Who laid the foundations of modern Indian journalism? This is a tough question to answer because our freedom struggle witnessed the emergence of so many fine publications run by editors of the highest calibre.

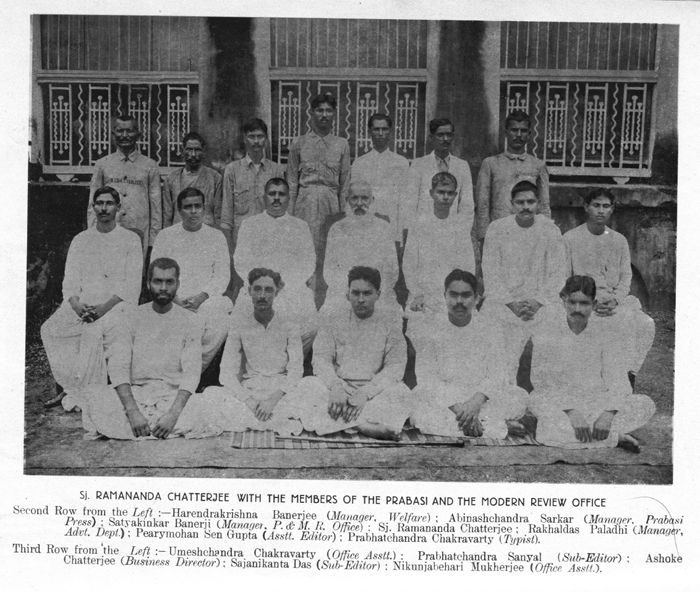

(Image above courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

However, one would be hard pressed to find one as influential and respected as Ramananda Chatterjee, who founded and edited two journals called The Modern Review (in English) and Prabasi (in Bengali). No publication, one could argue, would command the respect and influence opinion across undivided India more than the ones Ramananda started.

Backed by the freedom struggle’s call for total independence from the British and spirit of social reform, his journals welcomed stalwart contributors of different ideologies, who freely articulated their understanding of India’s past, present and immediate future. These contributors included Rabindranath Tagore, MK Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Subhash Chandra Bose, Verrier Elwin, Sister Nivedita, Premchand, Jadunath Sarkar, CF Andrews and even Lala Lajpat Rai.

As Gopal Haldar, a Bengali scholar wrote in 1965, for the Indian Literature journal: “Under his masterly guidance, the periodicals became shining lights of Indian journalism and a tower of strength in the cause of Indian struggle. Rightly it may be claimed that he who achieved this, achieved for his people something imperishable — an inspiration for cultural pursuits and moral strivings and a faith in their capacity for objective thinking and solid work.”

Personally, he was a classic liberal and an ardent nationalist at the same time.

Although his publications laid great emphasis on accurate facts and figures, his life’s mission was to witness the end of British rule and the moral repugnancy that came with it.

The Becomings of a Newsman

Born into a family of very modest means on 12 May 1865 in Pathakpara village of Bankura district, Bengal, Ramananda witnessed tragedy very early in his life when his father passed away as a young teenager.

With his family struggling to make ends meet following the death of his father, a young Ramananda made his way through the world on the back of his immense intellectual abilities and personal integrity.

Winning one scholarship after another, he paid for his own education all the way to post graduation and even used some of that money to support his family. In 1888, after finishing top of the class in his BA examination, while studying in Calcutta University, he earned the Ripon Scholarship for higher studies in the United Kingdom.

But he refused a scholarship that would have guaranteed him a well-paying career. This is because he was a member of the Brahmo Samaj, an influential socio-religious reform movement. “For, he had before him the example of Brahmo stalwarts like Sivanath Sastri, and would not serve the foreign Government that ruled the country. He decided to maintain himself and his dependents at home in Bankura by taking up a lecturer’s job on a modest salary of Rs 100 at the City College, Calcutta,” Gopal Haldar wrote in his 1965 article for Indian Literature.

In addition to the lecturer’s job, he also found writing gigs with different journals to supplement his income, and in 1890 was offered the job of an assistant editor at the Indian Messenger, a Brahmo Samaj run publication.

His stint there set him up for a career in journalism. In 1895, Ramananda left Calcutta and made his way to Allahabad, where he was posted as the principal of the Kayastha Pathshala (college) there. He continued his journalistic endeavours by becoming the editor of a Bengali publication called Pradip, where his talents really shone through.

Influencing Thought and Opinion in Modern India

During his tenure as principal, he launched Prabasi (which meant Non-Resident Bengali), a Bengali journal in April 1901. It was a success within the first three years of its launch. “By the early 1920s, the journal’s circulation was around 7,500, a feat considering the low literacy rates of the time. From its first issue, Tagore was one of its main contributors, an association that continued for 40 years,” noted this article in Live History India.

“If for nothing else, a periodical which had the honour of presenting first to the public the major creative works of Tagore in prose and verse for 40 eventful years…The Prabasi remains the biggest treasure house for Tagore studies and researches,” Gopal Haldar noted.

In addition to Tagore, however, the editor also enlisted other artists, intellectuals and scientists of the time including JC Bose, PC Ray, artist Abanindranath Tagore, historian Jadunath Sarkar and scholars like Jogesh Chandra Ray. The spirit stoked by publications like Parabasi is what drove epochal moments like the Swadeshi Movement (1904-07) and hastened the rest of India into touching their freedom nerve. By 1906, he resigned as principal of Kayastha Pathshala and dedicated all his energy to journalism.

In January 1907, Ramananda launched The Modern Review, a month after the annual session of the Indian National Congress which adopted the resolution of self government (Swaraj) as a goal for all Indians. It was a goal that Ramananda believed in as well and his publication reflected that spirit. Fearing the impact of his words, local authorities in present day Uttar Pradesh drove him out of Allahabad and he came to Calcutta the following year.

“The Modern Review addressed itself to the intelligentsia of this multilingual country and to progressive men and women of the English reading world. It drew its contributors from the thinkers and intellectuals from all parts of the globe, and sought to interpret India, her glory and her misery–and her struggle against that misery–to humanity at large. It was a difficult task; and, on a proper estimate, it will be seen that no one except Tagore and Gandhi could win so respectful and so responsible a hearing for India at the bare of humanity as this magazine’s editor,” noted Gopal Haldar.

As an editor, Ramananda performed this yeoman service for 35 years straight.

According to historian Jadunath Sarkar, “It became the voice of India to the world outside, and he was heard with attention in every country where reason and humanity were honoured by its thinkers.”

Both publications had a segment called ‘Notes’ in The Modern Review and ‘Vividha Prasanga’ in Prabasi which fearlessly challenged the validity of British rule and called upon Indians to rise up against. But this didn’t mean that stalwarts of the Indian freedom movement like Gandhi, Nehru or Bose were exempt from criticism as well.

He even courted arrest on charges of sedition in 1928 for publishing a book titled ‘India in Bondage: Her Right To Be Free’ by an American author called Jabez T Sunderland. According to this article in Live History India, he lost the case and paid a fine of Rs 2,500 (equivalent to Rs 5 lakh today). In addition to politics, these publications also played a fundamental role in promoting the cause of Indian Art as well.

A standout feature of his publications was his strong adherence to liberalism. For example, according to Dileep Padgaonkar, the former editor of the Times of India, Ramananda “insisted on publishing the educational or professional achievements of all Indian women in his two magazines, with the photographs of the heroines”.

“However, it is precisely Ramananda Chatterjee’s relentless espousal of progressive causes with a steady moral compass to guide him that accounts for the rich legacy he bequeathed to later generations of journalists. His was no narrow nationalism. He bore not the slightest taint of caste or communal prejudice. He was wholly committed to democracy and to an equitable social and economic order,” added Dileep Padgaonkar.

He also launched Vishal Bharat (1928) in Hindi for readers in the Hindi heartland and the Indian diaspora in the Caribbean, South and East Africa and Fiji Islands. However, this didn’t take off like his previous two publications. Such was the respect he had garnered that the League of Nations (precursor to the United Nations) invited him to their session in Geneva to hear India’s case in 1927. But Ramananda himself wasn’t best pleased about what took place at the session.

He wrote in The Modern Review edition of November 1927: “So far as India’s desire and efforts for political emancipation are concerned, the League of Nations would be of as much help to her (India) as a college debating society.”

Till his last breath on 30 September 1943, Ramananda continued publishing his journals and staunchly pushing the cause of Indian Independence. Sadly, he wasn’t alive to see his dream of a free India come true, but what he did was lay the foundation of modern Indian journalism.

Despite recent events, there are journalists who continue to espouse his values.

That, one could argue, is reason enough to celebrate his legacy.

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

No comments:

Post a Comment