Flora: “While having tiffin on the veranda of my bungalow, I spilled kedgeree on my dungarees and had to go to the gymkhana in my pyjamas, looking like a coolie.”

Nirad: “I was buying chutney in the bazaar when a thug who had escaped from the chokey ran amok and killed a box-wallah for his loot, creating a hullabaloo and landing himself in the mulligatawny.”

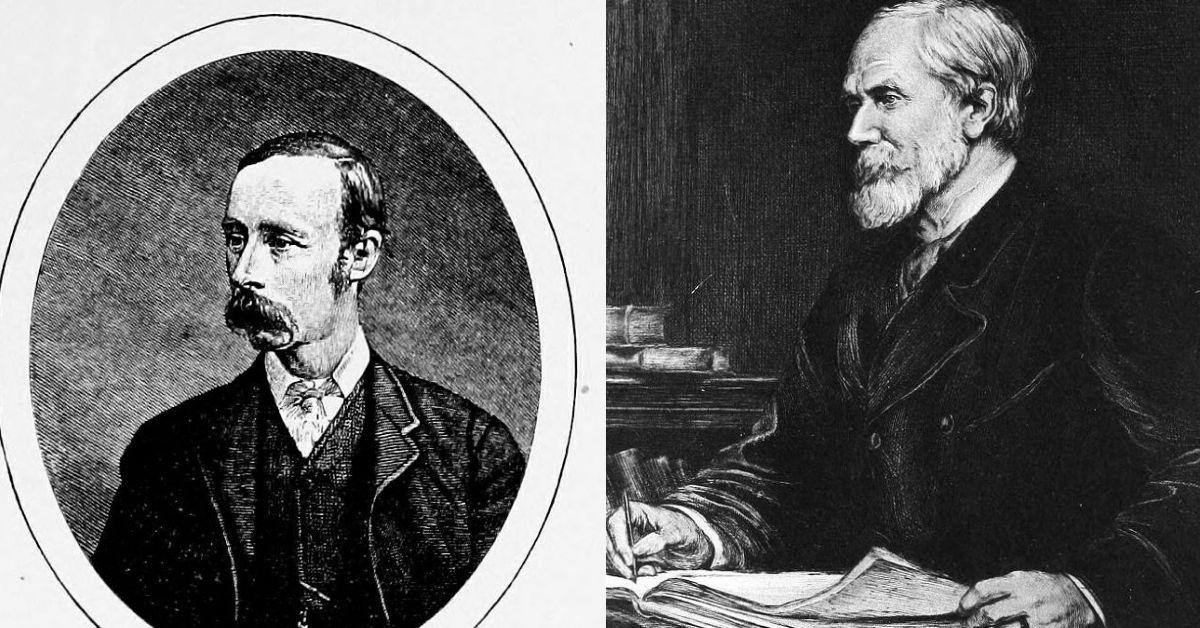

This is a conversation between two characters from Tom Stoppard’s play, India Ink (1995), who are engaged in a battle to see who can construct a sentence using as many words as possible from the Hobson-Jobson — a compendium of Anglo-Indian words and phrases used during the British Raj. The dictionary has an absurd name, perhaps based on what was then an absurd yet intriguing language for its authors, Englishmen Sir Henry Yule and Arthur Coke Burnell.

The full name of the dictionary is Hobson-Jobson — A Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words and Phrases, and of Kindred Terms, Etymological, Historical, Geographical and Discursive. The use of the word ‘discursive’ here is apt, for the text does not read like a straightforward dictionary, but rather a memoir of colonial India.

Entries include details of places, people, occupations, celebrations, food, religions, and castes. And some entries run pages long.

But how did this glossary, which contains words of Indian origin that were later absorbed into the English language, come about?

A common love for language

Burnell and Yule were acquainted in 1872, when the two met at the India Office Library. Both men were ardent enthusiasts of language. Yule arrived in Calcutta in 1840, and his first posting was in the Khasi Hills to establish a viable method of transporting coal to the plains. He was unable to find such a method, but what he did find was an intense fascination with the region and the people. He wrote an account of his experiences with the locals, and this included what was the first written account of living root bridges.

Burnell, meanwhile, took up a posting in Madras Presidency in 1860, after writing his Indian Civil Service exams in 1857. He has been credited with having done extensive work on Sanskrit, and making immense contributions to western scholarship. While writing his Indian Civil Service exam, he noted Arabic as his oriental language, but would later go on to master Sanskrit, Portugese, Dutch, Italian, Javanese, Coptic, and Tibetan.

After their meeting in the library, it was Yule who suggested that the two combine their linguistic prowess to formulate a glossary. What followed was 14 years of complaining of the copious amounts of knowledge the two Englishmen had gained from India, and the encyclopedic Hobson-Jobson was finally printed in 1886. The odd name comes from the Arabic chant of ‘Ya Hasan! Ya Hosain!’ — the chant used during the Mourning of Muharram. It’s an anglicised interpretation of foreigners who could not understand the exact nature of what was being said. The name also denotes the penchant of Indians for double words such as naukar-chakar, alongside the dual authorship of the text.

Yule and Burnell shared a strong camaraderie, as is evident in Yule’s acknowledgement of Burnell’s prowess in the introductory note of the dictionary. “…Burnell contributed so much of value, so much of the essential; buying in the search for illustration, numerous rare and costly books which were not otherwise accessible to him in India; setting me, by his example, on lines of research with which I should have else possibly remained unacquainted; writing letters with such fullness, frequency, and interest on the details of the work up to the summer of his death; that the measure of bulk in contribution is no gauge of his share in the result,” he wrote.

Burnell, who had suffered from ill-health most of his life, died due to cholera and partial paralysis four years before the book could see the light of day.

As Kate Teltscher, who published a new edition of the book in 2013, said, “[The book] shows how words of Indian origin were absorbed into the English language and records not only the vocabulary but also the culture of the Raj. Illustrative quotations from a wide range of travel texts, histories, memoirs, and novels create a canon of English writing about India. The definitions frequently slip into anecdote, reminiscence, and digression, and they offer intriguing insights into Victorian attitudes to India and its people and customs.”

‘I won’t give a ‘dumree’!’

In its introductory remarks, the book talks about how “words of Indian origin have been insinuating themselves into English ever since the end of the reign of Elizabeth and the beginning of that of King James, when such terms as calico, chintz, and gingham had already effected a lodgment in English warehouses and shops, and were lying in wait for entrance into English literature.”

Over 2,000 words in the English language originate from India, many of which—shampoo, thug, pyjama, chilly—continue to be used. They made their way to the world through this extensive piece of work. The book finds relevance even today, two centuries later. Take, for example, the word damri, which gave rise to one of the most commonly used phrases ‘I don’t give a damn’. A damri was a copper coin that once existed but now finds relevance only in Urdu idioms to signify something worthless.

The dictionary defines it as “originally an actual copper coin. Damri is a common enough expression for the infinitesimal in coin, and one has often heard a Briton in India say, ‘No, I won’t give a dumree’, with but a vague notion of what a damri meant”.

The description for the word ‘mango’ goes on for pages. The authors write, “The royal fruit of the mangifera indica, when of good quality is one of the richest and best fruits in the world. The origin of the word is Tamil man-kay, i.e. man fruit, (the tree being mamarum ‘man tree’). The Portuguese formed from this manga, which we have adopted as ‘mango’.” Similarly, we learn that chilly is the “popular Anglo-Indian name of the pod of red pepper…There can be little doubt that the name…was taken from Chili in South America, whence the plant was carried to the Indian Archipelago, and thence to India.” And who doesn’t know what chilli means now?

Mulligatawny, a popular soup originating in Southern India, finds mention as well. “The name of this well-known soup is simply a corruption of the Tamil milagu-tannir ‘pepper water’; showing the correctness of the popular belief, which ascribes the origin of this excellent article to Madras…” notes the dictionary. Providing insight into attire, we see the entry cummerbund, which today is worn as part of a man’s formal attire. Originally kamar-band, it originated in Persia, and was adopted by British military officers in colonial India when they saw it being worn by Indian soldiers of the British Indian Army.

Some more words that have Indian origins include coir, the outer husk of the coconut, which comes from Malayalam word kayaru, bandana, which is a piece of cloth worn around the neck or on the head, comes from the Hindi word baandhana (to tie something up), or catamaran, a boat built using logs of wood, comes from the Tamil word kattu (binding) and maram (wood).

Hobson-Jobson also explains India’s constructs of caste, which “according to Indian social views [dictates] high or low”, and goes on to explain how “in Madras Presidency [the words also mean] ‘Right-hand’ and ‘Left-hand’. This distinction represents the agricultural classes on one side, and artisans on the other…The word is current in French. Caste is also applied to breeds of animals, as ‘a high-caste Arab.’ In such cases, the usage may possibly have come directly from the Portuguese alta casta, casta baixa, in the sense of breed or strain.”

The dictionary also provides contexts of geographical areas such as Madras, detailing how one fictitious legend derives the name from “an imaginary Christian fisherman named Madarasan”, as well as areas such as Punjaub, Gurjaut, Cochin, Dacca, and Chowringhee. Each word in the dictionary comes with its earliest usage, examples in sentences, legend and anecdotes associated with the name, and other such interesting details that the authors painstakingly combined over the years.

Currencies of the time find a mention as well, in Pardao, a “popular name among the Portuguese of a gold coin from the native mints of Western India, which entered largely into the early currency of Goa”, cowry, (kauri in Hindi), a shell currency used as money at the time extensively in parts of South Asian and Africa, and the rupee, or rupiya, the “standard coin of the Anglo-Indian monetary system”. The dictionary records services of the time, such as sahib, “the title by which, all over India, European gentlemen…are addressed, when no disrespect is intended by ‘natives’,”, the consumah or khansama, the “chief table-servant and provider” in “Anglo-Indian households in the Bengal Presidency”, and duftery or daftari (Hindi), “a servant in an Indian office (Bengal), whose business is to look after the condition of the records, dusting and binding them; also to pen-mending, paper-ruling, making of envelopes…”

Around 1,000 pages and 14 years of work have encapsulated India from two perspectives — the coloniser and the colonised. It would be remiss to not understand how the utter European nature of the authors influences this piece of literature, and how the book, in its essence, is still a compilation of a country amid a long struggle for independence.

When we discuss the things that the British gave to India, the conversation is only complete with the acknowledgement of what India has given the British, and even the world, in return.

Edited by Yoshita Rao

No comments:

Post a Comment