On 6 August 2001, the Moideen Badusha Mental Home in Erwadi village, Tamil Nadu, caught fire. The origins of the fire remain unknown, but 45 patients housed in the facility perished. This was because they had been chained to their beds—despite it being forbidden by law to do so by authorities—so chances of escaping were minimal. Some whose shackles were not as tight managed to escape — five were treated for severe burns, and some remain missing.

Patients at this facility, like many others in the village at the time, were regularly caned to “drive the evil away”, and were instructed to await a “divine command” that would let them know that they were cured to return home. For some, this command would come within months, and for others, it would take several years, or possibly never.

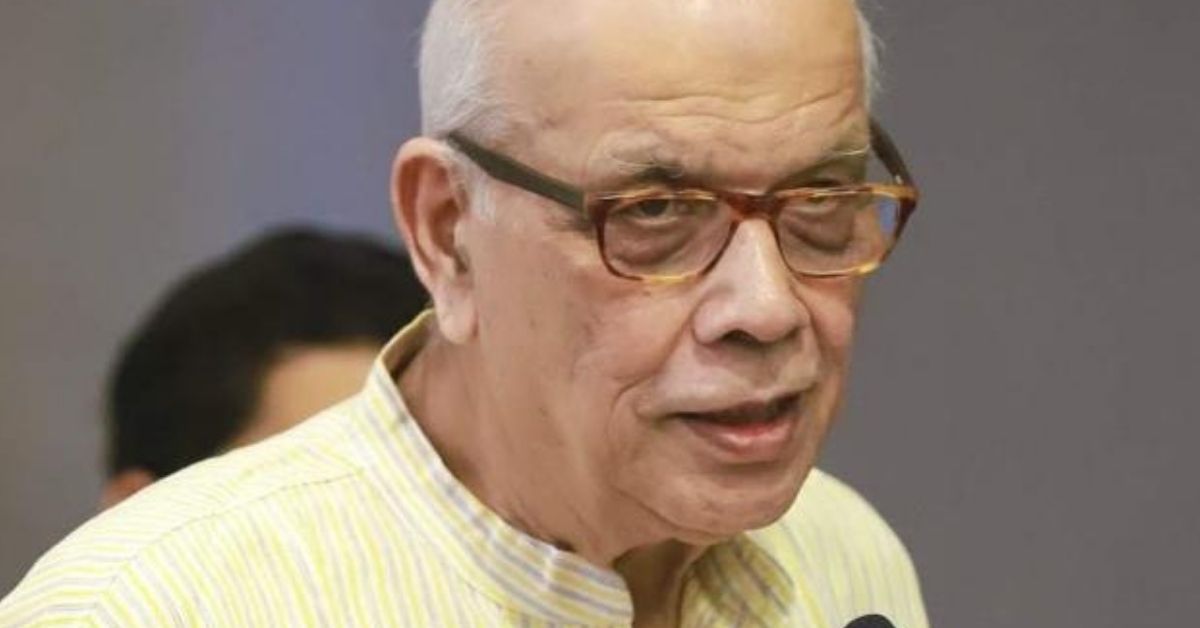

In India, the status, or even availability, of quality shelter or halfway homes remains dismal. Amrit Kumar Bakhshy (79), former president of the Schizophrenia Awareness Association, knows this all too well. “I’m old, tired, and have fought several battles. I helped my wife fight cancer for three years, and have been fighting my daughter Richa’s schizophrenia for 20 years. Since my wife’s death last year, I’m the only one who can care for Richa. This is the age where I need some help and support as well, but our conditions don’t allow for that. I don’t know how long I’ll be able to care for her — I don’t have much time,” he tells The Better India.

‘A constant shift between remission and relapse’

Richa is the Bakhshys’ only daughter. At the time of her diagnosis around 1991, her family was settled in Mumbai, and she was attending a boarding school in Dehradun. “Her symptoms appeared there first. My sister-in-law was her local guardian at that time. Her husband passed away, and Richa was the first one to witness his death. That might have been the trigger,” he says. Schizophrenia is present since birth, but might be triggered much later due to any tragic event.

Soon after, her parents called her back to Mumbai, and her father took her to a doctor there. “He gave us very wrong advice. He said this must be a one-time episode, and we didn’t have to worry. She was not provided with the medication she should have been given at the time,” he says.

She later got admission in Baroda University, which Bakhshy says was also a serious mistake, for it’s always better for such patients to stay near their families. “I met a psychiatrist in the city, who was to check on her from time to time. He kept the money and did not help at all. Her symptoms reappeared, and she fell into bad company. She got into smoking. Her friends would send her on their behalf to buy liquor. She would go around temples leaving Rs 100 notes. When we heard, we brought her back to Mumbai,” he says.

Richa refused to see a psychiatrist, and her parents would help her take medication by hiding it in her food. The effects began taking place. It’s been 30 years since, and Bakhshy says her recovery comes and goes in phases. There have been times when her recovery was so brilliant that everyone was sure it was permanent. “There are a very few lucky ones who permanently recover from mental illnesses,” he notes. “Otherwise, there’s a constant shift between remission and relapse, and it’s hard to pinpoint how the latter happened.”

Bakhshy says that when Richa was diagnosed, their entire lives changed. “Due to her erratic behaviour, relatives and friends stopped visiting. Neighbours became fearful that she was a threat to their children. Moreover, in India, invitations are addressed to Mr, Mrs, and family. We never get invites for the ‘family’. We can’t leave her alone and go out,” he says. Since it was not possible to leave Richa alone, Bakhshy’s wife took a year-long leave without pay, and had to eventually resign.

“My wife never believed in rituals. In fact, she never let Richa get her mundan done when she was a baby. But after Richa was diagnosed, my wife wondered if it was because we didn’t conduct the ceremony. We decided to get her head shaved, but Richa refused. To set an example, my wife shaved her own head. That’s the extent she went to. All the praying and rituals she never conducted in her entire life, she did when Richa became sick,” he says.

The creation of a safe space

In 2007, Bakhshy and his family relocated to Pune. “Pune and Bengaluru are generally better equipped as cities for the mentally ill. We moved to Pune thinking that Richa’s recovery might be easier,” he says. “I enrolled her in the Schizophrenia Awareness Association. We’d take her for visits during the day, and while she was in the rehab centre, I’d spend my time around the campus, reading or mingling with the persons there. I told them that I’d be happy to help if they needed any assistance. The founder was Canada-based Dr Jagannath Wani, whose wife also had schizophrenia. He would visit India twice a year, and we became good friends. Eventually, he offered me his position as president.”

Bakhshy was initially hesitant, given that there were many who had worked in the organisation before him. He offered to be a trustee instead, but Wani was determined. In 2010, Bakhshy became the president of SAA. He served for five years on the Institutional Board of NIMHANS, and was also chairperson of the Hospital Management Committee of the organisation for three years. SAA is one of India’s top centres for the rehabilitation of the mentally ill. The premises of the centre was expanded under Bakhshy’s tenure, and the institute started a centre for patients to socialise and mingle during the day, while their caregivers to carry out their jobs or other work.

“We don’t have a residential facility, because we believe that patients should not be kept isolated from the larger community. The idea is to bring in balance — if they remain home 24 hours a day, it won’t be good for them. But if they remain away from their families for too long, it won’t do them well either. Humans are social animals, and need to meet other people. Our counsellors take care of them in case of erratic behaviour, but this way, they’re not completely shut out from the world,” he says, and adds, “In the meantime, caregivers can do other jobs.”

Richa was this centre’s first patient, and now there are 40-50. The COVID-19 lockdown certainly was a hindrance, and the centre would then conduct online sessions for its patients. Bakhshy retired in 2019, but remains involved in the organisation’s day-to-day activities.

A small, yet steady step forward

In 2010, it was decided that changes need to be brought to the Mental Health Act of 1987. The Indian Law Society, Pune, was given the responsibility of drafting changes, and Bakhshy, who was president of SAA, was involved. When the committee noted the number of changes that needed to be made, it was decided that a new Act was needed. The Bill was introduced to the Parliament in 2013, and Bakhshy was also invited. He says the perspective of human rights drove the new Act. “For example, the new law puts restrictions on the use of direct ECT (electroconvulsive therapy). The treatment has been strictly prohibited on minors. The law dictates that general anesthesia and muscle relaxants need to be provided before the procedure,” he says.

The law also dictates that general hospitals with psychiatric wards need to go through a registration process so that a track of the number of beds in each can be kept. “We received criticisms for this, which said that many general and government hospitals would close down these wards to avoid going through the process. But the point here is that we need to maintain records for statistical purposes, and also that once these wards apply for registration, they have to maintain the standards mentioned in the Act, such as maintenance of hygiene, reduction of overcrowding, recreational spaces for patients, availability of an adequate number of toilets, sanitary pads for female patients, etc,” he says.

One aspect of the Act that was not included after protests by human rights’ activists was the independant admission of patients. “Say a patient is getting violent, and is a danger to themselves or others in the family and neighbourhood. Or they’re not in a position to care for themselves. In this case, they can be admitted forcibly as well. But the activists opposed this forcible admission, while we caregivers supported it,” he says. The caregivers say that in India, where families often hold more importance than personal autonomy, the new Act might inhibit doctors from making clinical decisions, thus shifting the burden on the former’s shoulders.

Bakhshy also says that despite the new law, the state needs to be far more active in its implementation of adequate facilities for the mentally ill.

The Swan song

“There were some aspects of the Act that weren’t included, but the changes from the previous Act are still monumental,” Bakhshy admits. “Before the 1987 Act, the mentally ill in India were governed by the Indian Lunacy Act, 1912. This was a British-era law. The Indian Psychiatric Society was formed in 1947, and it took 40 years before the next Act took shape. So we’re definitely moving forward. That’s why we supported it.”

The Bill remained in cold storage for a while, as the government changed in 2014. “Other political issues took precedence for some time. The government finally picked it up in 2016, and the Act was officially passed in 2017.”

Bakhshy has also authored one of India’s only books for caregivers in 2016 titled ‘Mental Illness and Caregiving’. “When my daughter fell ill in 1991, I hadn’t even heard of schizophrenia. The internet was very new, so I used it to go through Wikipedia and other such portals for preliminary information. Over the years, I have gained a lot of knowledge and experience. I wanted to pass on this critical knowledge to other families with similar stories,” he says.

To increase the reach of the book, Bakhshy is working to have it translated into Hindi (a Marathi translation already exists), as well as a new edition with updates since the Act was passed. The book is set to be published by May 24, which is Schizophrenia Awareness Day. “I want it to be a Bible for caregivers in India. This will be what they call a swan song — my parting gift to the community,” he says.

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

No comments:

Post a Comment