In April 1950, Makhan Singh, a native of Punjab and a trade union leader fighting for the cause of Kenyan independence against the British, did something quite revolutionary. During a meeting in Nairobi between the Kenyan African National Union (KANU), the first ruling political party following their independence in 1963, and the East African Indian National Congress, a political party representing Indian/Asian interests in Kenya, Makhan Singh stood up to speak to his comrades sitting there.

In an impassioned address, he demanded ‘Uhuru Sasa’, which in Kiswahili meant ‘Freedom Now’. This was the first-ever call for total Kenyan independence from Britain.

Yes, you heard that right. A bespectacled Punjabi man spoke up in Nairobi and called for the British to grant total independence to their colony. British authorities soon arrested Makhan for being an “undesirable person” under its Deportation (Immigrant British Subjects) Ordinance of 1949. This arrest was inevitable given the fact that prior to this proclamation he was organising boycotts and strikes against British interests in Kenya.

In a show of defiance, he said that his actions were “justified in the circumstances”.

For the next 11 years, he was moved from one prison to another, and not permitted any visitors except close family members. Barely a few years after his release, Kenya declared its independence from the British on 12 December 1963.

Before his speech in 1950, however, he also participated in the Indian freedom struggle before moving back to his adopted country. It’s a story not enough people know.

An Indian Taken to Kenya

Born on 27 December 1913, in the village of Gharjakh, Gujranwala district, which is today in the Pakistani side of Punjab, he was only six years old when his father left for Kenya to work for the railways like many Punjabis of his time. By the time Makhan turned 14, his father took the family along, which included his mother and sister, to Kenya.

However, by the time Makhan had moved to Kenya, his father began running a printing press on the side. A brilliant student, Makhan started helping out his father in the printing press after his exams to support the family.

“There he learned more about the exploitation of workers and colonial injustices and met with members of the Ghadr [also written as Ghadar] Party, an ally of India’s Communist Party,” noted this 2009 article published in The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest.

It wasn’t long before he organised a strike against the printing industry, which now included his own father who had given him a job. Before dwelling further into his work, it’s imperative to understand the context within which Indians operated in Kenya.

Breaking the Colour Barrier

As this 1971 column titled ‘The Lost Indians of Kenya’ for The New York Review noted:

In the preceding seventy years [before the 1960s], more than a quarter-million of them [Indians] had been encouraged by Britain to settle in the East African colonies. Most of these Indians were traders, artisans, or lower professionals, occupying the middle position between black and white in the colonial hierarchy. They lived in their own large communities, segregated from both the Africans and the English. They were the essential instrument of British rule over the indigenous population, and had greater contact with the Africans than did the British. As such, they received more privilege than was granted the Africans, but by the same token they earned a lot more of the black resentment than the colonists did.

Probably Makhan’s greatest achievement was breaking the colour barrier and uniting the Indian and African population into challenging the British.

In 1934, one of the earliest trade unions was created in Kenya called the Indian Trade Union, of which Makhan was elected its secretary in March 1935.

Unhappy with the name and its narrow appeal, he lobbied nearly 500 of his fellow trade unionists to change the organisation’s name to the Labour Trade Union of Kenya (LTUK), which was open to members from all races. In fact, the LTUK began publishing its handouts in Punjabi, Gujarati, Urdu and Kiswahili as well. His objective was to attract as wide an audience as possible to the cause among the more oppressed community groups.

“Successful strikes on behalf of railway workers and those in other industries followed and the union grew to also include members in neighbouring Uganda and Tanganyika (present-day Tanzania). The Indian Trade Union, which had been renamed the Labour Trade Union of Kenya, was now the Labour Trade Union of East Africa (LTUEA),” noted an article in Scroll.in by Arko Dasgupta, a PhD student in History at Carnegie Mellon University.

Despite organising and generating all this momentum, Makhan had kept an eye on events in his homeland. What followed was that in December 1939, he visited India to “study working-class conditions and functioning of Trade Unionism in Bombay and Ahmedabad”. However, his stint in India wasn’t to be uneventful.

He met and addressed mass meetings on labour strikers in then Bombay, and even attended the Indian National Congress session in Ramgarh as an African delegate.

Fearing that his anti-colonial sensibilities could further cause them trouble, the British kept bouncing him around from one prison to another for two years. Post-release, his movements were restricted to his native village in Gujranwala for another two and a half years.

The British finally released him in January 1945. Without wasting any further time, he found work as a sub-editor for Jang-i-Azadi, a revolutionary weekly.

Understanding the inevitability of independence for India and the potential for extreme violence during Partition, he came back to Kenya in early 1947. As soon as he landed in Nairobi, the authorities sought to deport him for the workers’ campaigns he had organised during the 1930s. Despite all their experience, the British believed that “in the circumstances of Kenya today, it [was] unlikely that a non-African, however fanatical, would emerge as a leader capable of stirring up the masses”. They let him go, and that was a mistake.

“He was elected vice-president of the Kenya Youth League in December 1947 and undertook a Gandhian hunger strike in June 1948 to protest post-partition communalism in Nairobi,” noted Gerard McCann for the Journal of Social History.

Throughout this time in Kenya, he advocated Indians working closely with their African counterparts and pushed his fellow Punjabis and Gujaratis in Kenya to learn Swahili, which he called “the language of the people”.

Towards Freedom For All

Fast forward to his arrest in 1950, and two years later, Kenya witnessed the famous Mau Mau Uprising/Rebellion led by Kenya Land and Freedom Army (KLFA), a guerrilla army comprising recruits of central and eastern Kenya, which also resisted the British. In this brutal uprising which lasted for nearly a decade, about 11,000 Mau Mau and other rebels were killed. The British themselves executed about 1,090 convicts, while only 32 white settlers were killed.

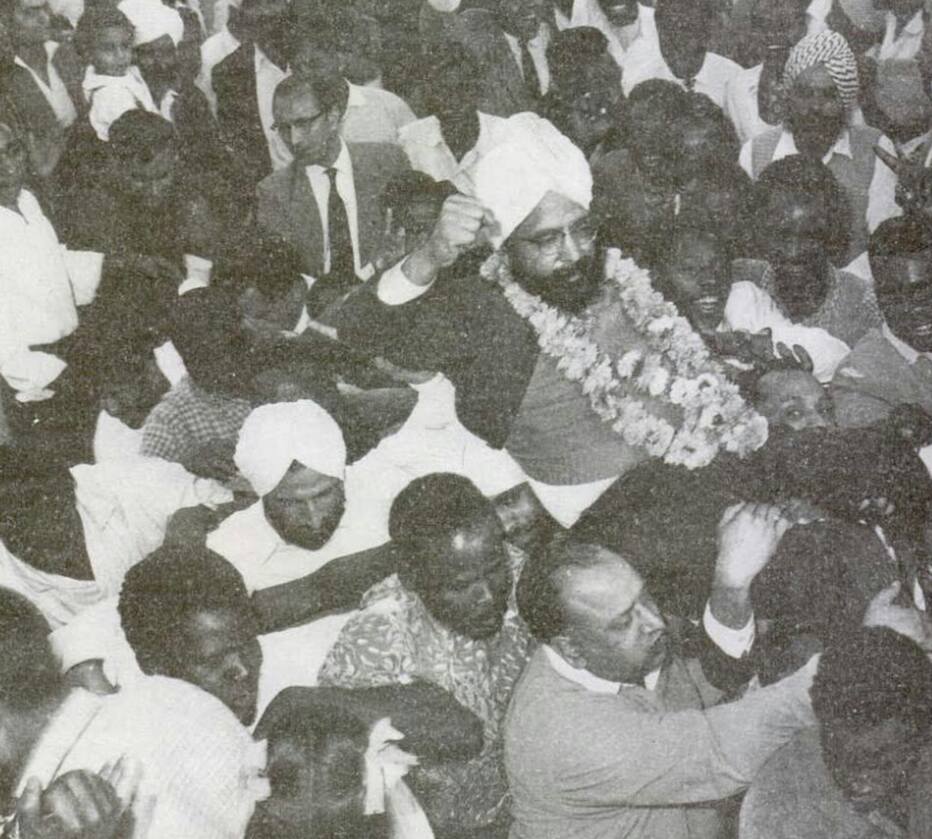

Kenya was in a state of total emergency until 1961. Meanwhile, Makhan was released in 1961 following the colonial government’s decision to lift restrictions since Kenya was no longer under a state of Emergency. Upon his release, his politics did not waver and continued to advocate for trade unions.

“Moreover, he aired his support for Jomo Kenyatta, who would go on to become independent Kenya’s first head of government. Before freedom arrived in 1963, Singh joined Kenyatta’s Kenya African National Union once membership became open to all races. Shortly after, he was granted permanent residency in the country,” noted the Scroll.in article.

Despite all his work, when independence did come, he wasn’t invited to join the government. Moreover, the East African Indian National Congress, who had changed their name to the Kenya India Congress (KIC), was dissolved in 1962 because they felt the party was “no longer desirable to function politically as an Asian organisation”.

He eventually slipped away from the political limelight and by 1973, he died at the Aga Khan Hospital in Nairobi following a heart attack. But the legacy he leaves behind is unquestionable.

Besides lending a major hand in both nationalist movements, particularly in Kenya, Makhan believed that the pursuit of freedom and justice is not restricted by your country of birth.

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

No comments:

Post a Comment