Discourse around sexual wellness in India remains tiptoed around, hushed up, avoided, or ignored. A report in the Reproductive Health Journal states that in India, young women, especially those in rural areas, are at a high risk of negative sexual and reproductive health (SRH) outcomes. Women aged between 15 and 24 years constitute 41% of the total maternal deaths in the country. This, and more, stems from a lack of understanding of sexual wellness in the country. For laws and legislations to work, a deep correlation with awareness and understanding of sexual health and wellness must exist, and vice versa.

In one of the country’s first steps towards initiating a conversation around this topic, 75 village women in Ajmer district in Rajasthan came together in 1989 to write a book named Shareer Ki Jankaari (About the Body). This initiative was part of the Central government’s Women’s Development Programme in Rajasthan, which began in 1984 aimed to build awareness among rural women based on case studies through group formations. The programme was launched across six districts and at the time stood out for its direct participation of women.

What power does a woman hold over her body?

The women conceptualised and designed Shareer Ki Jankaari with the help of activists Malika Virdi, Indira Pancholi and a few doctors. Over a period of about two years, they all met regularly to slowly build the book. It was part of a year-long health programme developed under WDP, says Pancholi.

“The genesis of the book was simple,” Virdi tells The Better India. “Women from different districts of Rajasthan wanted to address fertility control. But fertility cannot be spoken about without a larger understanding of women’s sexuality and basic physiology. That’s how we worked on Shareer Ki Jankaari.”

“We worked with these women, who were called saathins, to figure out the issues women face with respect to their bodies. This included how we’re built, how much control we have over our bodies and contraception. It wasn’t just biology classes that we were organising. The objective was to collectively understand the emotions and agency women attach with their own bodies and sexuality,” she says.

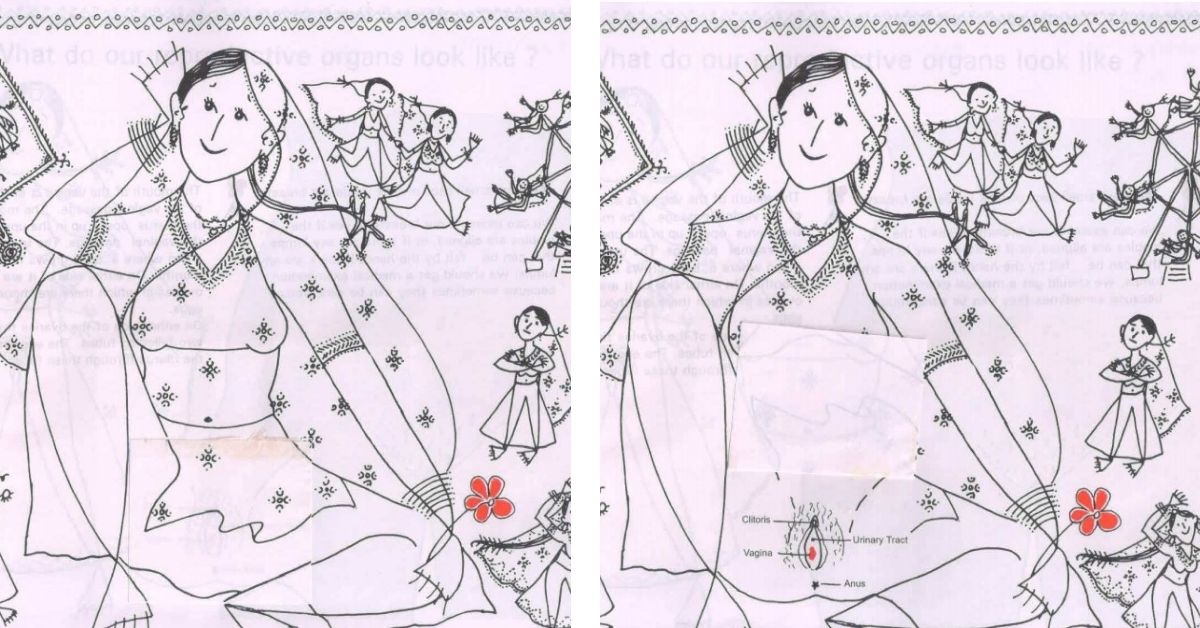

“I was around 21 years old when I joined the project,” Pancholi says, adding, “At the time, I was already involved with WDP. The first draft of the book was made by referencing science and medical books and how they addressed women’s sexuality. We put photos of body parts and marked them the way you’d find in science books, but the women were a little scandalised by naked bodies and felt that they would not be able to show them around in their villages. They asked us to put ghagras and odanis on them. They also wanted it to be in their language.”

Virdi adds, “The challenge was that all these women belonged to villages, and we were talking about vigyan (science) and satta (power). So we held a series of workshops over a year with them to help deepen the understanding of both.” The idea was to weave a linear and structured scientific method of giving information around contraception with the non-linear and interconnected art of visual storytelling.

Labour of love

Pancholi says these women offered their inputs in terms of the language they wanted the book to be in and how they maintained their menstrual calendars. To remember information discussed in the workshops, they would make up songs, which were also incorporated in the book. They discussed how they count the days they are fertile, how they kept a record of their menstrual cycle, and topics including the process of childbirth. “The discussions were very open,” Pancholi recalls. “They discussed the nature of their white discharge in different phases of fertility, and talked about sexual urges at different points in the cycle.”

She adds that Virdi played an important role in designing and ideating how the book would be presented to readers. Since she had years of experience in the field of education, her inputs helped shape how the book would inform readers who were not literate.

Bardi Bai (69), one of the women involved in the project, was 37 when the book was being made. In a remote village in Ajmer, Bardi was a labourer in the field where a three-day workshop was held to discuss the book. They had set up a temporary home in which she and her two kids lived. Her husband was no more.

“Many of the women were dais (traditional birth attendants), who had a good understanding of women’s bodies and the process of childbirth. So we wanted to highlight those aspects in the book as well. The response from the village was good, but the government didn’t want us to carry it forward because they found the book to be graphic and vulgar. That’s why we incorporated flaps, which would cover the body parts, and could be lifted to see the structure. Before the book, we did not possess any knowledge about our own bodies, how it worked, and what control we had over it. Shareer Ki Jankaari helped us gain better understanding,” says Bardi Bai, who eventually became the panchayat sarpanch at her village, a saathin with the project and a social worker.

Virdi says, “The process of making the book itself was very creative and educational, because discussions were centered around how we perceive our bodies. They were variously represented by the women through their drawing. These multitude of viewpoints were then tied together in the final book as a narrative closest to their visual language. But by the time the book was printed, the scenario had changed completely. We were asked to leave the project along with the saathins, we took a stand against the coercive state population control measures of the time. Besides, the book threatened patriarchal mindsets and the charge here was that it was “promoting indecency”.”

She adds, “Around 1987, the target of government employees was to meet targets of the sterilising people as part of the Famine Relief Works. We felt that here we’re talking about empowering people with jankaari, but the larger question was, ‘Do we just stop there?’ The sterilisation process had to be monitored in terms of whether guidelines and safety protocols were being followed. We were accused of going against the national programme of population control. But our point was that the agency has to be with the women — they themselves should get to take a call about whether they want to have more kids or not.”

By the time the book was complete, Virdi and her colleagues had been asked to leave the project. Moreover, because of the pictures depicted in the book, the team had been asked by government officials to not publish it. “Representatives of the government recalled all the copies we had distributed and burned them,” Pancholi says.

Virdi and Pancholi took up a small working space to finish the book themselves, but the neighbours would often think they were sitting together to discuss “vulgar” topics. “The area we were working in was very small, so anything you would do, other residents would know. It took us 15-20 days to give the book its final shape,” says Pancholi.

The activists and village women took this final book to Kali for Women, which was India’s first feminist publishing house. Kali was started by Urvashi Butalia and Ritu Menon in 1984 with an aim to bring women to the forefront through academic publishing. So this manuscript fit right into their scheme of doing things. “Us taking the book to a feminist publishing house ensured that it would see the light of day,” says Virdi.

Transcending boundaries of an urban city

“A few women from the group came to our office one afternoon with hand-made copies of the book,” Butalia tells The Better India. “They told us that the community had protested at the time because the book showed naked bodies, which they said was unrealistic because you never see a naked woman in the village.”

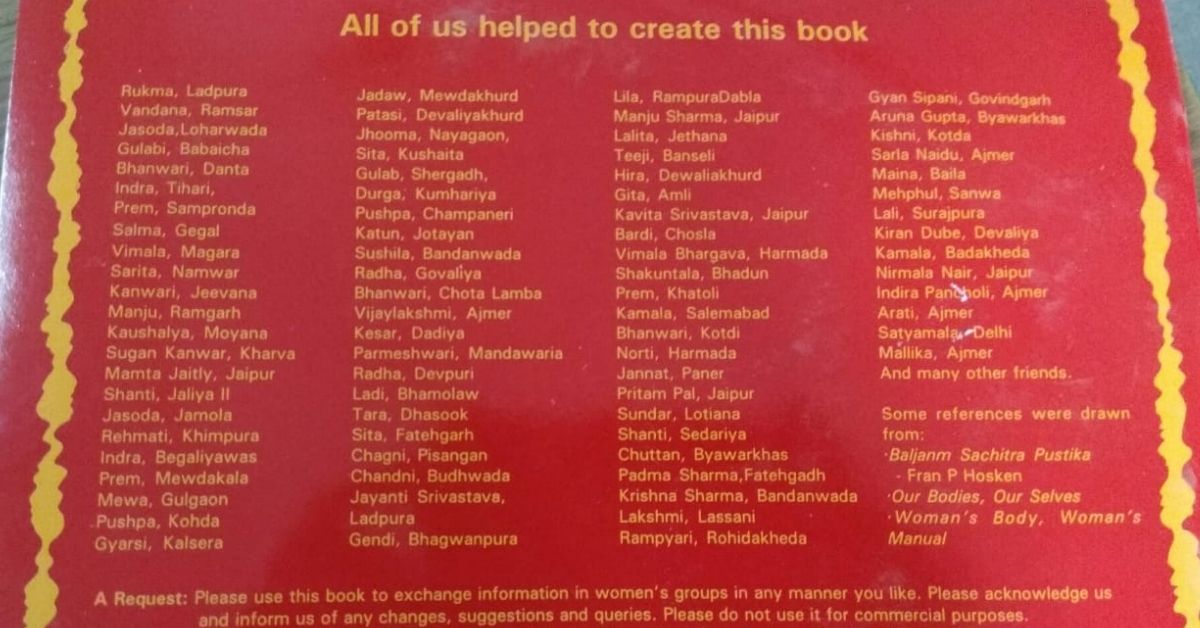

She further adds, “They told us about the book’s history and that they want us to publish it. Their only condition was that we would not sell it for a profit to any village woman who wanted a copy. They also said they wanted all 75 names on the cover. We were more than happy with the conditions, because as feminist publishers, it’s not every day that you get to work on a book that transcends the boundaries of an urban city and language. Kali was based in Delhi and we used to publish in English, and here was a book written exclusively by village women in Hindi.”

The publishing process itself was intricate. “Publishing back then wasn’t as advanced as it is today. All the binding of the books were done by hand, in an old city called Ballimaran. The process was carried out by young boys in the locality. So when the book went from our printers to the binders, we were told that the young boys aren’t being able to work because they were so in awe of the book. So we started looking for women binders. There was a group called Action India which worked in slums at the time to train women to do binding. So we got in touch with them and they took on the task.”

Kali started by printing 2,000 copies of the book, priced at Rs 12 each. However, the village women worked so hard to sell their copies that before Kali finished printing, 1,800 copies had already been pre-sold. “The book was also pirated a lot and printed in various different languages such Gujarati, Marathi, Kannada and Tamil,” she says. “We had sold somewhere between 75,000-80,000 copies up until four to five years ago.” Not a single copy was sold through a bookstore. Instead, it was sold through various women’s groups, individuals, and agencies, among others.

But the book is not just for children. Virdi emphasises, “It’s for women. The book covers various grounds — it talks about menstruation, white discharge (and which is healthy and which is not), even touches upon men’s sexuality, old age, menopause, and fertility cycle, among many other topics.” The book closes with all the names of all the women who contributed, with the message that it is “an effort to recognise [the women’s] own power”.

Karuna Phillip is a social worker at Mahila Jan Adhikar Samiti, which works to help victims of violence. She says, “We still use this book, because a lot of our work revolves around health and nutrition, as well as adolescence. It is very simple to understand and interpret, which helps us reach out to the rural community, especially young brides, who don’t have much knowledge of their own bodies. This book can be understood regardless of whether someone is literate, because of its pictures and the way it’s been made. The women we work with connect with its ‘rural touch’.”

The samiti uses the book in training programmes and workshops to discuss maternal and sexual health. “The women sit with their mothers-in-laws or sisters-in-laws and discuss the content of the book and their own understanding of it,” Phillip says.

Perhaps today, Shareer Ki Jankaari is far simpler when one puts it in the context of how the discourse around sexuality has evolved. However, back then, the book was the first to pioneer the conversation of self-hood and women’s agency over their own bodies. It breaks the barriers of the echo chamber in which we discuss our bodies, with the aim to empower those who exist in the fringes of society. The English translation of one of the songs inside goes, “We have power, we have the strength to create…A world of my own, where my spirits soar free”.

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

No comments:

Post a Comment