As I congratulate India’s fourth-highest civilian award, the Padma Shri winner, for his exceptional contribution towards bringing global fame to the traditional art of Jamdani and Tangail sarees, a humble voice replies, ‘Thank you’. The 70-year-old weaver, Biren Kumar Basak, from West Bengal’s Phulia village is soft-spoken, and just like the Jamdani prints he weaves, he is humble and occasionally explodes with vibrancy.

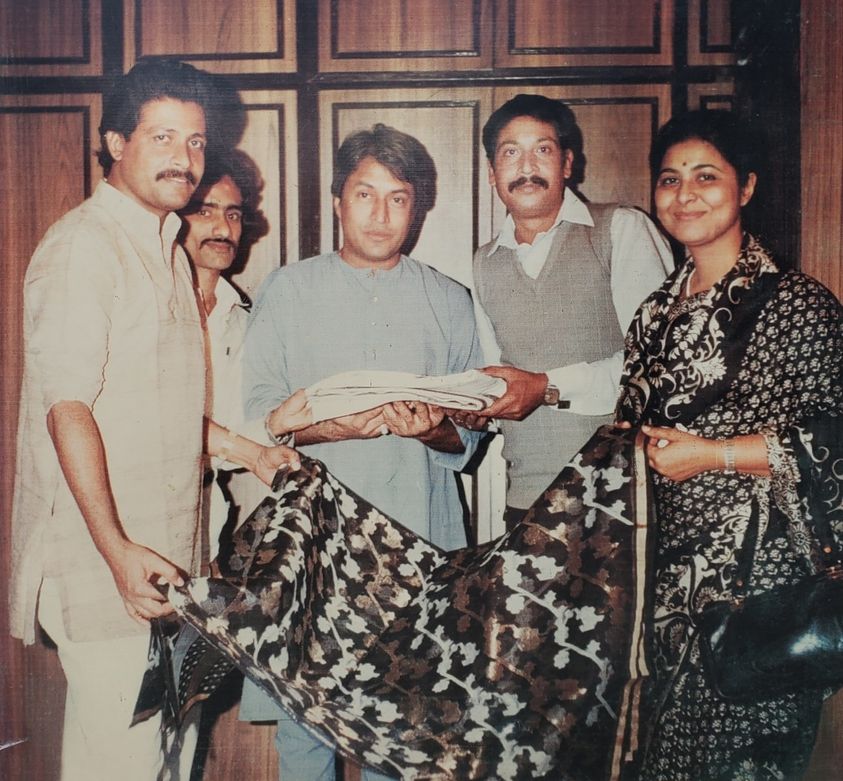

He has designed sarees for several well-known personalities — from Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee to the legendary director Satyajit Ray.

His skills and precision have bagged him several accolades including the Certificate of Merit (Ministry of Textiles, 2009), Sant Kabir Award (2013), Guinness Book of World Records for longest saree (2018), among others.

However, he never anticipated winning the Padma Shri. “I was speechless. I never fathomed such an honour would be given to a Bengali weaver like me and the numerous weavers associated with it,” Basak tells The Better India.

But he likes to treat all his credentials and awards as by-products of a superior goal — to preserve and continue the legacy of this beautiful art form by empowering thousands of local weavers. Basak then begins his story of how he came to own a 50-crore company that sells an average of two crore sarees every month.

Humble Beginnings

Originally from Tangail in East Pakistan, Basak was forced to migrate to Phulia in 1961 due to communal tensions. Since they came to India without any assets, their financial resources depleted swiftly. The dire circumstances didn’t allow him or his five other siblings to study as they took up odd jobs at weaving factories.

He spent his teenage years selling sarees door-to-door and worked his way up to build his own empire in the City of Joy.

Recalling his childhood, Basak says, “Communal riots began when I was in class 6. I still remember being terrified every time a crowd of people gathered in our neighbourhood. I didn’t understand much but knew that we weren’t safe there. Like many other families, we came to India as refugees.”

Surviving commanded priority over education. So, at the age of 13, Basak joined his father, Banko Bihari Basak, at a local saree weaving unit earning Rs 2.5 per day in 1964. His father was a master weaver of Tangail and Jamdani saree, and hailing from a generational weaver’s family, it was a skill junior Basak learnt swiftly.

Basak worked at the unit from 1962 to 1972 after which he started selling sarees in Kolkata with his brother, Dhiren Basak. “We would leave home in Phulia at 5 am and take a local train to Kolkata. There, we would spend the entire day selling sarees door-to-door. Then take the last train back to Phulia. My father would wait for us at the station holding a hurricane light as we’d reach late.”

Their routine was set. However, Basak saw no tangible growth until after a few months when he accidentally met a minister’s wife in a handicraft store. Seeing the two dejected and exhausted brothers, the lady asked them to visit her at home with more sarees.

“The next day we went to her house only to find a crowd of women waiting to buy our sarees. We made a great sale that day. She made sure that her entire network of women knew about us and opened us to a huge world of clientele. From army wives, intellectuals, to bureaucrats, we were selling sarees to many high-profile people. One of them was a High Court judge, Padma Khastgir,” adds Basak.

The selling price per saree gradually increased from Rs 10 to Rs 100. The duo saved enough to purchase a place in Southern Park and established Dhiren and Biren Basak and Company in 1985.

Mastering the Craft

In 1987, Basak parted ways with his brother and returned to Phulia with a hope to financially empower local weavers and provide them with a platform that he never had.

He started Biren Basak and Company with eight staff members in his house and trained them in Tangail and Jamdani weaving style. Alongside he rigorously practised and evolved his own skills. He innovated his own designs and experimented with challenging techniques.

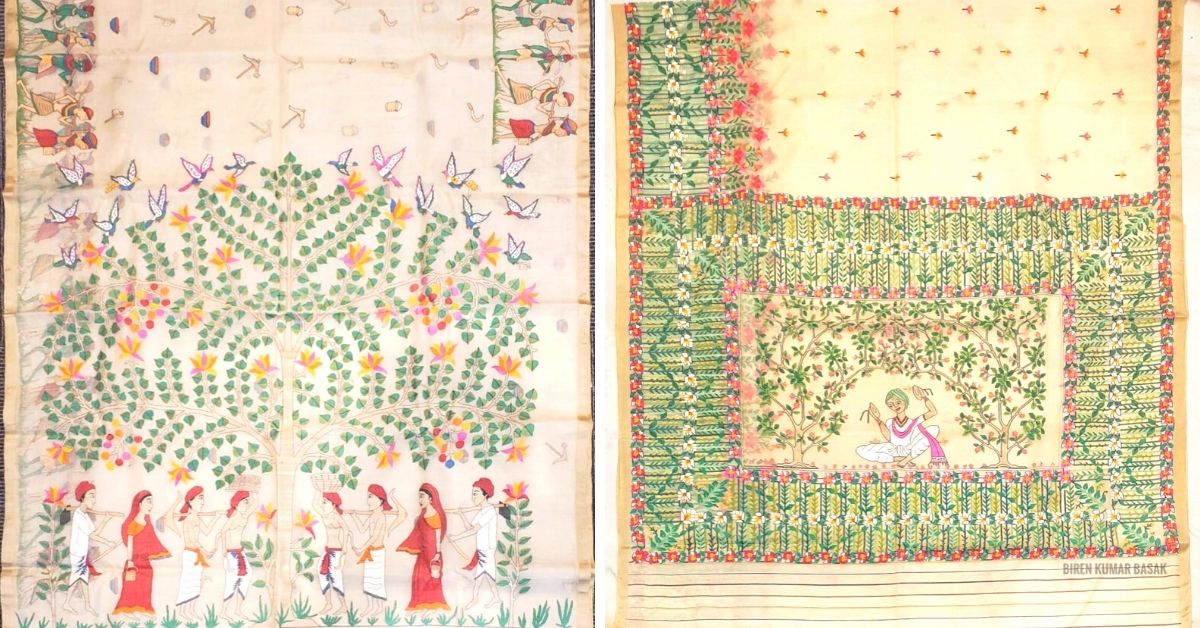

Defined by intricately hand-woven rich motifs, Jamdani is a weft technique of weaving. By virtue of its intricate design, it is considered to be an advanced and challenging hand-weaving technique. The process is time-consuming and each saree can take up to a year.

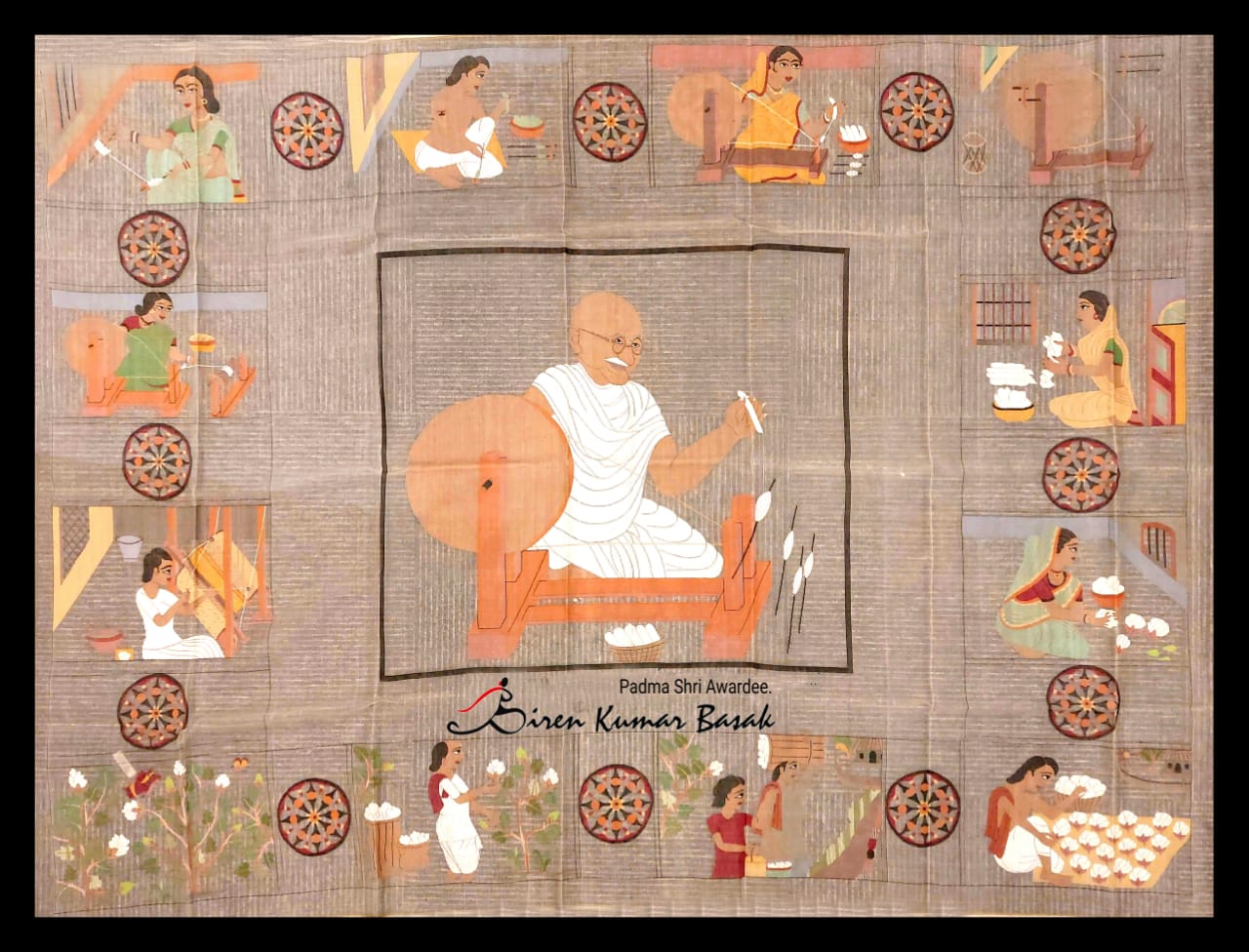

Case in point is the Ramayana saree for which he secured a place in the Limca Book of Records. It took him nearly 2.5 years to weave the first Dhakai saree with embroidery designs depicting the Ramayana Epic. Likewise, he took over a year to weave a saree that contained 1.25 lakh words.

Other sarees have designs and patterns that are woven with traditional Bengali and Indian motifs or are based on Hindu mythological themes such as Lord Krishna, Lord Ganesha. His collection also includes illustrious people of India and creating unique pieces of art on tant fabrics, which have become his trademark. Tangail sarees are similar to Jamdani. They have figured motifs in a transparent backdrop with extra warp on the borders.

Basak can weave sarees from various materials like cotton, silk, mulberry or non-mulberry, and khadi muslin. “From a Rs 200 saree to one costing in lakhs, which is made of pure gold, I have made it all and hope to weave a stronger legacy for Bengali weaver community in the future,” he says and adds, “Presently, I am working with 5,000 artisans to make them self-reliant.”

His timely delivery, exceptional craftsmanship and artistic knowledge have garnered him clients from all over the world along with prominent Indian personalities such as singer Lata Mangeshkar, cricketer Sourav Ganguly, noted classical musician Ustad Amjad Ali Khan, among others.

The awards and a prestigious clientele even landed him calls from big designers; however, he prefers collaboration over simply selling them the sarees. He says, “I have always been open to working with big names in the fashion industry. It is always a pleasure to see my work being appreciated by more people. But, I cannot support the trend where big designers buy sarees from us for the right price and then sell it with minor changes for almost ten times the original price.”

Asked what is his secret recipe behind establishing a successful empire, Basak says, “I have no set strategy per se. You see, I still don’t see myself as a businessman, but a mere artist. I believe the money will run after you if you manage to stay true to your work and focus on achieving success through quality.”

Starting as a weaver on a meagre income to creating his own business, and from being a door-to-door salesman to customers lining up outside his store in Phulia, Basak has certainly come a long way.

Edited by Yoshita Rao

No comments:

Post a Comment