If the phrase ‘in record time’ holds true for anything, it’s for the race to develop the COVID-19 vaccine. This is an effort that countries across the world have unanimously worked for in the last year since the pandemic wreaked havoc in our lives. The National Geographic said that a vaccine typically takes 10-15 years to reach the public. But vaccines to combat the coronavirus have come through faster than any other we’ve seen in history so far.

Right now, India has approved two vaccines for emergency use — Serum Institute’s Covishield and Bharat Biotech’s Covaxin. Recently, Health Minister Harsh Vardhan said that India may see more vaccines being approved for emergency use in the next few months. Moreover, the Serum Institute of India said it will ship the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine to Canada in less than a month after a conversation between the prime ministers of the two countries ensued earlier this week.

However, this association between the two countries is age-old. India and Canada have stood by each for decades now, despite a recent kink when Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau supported the ongoing farmer agitation in the country.

A brief history

Decades ago, in the aftermath of the Partition of India, when the country was distraught with bloodshed and the displacement of millions, India reached out to Canada for doses of penicillin for a campaign against Malaria. But to understand why this exchange took place, a brief context of India’s state in terms of vaccine development needs to be first understood.

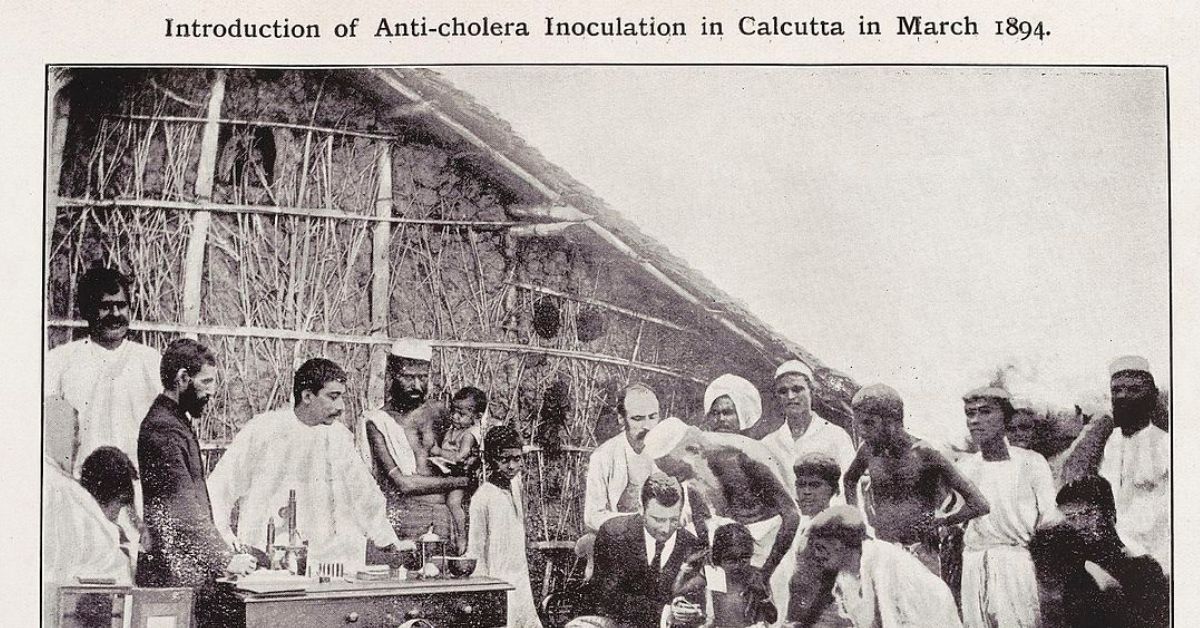

In the 19th century, Ukrainian biologist Dr Waldemar Haffkine introduced India to the cholera vaccine, which he had developed while studying in Paris. The British Raj at the time asked him to stay back and develop a vaccine for the plague afflicting the country in 1896. A year later, Haffkine had invented the first vaccine for the plague, which arguably became the first vaccine to be developed in India.

In his paper, A Brief History of Vaccines and Vaccinations in India, Chandrakant Lahariya wrote that towards the beginning of the 20th century, socio-scientific-geopolitical events had a heavy impact on vaccination efforts in the country. Some of these changes included the First World War, which took precedence for the government, despite it coinciding with the Influenza Pandemic. Most significant among these, Lahariya says, was the Government Act of 1919, which delegated administrative powers from the Centre to the provinces. This included these local self-governments to be assigned the responsibility of providing healthcare, including the smallpox vaccine. Lahariya says that while this act was introduced with good intentions, local governments had limited financial capacity to fund vaccinators. By 1939, when World War II began, vaccination efforts further became a casualty.

The Print quoted Dr Madhavi Yenappu, principal scientist at the New Delhi-based National Institute of Science Technology and Development Studies, saying that up until the 1930s, India was doing well in terms of vaccine research and development, but after two world wars, these institutions were left obsolete, despite having the expertise.

Across borders

The result of the Partition, as we know now, was mass communal violence and displacement of millions. Around 20 million people were displaced across religious lines, giving birth to an alarming refugee crisis. A health crisis was naturally looming. According to this report, India suffered from 75 million cases of malaria, and 8,00,000 deaths were directly attributed to the disease. The population of the country in 1947 was around 344 million, which implied that the annual rate of incidence was a whopping 22%.

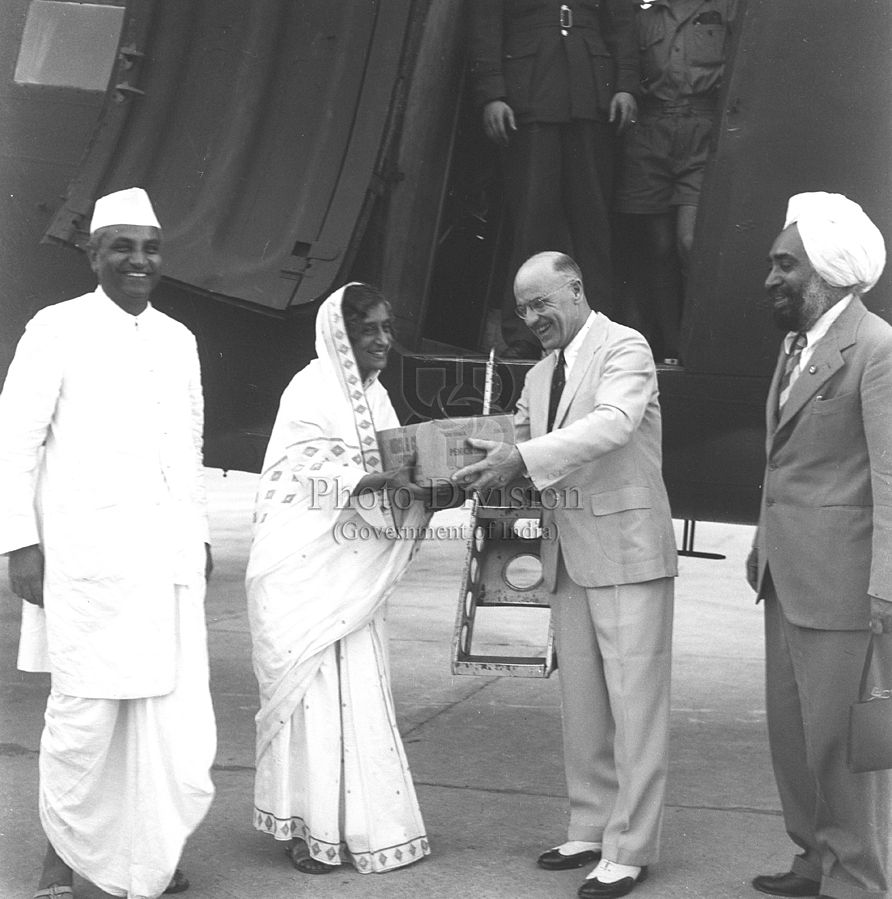

Concerned over the casualties owing to this historic bifurcation of the subcontinent, the Canadian Red Cross donated penicillin to its sister organisations in India. The plane carrying 139 cases of penicillin arrived first at Pakistan’s Karachi, where it off-loaded 47 cases, and then flew down to New Delhi to deliver 92 cases. The doses were received on October 17, 1947, by then Health Minister Rajkumari Amrit Kaur, alongside Dr Jivraj Mehta, Director General of Health Services, and Sardar Balwant Singh Puri of the Indian Red Cross.

After independence, the Indian government increased funding for research and development to the private sector. The BCG vaccine laboratory also came up, and vaccination for tuberculosis was expanded over the years through government initiatives. By 1955-56, all the States of the Indian Union were covered under the government’s mass campaign.

Around 1967-68, India also reformulated its strategy to eradicate smallpox, by focussing on surveillance, epidemiological investigation of outbreaks, and through massive containment drives. By 1971, the vaccine uptake had increased significantly, and in 1975, the country reported its last case of smallpox. In 1978, the Expanded Immunisation Programme was launched by the Indian government, which introduced vaccines for TB, polio, and tetanus. Arriving at economic liberalisation in the 90s, Yenappu says the private sector was incentivized to produce vaccines, which gave further boost in its mass manufacturing.

The Serum Institute of India, established in 1966 by Cyrus Poonwalla, was one of the first private companies to begin manufacturing a vaccine for measles in India. The country’s pharma industry saw exponential change owing to liberalisation. With a combination of rapid indigenous expansion and overseas collaboration, Indian pharma companies invested immensely to become global players.

Today, almost 74 years later since receiving the 92 doses of penicillin, India is returning the gesture made in 1947. In a tweet on February 15, Adar Poonawalla, CEO of the Serum Institute of India, said regulatory approvals from Canada are being awaited to ship doses of the Covishield vaccine within a month. According to Hindustan Times, around 5 lakh doses were agreed to be sent to Canada in a conversation held between Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. Apart from Canada, India has sent COVID-19 vaccines to nations including the Maldives, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Myanmar.

There’s nothing like a devastating health crisis to shake any country’s foundation to its core, and the coronavirus pandemic has been proof of that. But what cannot be ignored is how countries across the world come together to fight it. For a country that houses the world’s largest manufacturer of vaccines, India has certainly not shied away from proving true the phrase ‘What are friends for?’

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

No comments:

Post a Comment