Several questions surround the identity of mythical King Chandraketu. Was he a valiant king who refused to accept Islam and in turn lost his kingdom? Or was he Sandrocottus, who was documented by ancient Greek explorer Megasthenes in his book Indika? Recent discoveries have leaned towards the latter, with new theories suggesting that while it has always been believed that Sandrocottus was the name Megasthenes used for Chandragupta Maurya, he was talking about his time spent in India with King Chandraketu. However, his historical presence remains ambiguous with several authorities believing he was entirely fictitious. No written records of such a king exists in Bengali medieval literature.

Chandraketugarh (Fort of Chandraketu) remains a lesser known chapter in history. Often called “the city that never existed”, it was once reportedly an important coastal hub in international trade, between 4th Century BCE and 12th Century CE. However, it has since been reduced to a barren mound, with the ruins having spent years being neglected. The archaeological site is over 2,500 years old, and is located near the Bidyadhari River, which is around 35 kilometres north east of Kolkata, in North 24 Parganas, near Berachampa and the Harua Road railhead.

A civilisation shrouded in mystery

Its discovery was chanced upon during construction which was undertaken on adjacent roads. In 1907, local resident Dr Tarak Nath Ghosh approached the local government with a request to look into this site. He also wrote to Albert Henry Longhurst, a British archaeologist and historian, and an official of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). However, Longhurst deemed the site “of no interest”, and the ruins lay forgotten for two years.

In 1909, historian Rakhaldas Banerji—years before he discovered the ruins of Harappa and Mohenjodaro—arrived at the site. He shared similar opinions as Longhurst that the structural remains were little to work upon. But what intrigued him were the artefacts that had been found thus far and presented to him. He published a preliminary report on his findings in Basumati, a Bengali monthly. Almost a decade later, K N Dikshit, then superintendent of the eastern circle of ASI, published a report on the ruins.

In 1955, through efforts taken by several historians and archaeologists, the Ashutosh Museum of Art, Calcutta University, decided to excavate the site. The excavation was carried out between 1955 and 1967 at Khana Mihirer Dhibi, a five-metre high mound at the northeast corner of Berachampa village. This led to the discovery of a giant post-Gupta temple complex, the findings of which proved the existence of a flourishing ancient civilisation which possibly spanned six periods from the pre-Maurya to the Pala dynasty. Then, in 2000, another excavation was undertaken but remained incomplete and its reports were unpublished.

The findings over the years include the aforementioned Khana Mihirer Dhibi, a sub-site which is said to be a structure belonging to the Gupta period, and is named after two notable figures in history. Khana is believed to be the daughter-in-law of astrologer and mathematician Varahamihira, and a notable medieval Bengali language poet and astrologer herself, somewhere between the 9th and 12th centuries CE. The mound discovered in Chandraketugarh had the names of Khana and Mihir (another name by which Varahamihira was known). Varahamihira was believed to be part of emperor Vikramaditya or Chandragupta II’s famed navaratna sabha. Legend goes that because Khana was such an accomplished astrologer that Varahamihira’s career was threatened because she surpassed his accuracy in predictions. The story ends with either Khana’s husband or father-in-law cutting off her tongue to silence her talent.

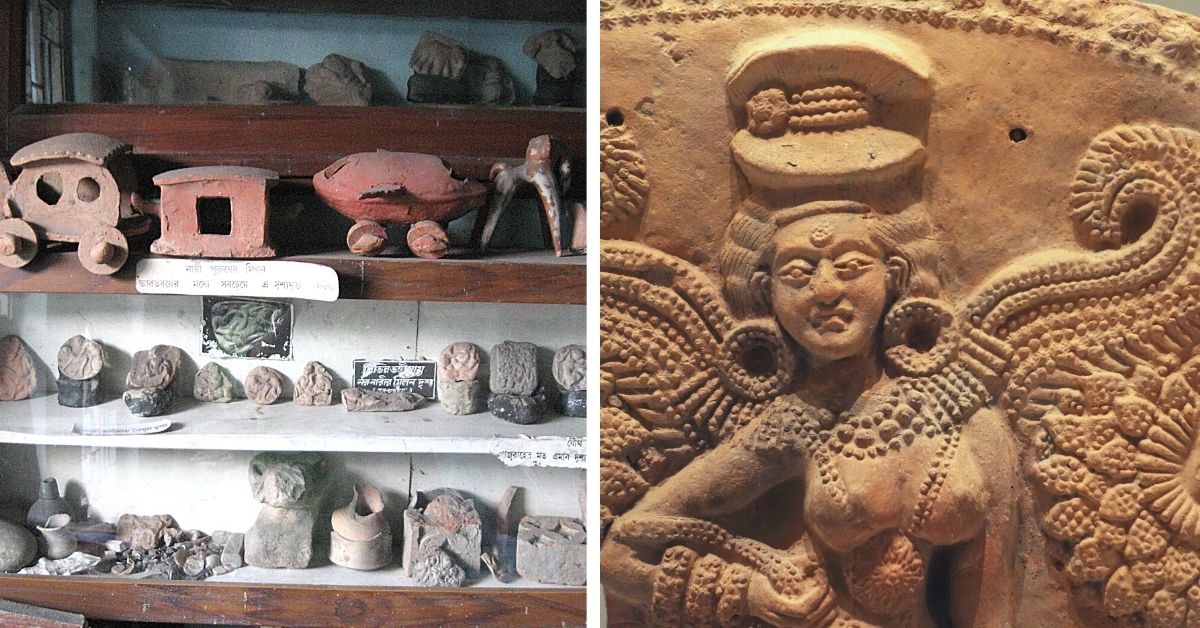

Other discoveries helped understand several phases, ranging from the Mauryan to the post-Gupta period. Findings included large-sized pots and chalcedony beads possibly dating back to Mauryan times. Semi-precious stones, copper coins, terracotta figurines, cosmetic sticks of bone and ivory, and a steatite casket. Chandraketugarh is the only early historic site that has yielded such a massive amount of terracotta through excavation, so far recorded in eastern India.

A wide variety of figurines, animals, toy-carts, erotic depictions, narrative plaques depicting sceneries of harvest, aquatic motifs, among others, have been unearthed. Some of these terracotta items date back to the Indus Valley Civilisation, and are a window into the ways of life of the people. The female figurines are adorned with intricate headdresses, earrings, pendants, and other accessories that show the stellar craftsmanship of the civilisation.

A victim of neglect

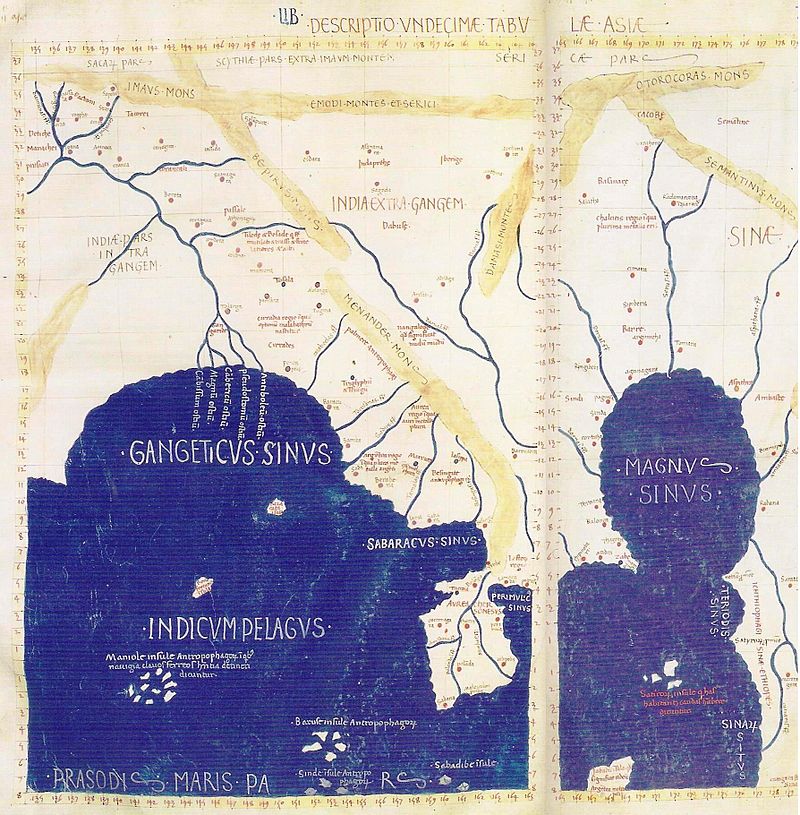

Some historians also identified Chandraketugarh as Gangaridai, one of the four places that Greek philosopher Ptolemy mentions in his work — Geographia. This may suggest that the site had links with Rome and other ancient civilisations, and was part of a wide network of metal trading. The coins unearthed in excavations are telling of this.

After the 2000 excavation, evidence of a 30-foot rectangular fort, dating back to somewhere between the Maurya and Gupta periods, was found. The team also found structural remains of a temple. When the site was abandoned in 2001, it was left vulnerable to several thefts. People have managed to include items unearthed in their collections, and over the years, several artefacts have made their way to international museums such as Musee Guimet in Paris, as well as Sotheby’s. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in the US displays unprovenanced antiquities from Chandraketugarh, as gifts received from arrested art dealer Subash Kapoor.

In 2016, All-India Trinamool Congress MP, Kakoli Ghosh Dastidar, raised the issue of Chandraketugarh’s neglect in Parliament and wrote to the Centre as well. “In a place called Chandraketugarh in Berachampa, which is within my constituency of Deganga…Maritime was carried out with Europe 2,000 years ago. Seals, terracotta figurines recovered are getting lost…Mamata Banerjee had formed the Heritage Commission and excavation had started under the Archaeological Survey of India. We were expecting it to become a United Nations heritage site, but the excavation stopped. I draw your notice…and through you, the Hon’ble Minister of Culture, so that this place of heritage should find its place of prominence within our country,” the MP said.

Finally, in 2017, it was announced that a museum would be made to store the findings of Chandraketugarh. Art collector Dilip Maite donated 524 artefacts from his collection to the government for this museum, and their estimated value is around Rs 300 crore ($41 million).

Chandraketugarh finds itself mentioned more in newspapers and the media for these thefts and illegal activities than it ever has in the pages of history. A report by Sahapedia cites several reasons for its neglect. One is the larger problem of archaeological research in India, particularly that of coastal sites. Elements of coastal life are largely different from land-bound areas, right down to the geography. Moreover, owing to the volatile nature of these coasts, where places are often submerged and destroyed, these sites are even more difficult to excavate.

Another reason is the lack of textual or epigraphic material. Sources that mention Gangaridai do not point to a specific location where Chandraketugarh could have been located. No inscriptions with specific names of a place, king, or kingdom have been found either. And the legends surrounding the true identity of King Chandraketu only add to the mystery.

A detailed list of the artefacts uncovered in Chandraketugarh can be found here.

No comments:

Post a Comment