Characterised by the layered interlocking of wood-and-stone, the stone plinth, double-skinned walls, and intricate wooden carvings, Kath Kuni architectural structures, native to Himachal Pradesh, are the epitome of beauty. However, there’s more than what meets the eye. The structures have stood the test of time, and have survived for centuries in regions that frequently experience seismic tremors and earthquakes.

Kath Kuni is derived from two words, kath, meaning wood in Sanskrit, and kona, which means corner. True to its name, the indigenous architectural style is highly influenced by the region’s topography, and predominantly uses local resources such as wood and stone of the Himalayan landscape.

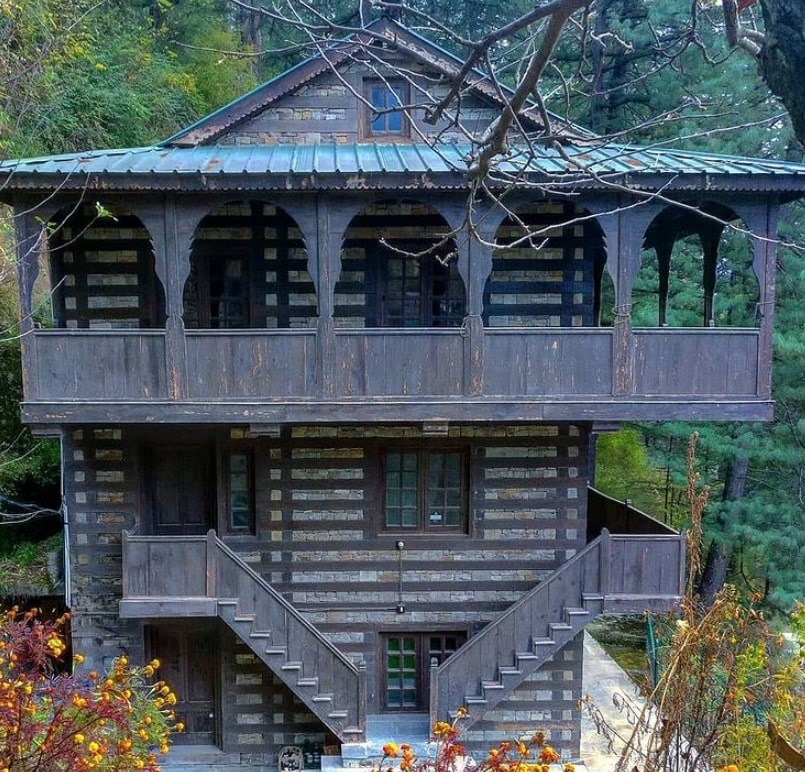

In Himachal, you would spot this kind of vernacular style in Kullu district, especially in the villages of Naggar, Old Manali, Chehni Kothi and Malana. From majestic temples such as Hidimba and Naggar Castle (built around 1460 AD) to modest houses, Kath Kuni can be implemented in all types of structures.

Although the structures are timeless and have escaped natural calamities unscathed, Kath Kuni is a dying craft. The reason for this is the heavy influx of brick and concrete-based material construction palettes.

Perturbed by the dwindling glory, Rahul Bhushan, a Himachali local and alumnus of CEPT and IIM Ahmedabad, took it upon himself to not only restore old structures, but also build new ones in the region. In 2017, he started his firm, NORTH, to promote local craftsmanship and conserve the ancient practice.

While he’d always been aware of the plight of the buildings, which were disappearing as he was growing up, Rahul’s final motivation to do something about it came during his final year at CEPT. He did his thesis on how the indigenous building practice was being replaced by modern ones.

View this post on Instagram

Rahul worked as a professor at CEPT for a brief period, before kickstarting a government restoration project of an old forest house in 2017. He worked on the Kath Kuni-style house for three months, and converted it into a guest house. That project left him wanting to do more, and he moved back to his native place for good.

The 29-year-old speaks to The Better India and shares the process and material used in Kath Kuni architecture, and how responsible architectural practices can preserve the pristine glory of the Himalayas in a world of rapid concretisation.

A clever design

Rahul has an emotional and nostalgic connection with the Naggar valley. He has spent most of his summer vacations at his grandparents’ house in the mountains. The old charm windows and balconies that allowed direct sunlight inside, the compact groundfloor that absorbed heat — Rahul found himself interested in decoding the design of the Kath Kuni buildings.

“The foundation material includes stone and wood, which have been used since 600 AD. Just like local dialect, architecture differs from region to region, and due to easy access, these two materials dominate the construction in all houses,” says Rahul.

The Cedrus Deodara (Deodar/Devidar) wood is used for its highly durability, and lasts up to a thousand years, like it has in the Naggar Castle, built by Raja Sidh Singh about five centuries ago. It stands unharmed even since a massive earthquake in 1905.

Explaining the benefits of stone and wood, Rahul says, “The deodar wood lasts longer, has more fibre and can be reused. However, to use deodar, we have to take permission from the state forest department to ensure it is not rampantly exploited. Meanwhile, the stone is heavy-weight and holds enough gravity to make the house durable.”

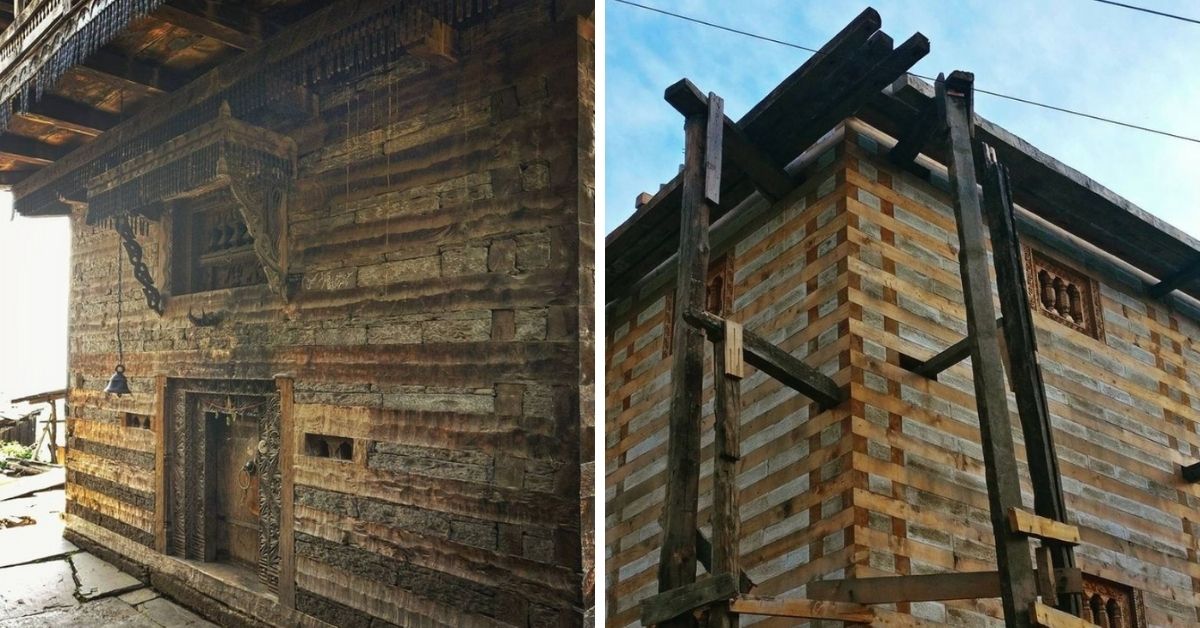

Explaining the process, Rahul says that after digging the trench, the raised bed is made of stone blocks. This provides stability and prevents water or snow from entering the house. Next, double-skin exterior walls are made with alternate layers of dry stone masonry and wood. Instead of metal nails, the architects use a wooden brace to hold the resilient structure. This makes the house sway in the direction of the seismic waves, without being uprooted.

“A typical house will have 2-3 floors. Upper levels have less stone and more wood. The interiors are plastered with mud for insulation purposes, and cement or RCC is strictly avoided. The structure is broader on the upper level, which integrates a cantilevered balcony on all sides of the house. Open balconies allow dwellers to soak heat during the day. The lower floors are narrower, and without windows. The house only absorbs heat, and radiates it in the evening. The air gaps between stone and wood diffuse the seismic force and prevent any cracks. Thus, the structure, cleverly designed by our ancestors, gives utmost importance to thermal insulation,” adds Rahul.

Highly intricate wood carvings are another indispensable feature of Kath Kuni. The art mirrors local aesthetics, folk traditions and ancient customs of Himachal. These carvings are usually done on doors, handles, windows, balconies and walls. Only highly skilled and veteran artisans can get it right, says Rahul. These carvings include motifs and wooden pendants infused with geometric or folklore themes. The intensity of the work is usually high in temple structures.

‘Art and sustainability go hand-in-hand’

In the last three years, Rahul has undertaken nearly 20 projects (restoration and new constructions). These are versatile projects including the massive restoration of Naggar castle. His next project is a Kath Kuni-style restaurant in Kullu.

“I have worked on private and government properties, including houses, restaurants, commercial spaces and so on. Since the cost of a Kath Kuni structure is higher than other vernacular houses, my organisation focusses more on preserving existing structures through restoration work,” he says.

The restoration process typically involves solving technical challenges, such as replacing decaying wood and other eco-friendly materials without compromising on the essence of the structure. To make the construction process affordable, Rahul even experiments with mixing other traditional styles like the Dhajji Dewari or Lahaul, thereby reducing wood usage. He also reuses wood from dilapidated structures to save additional expenses.

“It takes extensive research and planning to build a structure incorporating all-natural elements, while ensuring that we are not overusing wood, which happens to be a depleting resource. This is one of the reasons why modern structures have replaced Kath Kuni houses. I want to reiterate again that conserving our existing structures is a great way to preserve this architectural style,” says Rahul.

In his recent project, an Ayurvedic centre, Rahul reused wood. Vijendra, the owner, says by that reusing the wood, his centre not only incorporated eco-friendly aspects, but also preserved his ancestor’s legacy, “Our Kath Kuni-style house was dismantled a few years ago. The wood and other material from the house were incorporated in the centre. I am glad I was able to keep alive our local tradition, while being sustainable in our approach,” he tells The Better India.

Besides these projects, Rahul is also actively engaging with local communities, artisans and fellow architects to spread awareness on Kath Kuni and other eco-friendly traditional practices. His studio takes workshops on skill development for artisans on wood carvings, handloom, etc. He also collaborates with the government to organise lectures on the importance of architecture in eco-tourism and conservation processes.

“The idea is to build a platform that initiates and continues dialogues on local heritage, material and communities. Art and sustainability go hand-in-hand, and this idea must be promoted on a large scale. Most researchers visit the Himalayas to study, but the solutions are limited to the ideation stage. My organisation is trying to change that by executing projects,” he adds.

It is very rare to see passionate people like Rahul going back to the basics and working strenuously to preserve their culture. No amount of lucrative opportunities could prevent him from doing what is right for his community and the environment.

You can reach Rahul here

Edited by Divya Sethu

No comments:

Post a Comment