Malegaon ka Superman was released a decade ago.

The film had no special effects, glamorous sets, superstars, smart gadgetry, mind blowing stunts or any filmmaking aesthetics. The movie was never part of Hindi cinema’s prolific industry, nor did it ever desire to be, and yet, eminent directors like Zoya Akhtar and Anurag Kashyap were spotted in the front row, thoroughly enjoying the special screening in 2011.

The movie, made on a shoe-string budget by Nasir Shaikh, is a desi version of Hollywood’s Superman. The superhero’s mission is to save Malegaon, Maharashtra’s textile hub, from a tobacco-loving villain.

In a cruel twist of fate, Shafique Shaikh, who played the lead, was addicted to tobacco and succumbed to mouth cancer six hours after the film screening. He was merely 25-years-old and is survived by his wife and two young daughters.

“Malegaon is a special place and Shafiq was a special person. He was in a bad shape, he just kept staring at us, he had an oxygen tube, couldn’t talk,” Kashyap told Mid-Day in 2011.

“An ardent fan of Amitabh Bachchan and Bollywood action movies, Shafique watched the film on a stretcher. Although he was unable to speak, he was thrilled to see over 2,000 people thoroughly enjoying his performance and frequently bursting out in laughter. We were glad to fulfil his dying wish, and I am sure he is flying high, wherever he is,” Nasir tells The Better India.

While Nasir was making the film, documentary filmmaker Faiza Ahmed Khan was shooting the crew behind the scenes. Titled ‘Supermen of Malegaon’, the fascinating one-hour homage follows a bunch of amateur filmmakers (who have full-time jobs by the day) capturing the true essence of the small city, which is about 300 kilometres north of Mumbai.

When Khan learnt about this unheard film industry called Mollywood (in line with Hollywood) making ridiculously low-budget film cum spoofs of big-budget movies, she visited Malegaon with a potential documentary idea. At the time, Nasir had just begun shooting Malegaon Ka Superman.

“(The films) were a labour of love, and not just made for money. It was a community endeavour — everyone seemed to participate in some way. Technical hurdles were overcome by the most astonishing improvisations,” Khan recalled in a 2012-interview with The Indian Express.

Interestingly, the documentary became an instant hit and won several awards at film festivals, including Asiatica Film Mediale in Rome, Indian Film Festival of Los Angeles (IFFLA) and Karachi film festival.

The movie and documentary came out a decade ago, so why am I writing about it now?

A few days ago, a friend of mine was gushing (or rather, reminiscing) over the movie that I had no idea of, despite being up-to-date on all pop-culture nostalgia references. After some blasphemous taunting from my friend, I quickly googled, watched the documentary and immediately kicked myself for missing out on a legendary story.

So for those who are unaware, fret not, as we trace the history of people who refused to be bogged down by budget constraints, expertise and aesthetics. For them, all that mattered was entertaining the audience and fulfilling their passions.

Malegaon Ka Superman

You know your film is an all-out entertaining one when Mr Perfectionist himself lauds you. “Saw Malegaon Ka Superman some time back. What a fantastic film! Really loved it! I believe it has released today. Go for it,” actor Aamir Khan told IANS post the film’s release.

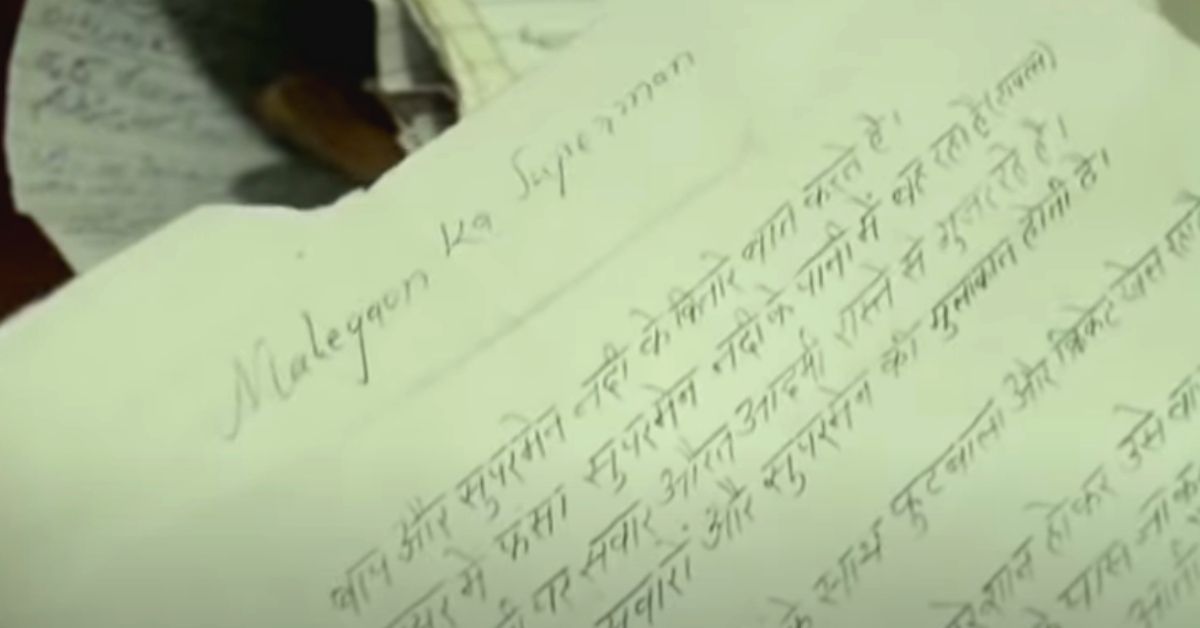

When Nasir was writing the film in his 100-page notebook, all he wanted to do was highlight local social and civic issues, by engaging with Superman. In many ways, he tried to make the film as realistic as possible. The biggest testimony is the hero, Shafique, who neither had 6-pack abs nor an intriguing voice. He was a thin chap with a soft voice. By choosing him, Nasir shattered the quintessential image of a hero and affirmed that Superman is one among us.

Superman udega toh pura Malegaon udega (If superman flies, the entire Malegaon will also fly) — with this moving tagline, Nasir began filming. He made his own green chroma (or as locally pronounced ‘Karoma’). To meet expenses, he even included subtle ad placements. A local milk centre gave around Rs 10,000 for brand placement.

Malegaon’s Superman is accident prone, scared to jump in the lake, falls in sewage while stopping a truck, and gets electrocuted while climbing a pole. In the trailer, you can see him floating down the river on a tire and fighting gutka barons. He wears a blue suit, red cape, rubber chappel and Bermuda shorts, and a visible naada (strongs to tie the shorts) as a comic element.

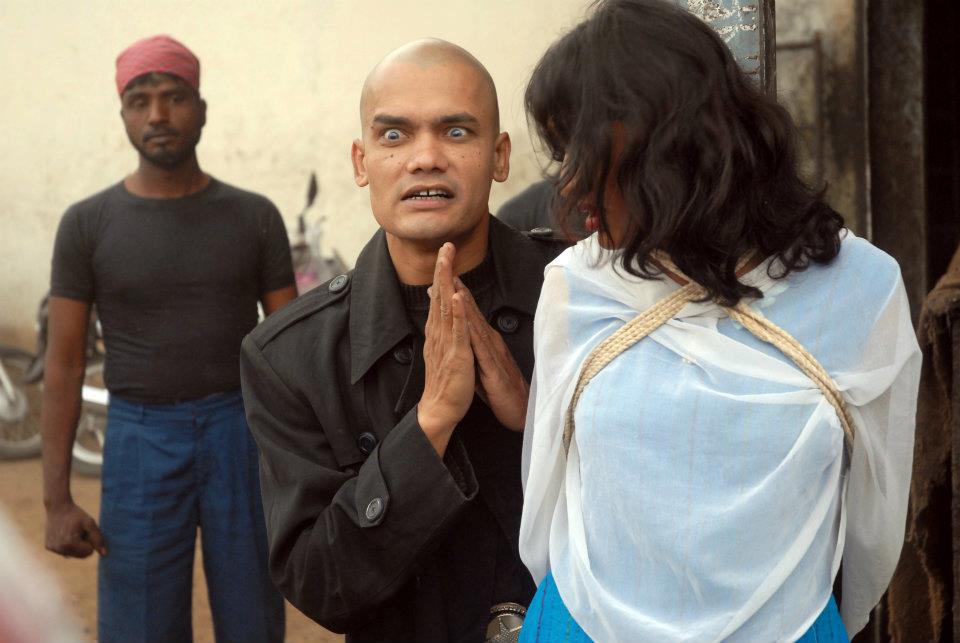

Meanwhile, the villain is a typical bald man, dressed in black clothes and with an evil laughter. “I want to see every person, old, young, women, men, children, spitting gutka on pavements. I like dirt,” he reiterates throughout the film.

The shooting process was an amalgamation of innovation and jugad. In Khan’s documentary, high-tension cables have been replaced with poles attached alongside the green chroma wall. Superman sleeps on the pole and with hands suspended in the air. The crew uses cardboards to fan Superman so his cape and hair fly dramatically. For crane shots, they have used bullock carts and motorbikes for tracking shots.

Needless to say, after doing goofy things throughout the film, the climax scene involved rescuing his lady love from the clutches of the antagonist.

Ronit Jadhav, an independent filmmaker from Mumbai, aptly sums the spirit of Malegaon ka Superman and says, “I remember watching this film in college. The sheer, genuine passion with which the makers were preparing for the film is what has remained with me still. This wasn’t a big-budget studio flick with stars and item numbers; this was just a bunch of villagers utilising their ingenuity to its maximum potential. This was passion-driven jugad, which was more honest and real than most box office hits.”

A product of pure & sincere love for cinema

Malegaon, a town in Nasik district, is infamous for its 2006 bomb blasts, which shook the city’s spirit and uprooted hundreds of lives. Once a settlement of migrant weavers, the town has numerous power loom factories that make grey cloth worth Rs 45 crore daily. Thousands of families, including Shafique’s, earn a livelihood from the factories.

Amid power cuts and 8-9 hours of laborious work, the traditionally conservative settlement found its solace in movies. It is a typical case of escaping from under the veil of depression and grim reality for a couple of hours, says Nasir, “Once you enter the theatre, you can feel like the hero. It’s almost as if Bollywood actors have taken efforts solely to entertain the people of Malegaon.”

Nasir’s fascination with cinema is slightly different. He once owned a video parlour where he would mostly screen English movies. His first stint with filmmaking came with cutting scenes with dialogues from these movies, and retaining the action scenes. Subtitles were not a thing at the time.

During screenings, Nasir would closely observe the camera angles, lighting, background music and screenplay. He treated every movie as his guru and learnt whatever he could. He received his first creative validation through movie posters. He would draw and paint posters of the movies he had seen after understanding the plot. People loved the posters and his audiences increased.

Finally, in early 2000, Nasir borrowed Rs 50,000 from his brother and made his first spoof film — Malegaon ka Sholay. He shot it on a Handycam and edited it on VCR. He screened the film in his parlour, and it ran for over two months generating a profit of Rs 2,00,000.

Of course, it was nowhere close to a proper film. It had shaky footage, a sound lag, and poor writing. Yet, people rushed to purchase tickets in black, for it was the first time someone had made a film on them. Their city, their people and the local dialect was in the movie. This was the triggering point of what would be an emotional moviemaking journey.

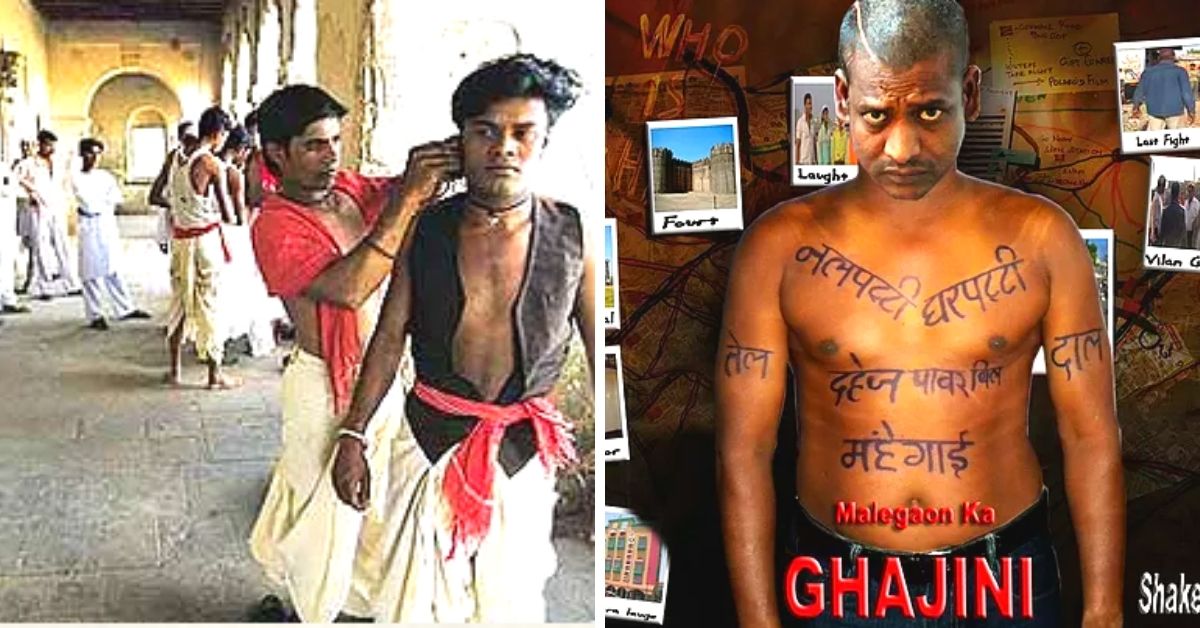

Next came the spoof of Ashutosh Gowarikar’s Oscar-nominated film, Lagaan. It was made by Farogh Jafri, who ran a tile-polishing business. Jafri borrowed Rs 30,000 from a well-to-do man on the condition that the latter’s son would be cast as the main lead in Malegaon Ki Lagaan. Then came, Malegaon ki Shaan, Malegaon ka Don, Malegaon ka Ghajini and so on. Close to ten production houses sprang up.

These films were made with minuscule budgets and wedding videographers doubled as a cinematographer. Nasir mentions how sometimes actors wouldn’t turn up due to job commitments, cameras would spoil in between and power cuts stalled the schedules.

Low budgets meant not paying enough (in some cases, not paying at all) to the actors and the rest of the crew. It was almost like every film came with a disclaimer that roughly translated to, “You won’t be paid, but will get free food.”

Despite these issues, the community continued making movies. It didn’t matter that they were a laughing stock or that their movies tanked (though, rarely). Their passion, motivation and indomitable spirit made up for the lack of knowledge and expertise.

Some of them even received new opportunities from Mumbai. Nasir went on to direct a 26-episode series called ‘Malegaon ka Chintu’ that streamed on Sony Pal between 2010 and 2014. Meanwhile, the villain of the series bagged a pivotal role in a Marathi film.

However, the Mollywood industry shut in 2015, thanks to an influx of entertainment options including OTT. Everyone parted ways, some went back to their job and some ventured into new arenas. Nasir now runs a hotel in the city.

‘To what extent are you willing to go to fulfil your dream?’ is a question that cannot possibly have a measurable answer. But Malegaon and its people make for a perfect answer. They are just a bunch of movie fanatics, who came together, had fun on sets, created a hilariously memorable product, and translated their dream into reality.

Watch Supermen of Malegaon here:

Edited by Divya Sethu

No comments:

Post a Comment