The year is 1925, and the Assam Sahitya Sabha is holding a session in Nagaon district, Assam, to discuss the importance of educating women. Present at the conference are both men and women, but they’re separated by a barrier constructed from bamboo, with the women sitting behind it. It’s ironic, because here’s a gathering to discuss how women deserve equal opportunities as men, and yet, the distinction between the two could not be clearer. One woman present at the conference is quick to note this. She stands up at the mic, and tells the women to remove the barrier and sit with the men. And as the women break down the barrier in the meeting, a larger, metaphorical barrier between men and women is shattered as well.

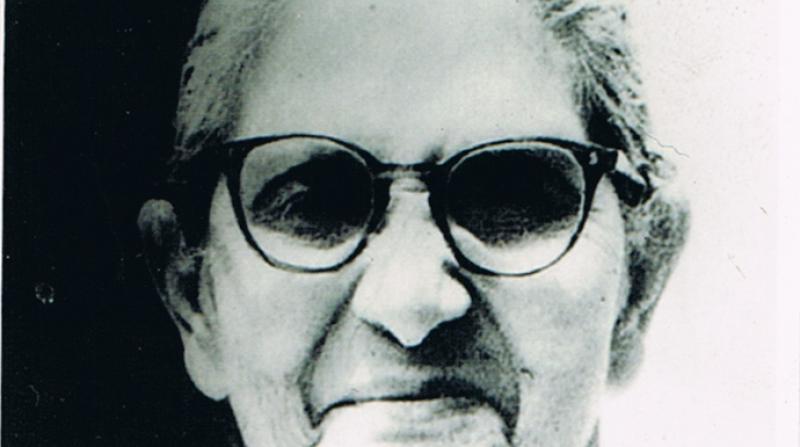

This woman was 24-year-old Chandraprabha Saikiani. As a social activist, she spent her entire life fighting to give women the rights they deserved, but alongside, led a tumultuous life that shaped her larger fight.

Breaking down barriers

Chandraprabha was born in 1901 in Daisingari in Assam’s Kamrup district. Her father, Ritaram Mazumdar, was the village head, and she was the seventh of 11 children that he and his wife, Gangapriya had. Ritaram was a firm believer in education, and urged his daughters to work and study hard. Along with her sister Rajaniprabha, she would wade through waist-deep mud water every day to reach the closest boys’ school, as there was no girls’ school nearby.

She was all but 13 when she brought several young girls under her wing to establish a girls’ school in Akaya village. The girls studied in a shed and Chandraprabha would impart whatever knowledge she had gained from attending school herself. Here, a man named Neelkanta Barua, a school sub-inspector, spotted Chandraprabha. Moved by her dedication, awarded her and Rajaniprabha a scholarship to study in the Nagaon Mission School. Rajaniprabha would later become the first woman doctor in Assam.

At the Mission school, Chandraprabha found that there was a clear distinction between Hindu and Christian students. Girls were not allowed to stay in the hostels unless they converted to Christianity, and thus began her relentless efforts to allow the induction of Hindu students in the hostel. Her efforts proved to be successful, and authorities allowed girls in the hostel without forcing them to convert to Christianity.

At 17, she took charge to address a large crowd to call for a ban on opium. At the time, a woman speaking at a public gathering, much less expressing a strong opinion, was not just frowned upon, but even unheard of. The prevalent evils of the caste system deeply perturbed her, and she worked to successfully open the doors of the ancient Hajo Hayagriva Madhav Temple for everyone, irrespective of caste, gender or religion.

In 1921, Chandraprabha joined the non-cooperation movement and worked to mobilise women in Assam to do the same. This eventually paved way for the establishment of the Assam Pradeshik Mahila Samity, which she launched in 1926. The organisation, which is still running almost a hundred years later, took charge of dealing with issues related to women’s education, prevention of child marriage, employment for women, and emphasis on handloom and handicrafts. This was also Assam’s first organised women movement, and even today, follows the ideals laid down by Chandraprabha. She was also the editor of Abhijatri, the magazine of the Mahila Samiti, for around seven years. She was also a noted and prolific writer, who went on to publish several books, including Pitribhitha (The Paternal Home) (1937), Sipahi Bidrohat (Sepoy Mutiny), and Dillir Sinhasan (Throne of Delhi).

Without conforming to norms

As progressive as Chandraprabha was, her marriage was customarily fixed by her parents with a man who was much older than her. However, she refused.

In those days, she was in Tezpur, having been appointed as the headmistress for the Tezpur Girls’ ME School, and met poet and author Dandinath Kalita, whom she fell in love with. She chose to be with him, and despite her getting pregnant with his baby, Dandinath was not the rebel that Chandraprabha was. He wished to align more closely with societal norms and what was expected of him at the time. As she belonged to a non-dominant caste, Dandinath went ahead and married a girl of his parents’ choosing, who was younger and from the same caste as him.

In the mid-20th century, Chandraprabha was now alone to fend for herself amidst a society that strongly looked down upon unwed mothers and their children born without a father figure. If this was daunting, she never let it show, and raised her son single handedly for the remainder of her life. She instilled in him the ideals that she had always believed in, and her son went on to become a notable figure in the Trade Union Movement of Assam. He was a Congress legislator, but was known to often land the government in hot water by raising questions regarding the unfair exploitation of the working class.

In Tezpur she would go on to interact and work with imminent social workers such as Omeo Kumar Das, Jyotiprasad Agarwalla and Lakhidar Sharma. Her involvement in the Civil Disobedience and Non-Cooperation movements landed her in jail twice, and after India attained independence, she became the first Assamese woman to contest in an election in 1957, albeit unsuccessfully.

She eventually passed away on her 71st birthday on 13 March 1972, after a battle with cancer, and the Government of India awarded her the Padma Shri shortly after her death. In 2002, she was also commemorated on a postage stamp, and the Girls’ Polytechnic Institute in Guwahati was renamed in her honour. But these recognitions, which perhaps arrived a little too late, pale in comparison to the groundbreaking work she spent her entire life doing.

To say that she was ahead of her time would be an understatement, and her critical thinking beyond the confines of what was acceptable has undoubtedly shaped the modern feminist movement and the strive for equality.

Edited by Yoshita Rao

No comments:

Post a Comment