About 10 and a half minutes into freelance filmmaker Hemant Gaba’s National Award-winning documentary, An Engineered Dream, an IIT coaching academy teacher is seen telling a group of 15 to 16-year-old students: “This period of nine months is similar to the nine months you were in your mother’s womb… Forget everything else, just remember your parents’ faces the day you left them to come here. You are doing this for them.” As the documentary progresses following the lives of four teenagers from different corners of India to Kota—a city famous for its coaching centres—in Rajasthan, it’s hard not to escape the kind of indoctrination or ‘brainwashing’ that students sent there undergo.

For the duration of their high school, these students cage themselves in cubicle-sized rooms to prepare for the Joint Entrance Examination (JEE) to the Indian Institutes of Technology (IIT). Every year, 150,000 students make their way from small cities, towns and villages to Kota to get admission into the IITs. With an acceptance rate of less than 1%, it’s one of the toughest undergraduate engineering exams in the world.

Speaking to The Better India, Hemant says the objective of the film is not to criticise or question the hard work students put into preparing for these exams, but whether they were given a choice at all and presented with all the possibilities available to them.

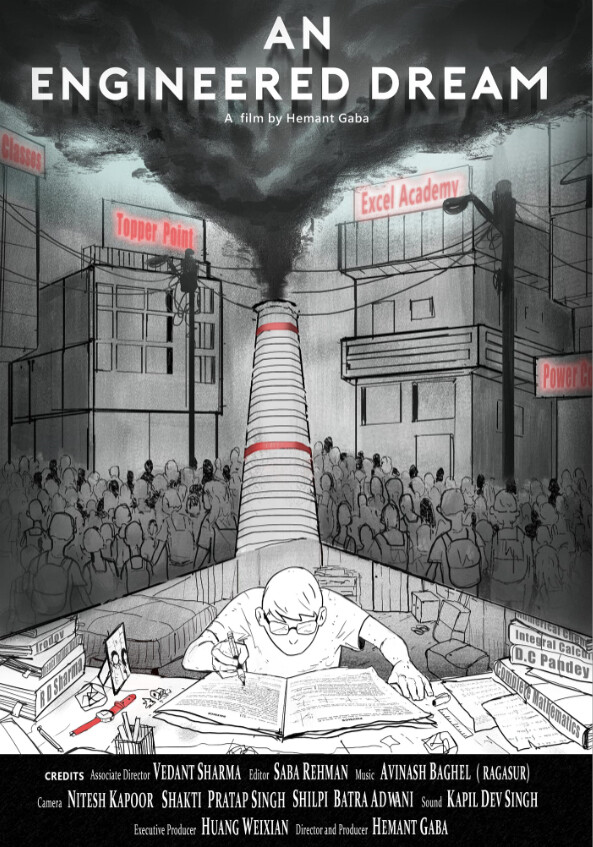

Is this their dream? Or is it a dream forced upon them by their parents? This is perhaps why Hemant chose the title ‘An Engineered Dream’ to highlight this discrepancy.

The Making Of

The process of making this documentary began almost by accident in 2016 when Hemant was approached by a Bollywood-based writer to direct a feature film based in Kota.

“He had pitched a fiction film idea based in Kota and I went to do some research on his behalf. Although I had never been to Kota before, I had heard about the coaching centres and intense pressure students go through while preparing for JEE. While conducting my research, I decided to simultaneously work towards making a documentary,” says Hemant.

After all, he had heard about an open call for human interest documentaries from the Asian Pitch. Launched in 2006, the Asian Pitch is backed by Asian public broadcasters willing to fund high-definition documentaries produced by Asian documentary makers. Initially, all Hemant had to do was create a trailer, write a treatment and synopsis, and submit it. Within three months, his first pitch came through and he soon received an invitation to deliver an in-person pitch in Taiwan. His documentary was chosen among nearly 140 other proposals.

“I first raised funds for the film in September 2016. With funding from Asian Pitch, the film was telecast by public broadcasters in Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan and Japan in 2018. By the following year, it was licensed to History TV 18 in India and the national broadcaster of China. Despite an original run time of 72 minutes, many of these broadcasters presented a shortened 48-minute version, which we had to make,” he says.

Meanwhile, to shoot this film, Hemant spoke to a variety of students across Kota for a year and even lived in a hostel room for two weeks with one of the four protagonists. A lot of work went into establishing a good relationship with these students to make them feel that they weren’t talking to hostile ‘outsiders’ or strangers. One of his editors even stayed with the family of a girl in Surat for a few days.

“Before shooting this documentary, we spoke to over 100 kids in Kota to finalise our four main characters. We needed to check whether they were comfortable speaking in front of a camera. We also had to obtain consent from students and their parents as well,” he says.

For an hour of raw footage, his team would often have to wait for two days. Along expected lines, however, not all hostels complied with Hemant’s request to shoot the documentary. He had to ask one of the students to shoot the footage himself in a style similar to vlogs.

Asking Difficult Questions

“Through the film, I was trying to ask some hard questions concerning the indoctrination that is passed on from one generation to another and how the pursuit of an engineering course at elite institutions in IITs is a part of it. Today, it’s engineering, but a couple of decades down the line when the profession is less in demand, something else might take its place. What remains is a herd mentality and the process of indoctrination around it imposed by families and the larger society. Children have no choice,” says the 41-year-old freelance filmmaker.

Hemant argues that in the course of interviewing so many parents and students, he realised that nearly all of them weren’t making an informed choice about sending young boys and girls to Kota, where they have no life beyond academics.

“A major motivation driving parents is the desire to see their child climb up the economic ladder. By sending their child to Kota, parents hope that it will result in admission into the IITs and eventually a couple of years later, a well-paying job. These parents feel that within one generation they can climb the economic ladder from lower middle class or middle class to upper middle class or higher. Of course, there is a desire to garner society’s respect in the process. As per my estimation, less than 5 per cent of students study in Kota out of any genuine love for science or engineering,” informs Hemant.

Most children who study there between the age of 15 and 17 aren’t even aware of the other academic or career options before them because their exposure is very limited, he observes.

“Students who come to Kota aren’t usually from big cities, where they have resources and coaching institutions to prepare them. Comparatively speaking, in smaller towns, students have less exposure and endure greater pressure from parents and society,” he adds.

Missing Out on Life

Most children in coaching classes don’t attend regular high school, while some go to Kota after it. It is hard not to observe that they are missing out on life.

“Those years are a major part of growing up. In the first sequence of the film, you can see a very famous ‘godman’ or ‘spiritual guru’ speaking at an event attended by 1 lakh students from different coaching centres. Sponsored by the coaching centres, who have brought him in a helicopter, even the chief minister of the state is in attendance. This ‘godman’ tells students not to focus on relationships, but on their studies. But children at that age [15-17] get into relationships and develop crushes. When children ask questions about feeling lonely in a place like Kota, he tells them to just focus on studying, a message reiterated by parents. How can these children branch out from all this pressure created at home and Kota,” he asks.

Loneliness is a major concern for students even though 150,000 students come to Kota every year. This problem is exacerbated by the intense pressure they are under. Some coaching centres bring in former JEE rank holders to meet the current batches and are absurdly showered with praise for not having other hobbies.

One of the most poignant moments in the documentary is when one of the students, who shot the footage by himself, prays to Donald Trump for starting a Third World War before the exam. He follows this by wondering out aloud the possibility of killing himself. Between 2013 and 2018, 77 students died by suicide in the city, as per government data.

Another major issue is claustrophobia, which Hemant witnessed first hand.

“While making the film, I took a room in one of the better hostels. It was a very small room without a window. Attached with a washroom, there was no daylight coming through. I lived there for about two weeks at a stretch and felt so claustrophobic. Mind you, I’m a well-adjusted adult, who has experienced many challenging circumstances. Living there, I wondered how a 16-year-old child leaving home for the first time in his life, who has never lived without his close family and friends, would feel in this room. Their life consists of sleeping, studying, eating and using the washroom and that cycle goes on,” he recalls.

Despite so many children living in these hostels, there is little to no socialising, which is looked down upon. Fortunately, children in Kota are now talking about loneliness.

There is another part of the documentary, where a gentleman who runs one of the bigger coaching institutes, tells students during an orientation session that they are not there to make friends. He says their personal lives don’t matter at all and that they’re there to take their parents out of their current economic situation to a better place.

Real Villains of The Piece

Though, not all children choose to endure the pressure of getting into IITs. There are few students who don’t want to be in Kota but they don’t have the courage to say no to their parents. Instead, they spend their time playing computer games, making memes, videos, watching porn, etc. This small minority knows that getting admission into an IIT is impossible.

“Before I went to Kota, I would hear the media cursing coaching institutions. But going there, I realised they weren’t the real villains. They are opportunists there to make money. The real villains are families and society who create pressure and foster a toxic environment for these children. These institutions are just catering to a particular demand. None of them are forcing people to come to their coaching institute in Kota. Families exercise an active choice to send their children there. Of course, many coaching institutes engage in sleazy practices, but ultimately it’s the parents’ choice. These institutes are unethical, but they use the same business practices many use to make more money,” says Hemant.

Helping These Students

It’s a sad commentary on Indian society that parents will continue sending their children to coaching institutes in Kota despite these harsh realities. This practise won’t stop in the near future. So, what can be done to alleviate their troubles?

Many coaching institutes have now instituted helplines for students suffering from mental health issues while others have in-house mental health professionals. The problem is that someone alone and severely depressed will not seek professional help.

In the documentary, the local district magistrate tells Hemant that his administration has been introducing a variety of extracurricular activities to take the stress off these children. Despite their best efforts, he admits that suicide rates haven’t dropped. After all, he admits that those who are severely depressed will not participate in such activities or seek help.

“Also, considering the number of students in these hostels attending coaching classes, it’s not logistically possible for each of them to get 30 minutes a week with a mental health professional. It’s a massive task. Coaching institutes can mitigate some of the problems students face there, but that’s not enough. The toxic environment there induces so much pressure. It’s a larger culture that has to be addressed. Governments and mediums of popular culture like movies, TV shows, web series or news media organisations will have to play a role in disseminating a message to parents living in small towns and cities that even chefs, musicians or athletes can enjoy a successful career. After all, it takes one successful generation to break out of the cycle of wanting their children to become a doctor, engineer, civil servant or any of the preferred career options today,” he says.

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

No comments:

Post a Comment