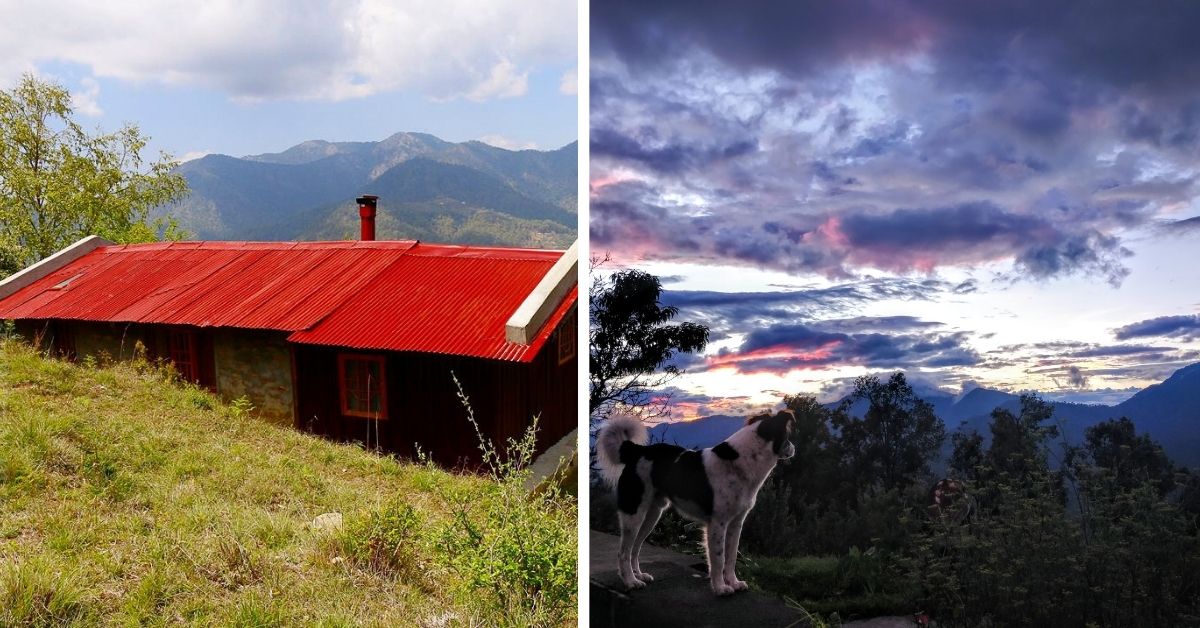

At 78, Steve Lall is as exuberant as one could be. As I connect with him via a short video call, I’m greeted by a vibrant smile and a booming, “Hello!” But our call is cut short by a rocky internet connection that day, for Lall lives with his wife, Parvati, in the quiet foothills of the Himalayas among the Kumaon ranges in Uttarakhand. He owns and resides in the Jilling Estate, which he has spent decades protecting and preserving. Since the 70s, Lall has worked to rebuild and protect the ecosystem of the 140-acre estate land. The estate consists of agricultural land and orchards, interspersed with rhododendron, oak, chestnut, apricot and pine trees and is surrounded by forests.

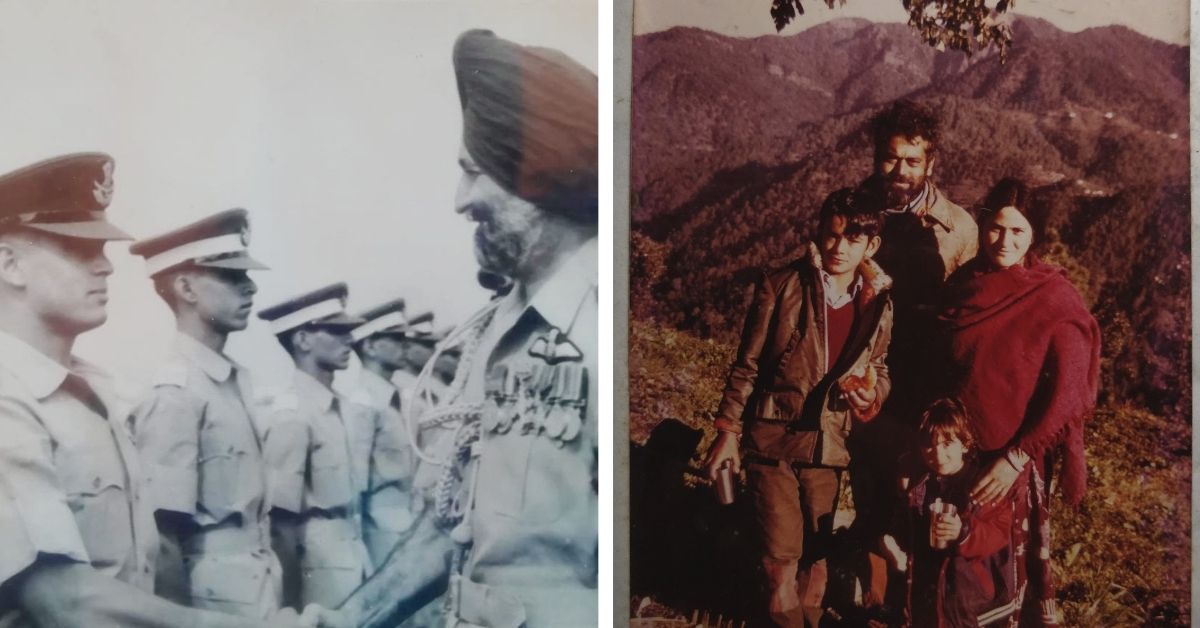

“My father was in the Indian Civil Services in the UP cadre, and I was born in Banaras (now Varanasi). For five years, we were in Gangtok, Sikkim, when my father J S Lall was sent there by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru to be the Dewan of Sikkim, from 1949-1954. From there we lived in different parts of the country like Jhansi, Agra, Bareilly and Delhi. Our family moved around a lot of forests, so I developed an attachment to nature quite early in my life,” he tells The Better India.

Destructive commercialisation

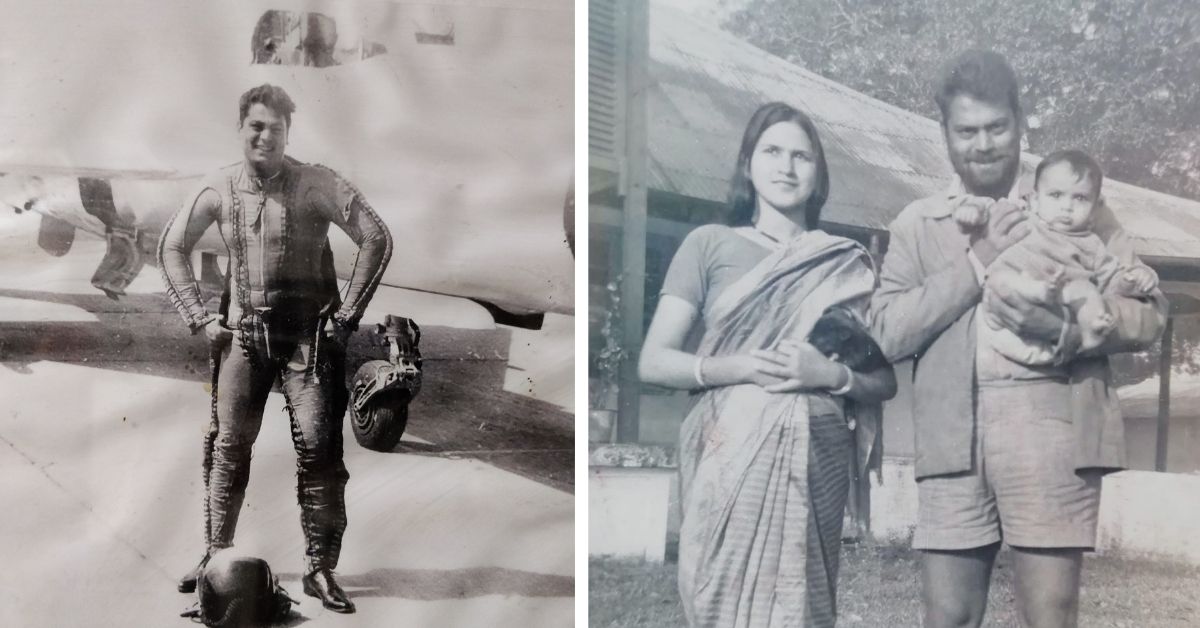

Since he was 6, Lall desired to be a fighter pilot. He spent a decade in the Indian Air Force and returned to Jilling to run his family estate. “My mother, Hope Violet Lall, purchased it in 1965,” he says. She bought it from a man who was given the land by the Government of India sometime after the Partition. Before this, the estate belonged to a British family, the Stiffles, who owned the land in the early 1900s. At the time, it was called Jilung. Over time, the expanse, covering orchards, forests, and farmlands, came to be known as Jeeling, and now belongs to the Lall family. Today, it’s known as Jilling, or Jilling Estate, as named by the Lalls.

“I used to come back here when I was on leave from the Air Force, and ramble around in the area. After I quit the airforce and returned for good, I met my wife, Parvati, and we fell in love,” he says. Parvati was native to the area, and her father had served in the Kumaon regiment during World War II. For Lall, this shift from a life of combat to one amid isolated mountains was not a dramatic one. He reiterates his affection for nature and says the shift was simply a continuation of what he had always loved.

Kumaon had been struggling, and its destruction began slowly, says Lall. “The surrounding areas outside our boundary began taking a beating when outsiders started lopping trees to build their own dream homes,” he recalls. “The area also began experiencing a shortage of fodder. Locals would then come to our boundaries to chop off a few branches or leaves to feed their cattle and for firewood, for which I don’t blame them.” Moreover, water sources were drying, and the locals were slipping further down the slope of poverty.

Lall hadn’t returned with too many savings in hand. With Parvati by his side, he tried his hands at farming and selling produce but still lived hand-to-mouth. “It became a labour of love — we weren’t earning too much money,” he says. To make a better livelihood, the Lalls began hosting guests at their estate. “People from various embassies, travellers from abroad, among others, would come and stay with us. My daughter, Nandini, and I would take them out on treks,” he recalls. “We did small things here and there to keep ourselves afloat, but I’ve been more or less of a chowkidar,” he quips.

Many battles, every day

With the expanse of his estate, Lall could very well be a “multi-crore chap”, as he says, through commercial tourism and by building a massive resort. Instead, he never hosted more than five to six couples at a time and kept the whole operation low-key and low-density. This ensured that destruction in his area due to booming tourism was prevented. “I’ve got nothing in the bank, but have plenty else,” he laughs.

“The Stiffles had maintained a fruit orchard on this land,” Lall says, adding, “By the time they left, there were many vacant areas where I later tried to replant and maintain the orchard. But I eventually realised the best way was to look after the boundaries, ensure there’s no damage in the area, and nature herself would take care of the rest.” This chowkidari bore fruit when oak, chestnut, rhododendron, among others, began growing slowly in the area in and around the estate. In about 30-odd years, Lall says, the forests have thickened multifold. This also saw the growth of flora and fauna that was native to the area. “We were not taking crops from outside and planting them here. The ecosystem remained pure,” he adds.

The Lalls battle forest fires and the devil’s weed to sustain their land. “Climate change has meant that our surroundings are getting drier, especially when it doesn’t snow. Forest fires start in the winters itself,” Nandini, Lall’s daughter, tells The Better India. “When it rains, we take care of the small gullies to see where the water is flowing, to prevent landslides,” she adds.

That a man of Lall’s background chose to turn his back on a thriving life in the city to grow a forest was absurd to his friends. Visits to him were infrequent, because of the steep climb that must be completed before arriving at Jilling. “But the new Indian is different,” Lall says of the enthusiasm that the younger generation has to explore. “Things have changed a lot since 40-50 years ago. Initially, my guests would only be people from embassies or foreigners but now more than 90% of our visitors are Indians.”

Now that tourists are enjoying a spot like Jilling, the Lalls are approached by many who want to buy land in the area to build a home. “Everyone wants a house in the mountains,” Nandini says, adding, “But they also want the luxuries of a city life. Striking a balance is hard.”

“At first, it was just about keeping locals at bay. Now, we’ve got multimillionaires and affluent people in our neighbourhood buying up large tracts of land, who want to make it a posh city-like township. They want to make mansions and helipads.” Lall says. He adds, “We remain fearless and shall continue doing what we do.”

Alongside, Parvati has been fighting to keep kaala jhaad, also known as the devil’s weed, which is an aggressive type of weed, from threatening to destroy the ecosystem the Lalls have slowly spent time building. It arrived here a few years ago and has spread quite fast. In particular, horses in the area have been dying owing to a respiratory disease that is caused by ingesting the weed.

Guardian of the hills

When it comes to essaying the role of a chowkidar, Lall says he’s done many things to keep intruders out of Jilling, including chasing them down the small paths of the hills. “I scared the hell out of them,” he laughs. “See, they (the intruders) are all our own people at the end of the day. If I were poor and without my own resources, I would also be looking at other ways to protect myself and earn a living. But our family is respected in the area. I don’t strut around and behave like a bully. The idea is that you approach the better side of the people, and hopefully, they respond the same. This has worked all these years,” he says.

In 2014, Lall’s estate was covered by English writer and adventurer Ben Fogle for the second season of the show, Ben Fogle: New Lives in the Wild. The show covered various people around the world who have left behind a thriving life in the city to find happiness in the countryside.

But is a quiet life in the hills boring? “Never,” Lall says. “I have a multitude of interests that keep me occupied.” These include Lall’s favourite motorcycle, which he has used to travel to various parts of the country to visit his friends. These bike rides had to take a backseat after Lall got into an accident a few years ago. Regardless, he engages in reading, playing instruments, engaging with guests in the estate, and in other activities, and says he is never bored, never lonely.

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Lall and his wife were cut off from their extended family and friends for quite some time, and tourism prospects further decreased. But not a hint of bitterness can be found in his voice. Lall is a man of his convictions, and has not strayed from the cause he felt so strongly for, ever since he was a child. Today, Jilling — lush, green, and thriving — stands as a result of the dedicated efforts of one family.

Edited by Yoshita Rao

No comments:

Post a Comment