Three women stand tall, dressed in regal sarees and adorned with bedazzling jewellery in a portrait of the early 19th century. They offer half-smiles and pose casually while exuberating the sense of royalty you’d associate with any queen. Almost unwittingly, these young women have become part of what is arguably one of the first mass awareness campaigns not just in India, but worldwide, for the cause of vaccination for smallpox.

Vaccination Day, 16 March, is marked to emphasise the importance of immunising the entire country. This day, also known as National Immunisation Day, was first observed in 1995 when the country began its Pulse Polio Programme. This year, the day holds tremendous significance, as the country has embarked on a massive immunisation programme in the face of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Three queens from Mysore were chosen to spread the positive message of vaccination by the then British government. Their story dates back to sometime around 1805.

The one on the right has been identified as Queen Devajammani, according to Dr Nigel Chancellor, historian at Cambridge University. She arrived at the royal court that year, to be wed to Krishnaraj Wadiyar III, when they were both 12 years old. But her commemoration in history came in the form of an oil painting done by Thomas Hickey, an Irish painter who was noted for his paintings of the royals of Mysore. The portrait was last offered for sale in 2007 by Sotheby’s Auction House.

The need for the portrait came about due to general public resistance towards vaccination. The vaccine for smallpox had arrived in India by 1802, but its spread was slow in the first half of the 19th century. The cure had been discovered just six years before by British doctor Edward Jenner but was met with resistance and suspicions by Indians, possibly because it was being championed by oppressors, who were steadily gaining a stronger hold over the country at the time.

The discovery of the portrait

The high cost of inoculating Indians was justified with the “numerous lives” that would be saved, and a promise of “increased resources” that could be derived from an abundant population if people chose to be vaccinated. As per the BBC, the East India Company involved several British surgeons, Indian vaccinators, businessmen and royals to initiate the drive. The Wadiyars were among them, for they were indebted to the British, who had restored them to the throne of Mysore after over 30 years of exile.

In 1991, Dr Chancellor came across the painting in an exhibition. Its subjects were unknown, and were thought to be dancers or courtesans, which Dr Chancellor “immediately felt was wrong”. He identified the woman on the right as Devajammani. Her saree would ideally have covered her left arm, but was left “exposed” to signify the place at which she had been vaccinated without “compromising on dignity”. Dr Chancellor said the woman on the left was also named Devajammani and was the king’s first wife. He also believed the woman in the middle was Lakshmi Ammani, the king’s grandmother, who wished to encourage queens to be vaccinated after losing her own husband to smallpox.

Meanwhile, on carefully looking upon the portrait, one finds that the king’s first wife has been marked with discolouration under her nose and around her mouth. This, Dr Chancellor said, was consistent with the measures that were being taken to control smallpox at the time. Pustules and spots from recovered patients would be extracted, ground to dust, and blown on the noses of those who had not been infected yet. This was known as variolation.

Countering mass resistance

To understand why the queens were chosen as the faces of the vaccination drive, we must understand the urgency with which the Brits wanted to vaccinate the Indian populace. As per The Indian Express, British and Indian officials were engaged in a long and arduous battle against general public unwillingness to be inoculated. This was for a number of reasons.

For one, the variolator (or tikadar) was part of India’s already-existing method of developing immunity against the disease. Tikadars would first purify the scabs in the River Ganga, and the subjects would have to prepare for the inoculation by abstaining from fish, milk, or ghee. To negate the influence of these tikadars, pensions were granted in 1805 to those who were willing to give up their practices.

Around 50 years later, variolation would be considered akin to sati and infanticide. Tikadars were thus threatened by the new vaccine.

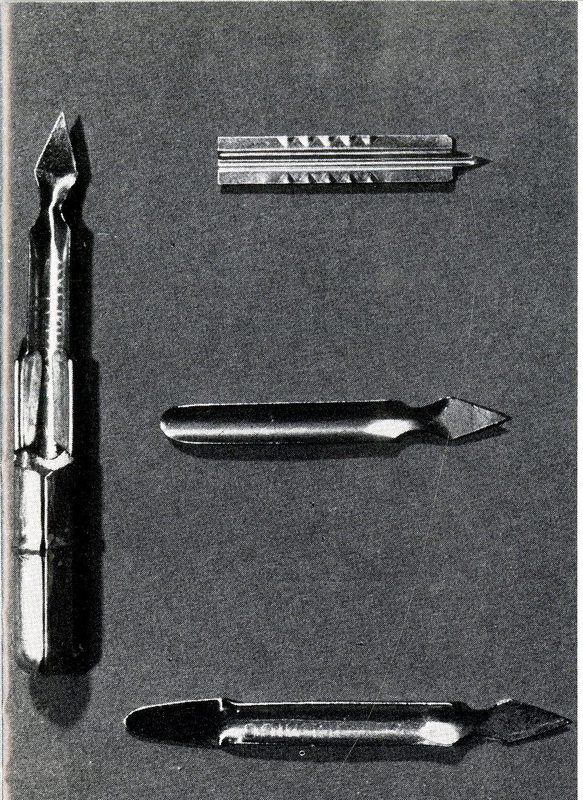

Moreover, vaccinators were viewed as terrifying, looming figures who were often associated with pain and terrifying sharp instruments. After all, the process back then was not the quick, almost painless jab we feel today. Instead, it used painful lancets through what was known as the “arm-to-arm” method. Here, a person was vaccinated by smearing the vaccine onto their arm with a needle or lancet, and a week later, a pustule would develop in the spot, which doctors would cut and transfer the pus onto the arm of another person. The lymph from the arm of a patient would be dried and sealed to be transported elsewhere but would often not survive the journey due to the country’s hot climate.

A symbol of ‘purity’

Another aspect of resistance from the masses was that the vaccine consisted of the cowpox virus, which caused major concerns around “polluting” healthy children with cattle disease. Besides, this vaccine did not see the clearly defined lines of race, religion, castes and genders. This was a stark contrast to the Hindu notions of purity at the time. Enlisting Hindu royals, whose power was “tied to their bloodlines”, seemed like an effective way to overcome these fears.

To support his theory regarding the identity of these women, Dr Chancellor obtained court records from 1806, which stated that Devajammani’s vaccination had “a salutary influence” on civilians, who came forward to be vaccinated thereafter. As an expert in the history of Mysore, he was also sure that the “heavy gold sleeve bangles” and “magnificent headdresses” were characteristics of Wadiyar queens. The third reason was the association of Thomas Hickey, noted for painting the royals of Mysore.

Years of records and documentation denote that several other royals were vaccinated, but none find a permanent place in history the way these three queens of Mysore do. The betrothal of a young girl would present itself as the perfect opportunity for the then British government to ensure mass immunisation, and in turn protect its own expats. So not only are the queens a part of India’s history, but also significant in their preliminary role in immunisation campaigns worldwide.

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

No comments:

Post a Comment