variations to suit the palates of the people he was serving, and said he followed no special rules for it — he cooked them up as and when the ideas popped up in his head.

A great showman

He said, “Oh, your great trouble in this country is the hurried cooking. I almost feel like fainting as I go to some of your great resorts, look into your kitchens, and see the way food is prepared. This gives me dyspepsia, which all my friends here whom I have served say they do not experience when eating of my curries.”

Ranji was not oblivious to his own prowess, and the effect he had on a country obsessed with ‘exoticism’ and ‘orientalism’. He attributed his good looks to the “careful way we eat in India”, which he promised to instruct American women on before he returned to his homeland. The New York Letter deconstructed the power he held in the kitchens of Sherry. He was given full autonomy and a separate space to work in the kitchen, with other chefs given strict orders to let him function independently.

Ranji toured the country to give cooking demos and classes in various department stores and food halls and offered cooking lessons to American housewives. In fact, he would continue to do so and be documented by America’s press for the next 15 years. With staggering ease, Ranji constructed a world of fables around himself, including that he was the fourth son of the Emir of Balochistan, a graduate of Cambridge University, and a friend of King Edward the VII. The American press viewed him as nothing short of royalty, and for years, Ranji effortlessly played the part.

The fame seemingly got to his head because he was arrested for drunk and disorderly conduct and broke federal laws when he brought 26 Indians with him to the US with a promise of providing them work. He told the press he had never claimed to be a prince, and that the 26 Indians were simply tourists. To the courts, he insisted he never promised employment to the workers, but that some were his friends, and maybe recruited to work in a restaurant he had been planning to start.

The King of Curry Cooks

What stands out here is that for years, Americans failed to notice that he was an undocumented immigrant. In 1904, Ranji went to the US Supreme Court to seek citizenship, before the citizenship tests existed. Although the country spent years idolizing the charming and talented “bad boy” of the culinary world, he was denied. At the time, the only law that dictated the immigration scenario was the Naturalisation Act of 1790, which stated that “free white persons…of good character” would be the only ones allowed to seek citizenship by naturalisation.

The Immigration Act of 1917, signed almost 104 years ago to the day, made it impossible for South Asians to gain entry into the US. Among them, was Ranji, whose hopes for becoming a US citizen were now completely squashed. Two months after the Act was signed, Ranji, like all other men of age in the country, was asked to fill out a draft application to fight in World War I — because South Asians were expected to endanger their lives for a country they were not even allowed to call their own. Ranji did not fight the war, and left for India with his newest wife, to open a new restaurant here. No accounts exist of such a restaurant, and Ranji’s story in history comes to an end. In the years he spent in the US, he came to be known as ‘The King of Curry Cooks’ and ‘America’s First Celebrity Chef’ across the country.

His story has since been chronicled by historians Sarah Lohman and Vivek Bald in a lecture held at the Brooklyn Historical Society. In fact, Lohman provides a precarious reconstruction of his life in her book Eight Flavours: The Untold Story of American Cuisine. In a review of her book in the New York Post, it is said that despite Ranji’s chaotic life in the US, he left an undeniable mark on the culinary landscape of the country. After Ranji left and immigration laws eased (even if ever so slightly), there was an influx of Indian immigrants, of which many opened Indian restaurants, inspired by Ranji’s culinary journey. One of them was Bombay Masala, one of the oldest and most renowned Indian restaurants in America.

Today, there are over 5,000 Indian restaurants in America. So the next time someone walks into one and samples a curry, here’s hoping they know of the dashing Indian who had his own hand in its making.

Edited by Yoshita Rao

No comments:

Post a Comment