Many of us know the Chitale brand thanks to its shrikhand, yoghurt and other dairy products. The homegrown brand is also popular for their own variant of the Gujrati snack — ‘Bakarwadi’. A multi-crore business today, it all started when a ‘chance’ dairy farmer in Maharashtra’s hinterland turned his purchase of a few dozen buffalos back in 1939 into a booming business.

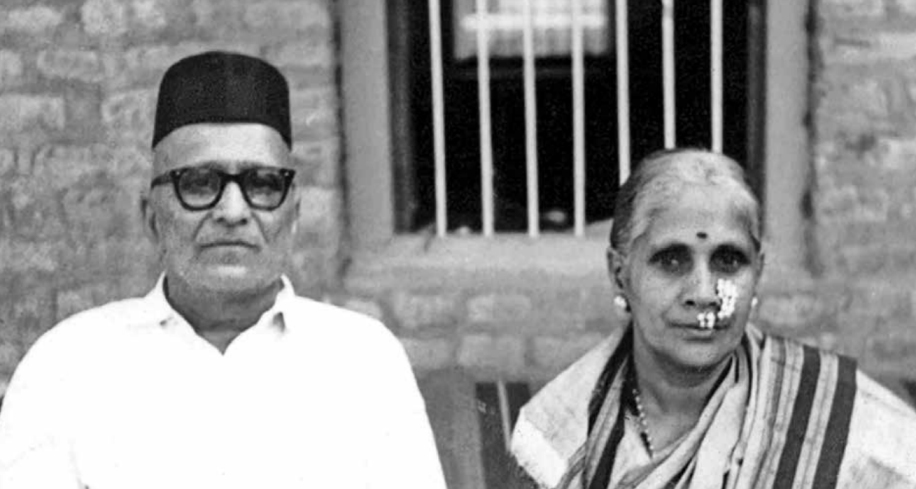

Bhaskar Ganesh Chitale, also known as Babasaheb, came from a long line of landlords and money lenders. But in the early 1900s, at the age of 14, when his father died, he dropped his studies to take care of his widowed mother by becoming a farm labourer in his drought-prone village of Limbgove, which was about 20 km from Satara.

After years of little to no success from toiling in the fields, Babasaheb grew anxious. He knew he had to supplement his income. In 1939, he took a train to Bhilawadi in Sangli district, which is where the story of Chitale begins.

In the beginning… there was milk

“Our dining table used to often convert into boardroom meetings over family lunches,” says Indraneel Chitale, great-grandson of Babasaheb, recalling his earliest orientation of his family’s dairy business. “We weren’t explicitly told about our legacy. But my grandfather, Narasinha, used to make it a point to take me with him to the factories or cattle sheds he was visiting.”

Indraneel, who joined the business about a decade ago, had a completely different initiation into his ancestors’ business. “My great grandfather had lost everything in the pandemic in 1918. Over the years, as he failed to supplement his income, he came across Bhilawadi. The village lies on the banks of the Krishna river, and from an agricultural point of view, it was a good place to start a business. The availability of water throughout the year and a railway line reaching Mumbai was his criteria for setting up the business there,” says the 32-year-old.

Bhilawadi was home to a large stock of domesticated animals, and the village was virtually swimming in excess milk produced because of the abundance of animal fodder. “The dairy business was set up in an era where there was no pasteurisation of milk or standardisation of its quality. Everything had to be sold fresh, or it had to be converted into other milk products such as curd or hung curd or khoa [condensed milk],” says Indraneel, adding that they were primarily a B2B supplier in the beginning. The products were supplied to Mumbai with the help of the British railways.

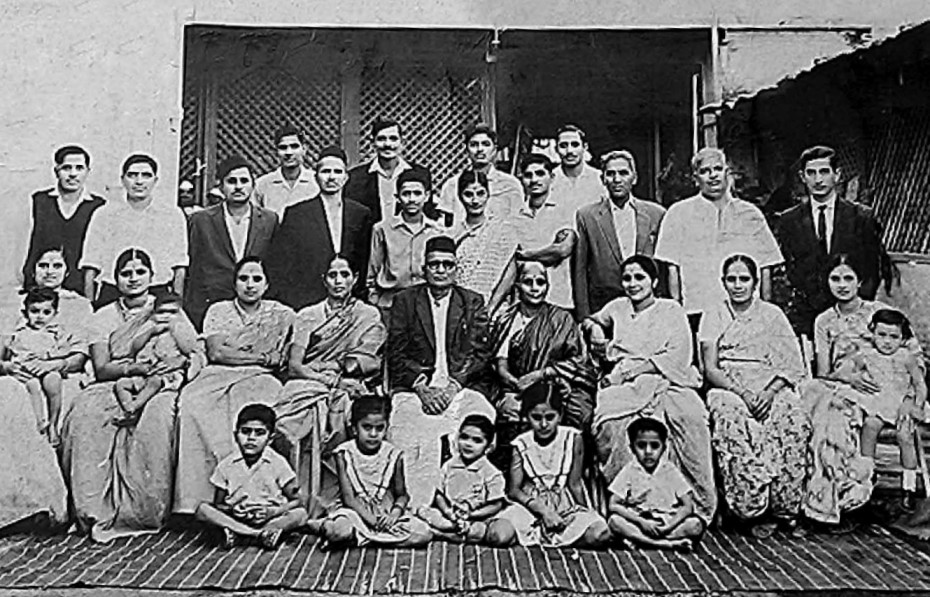

But keeping a check on the market grew cumbersome as there was no electricity or connectivity. That’s when Babasaheb roped in his eldest son, Raghunath Chitale, who was working in a mill in Surat, to start looking after the business in Mumbai.

“To be a milk supplier, you need a strong repeat consumer base, which Mumbai lacked at the time. So we shifted our base from Mumbai to Pune. In 1944, my grandfather, Narasinha—Raghunath Rao’s younger brother—joined the business,” he says. But there was another issue with being just a B2B supplier. “Retailers would claim the milk wasn’t fresh, and we couldn’t prove otherwise. This would result in a loss of payments. That’s how we started selling milk under our own brand,” says Indraneel.

Back in the day, Chitale was selling about 45 to 50 litres of product per day, says Indraneel, assuming they had around 20 cows. “We were only selling what we were producing. We had a 10,000 sq ft house and an adjoining cattle shed,” he adds.

In the mid-1950s, Raghunath’s other brothers, Parshuram and Dattaray, joined the business that now became the forte of the four Chitale brothers.

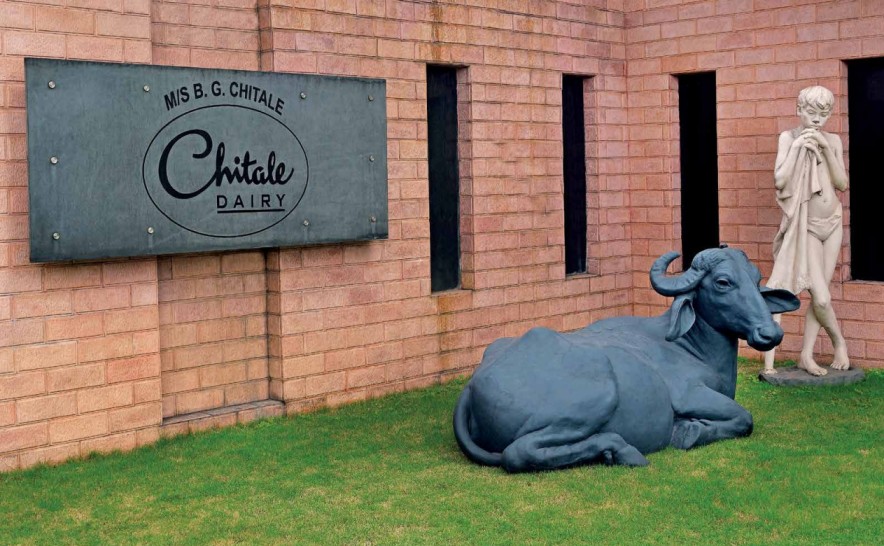

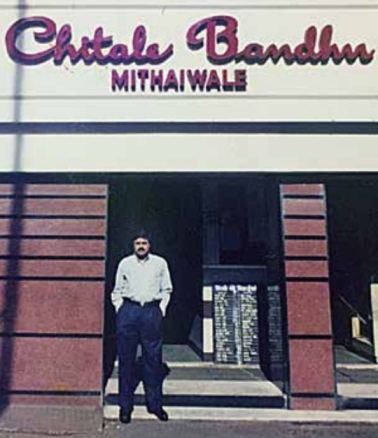

The Chitale dairy product business, which came about simply because of the lack of storage facilities for the excess milk produced, is now split into two businesses: Chitale Dairy and Chitale Bandhu Mithaiwale.

“Today, we process close to 8 lakh litres of milk every day, out of which we sell 4 lakh litres of liquid milk while the remaining is converted into condensed milk, hung curd, cottage cheese, shrikhand, ghee [clarified butter], cheese, milk powder, etc.,” says Indraneel.

Shrikhand, Stores & Streamlined processes

Living in the internet age, it is hard to imagine a time when personal feedback was quite literally something that was given in person. Sanjay Chitale, Indraneel’s father, says, “The brand, created by my father [Narasinha] and uncles, needed to be taken ahead. Without any website, Facebook, Instagram and social media, there was more customer interaction. We were like a family. People would come into our store with heaps of feedback which would help us a lot.”

Recalling an instance of their many travel accounts, Sanjay says, “Our shrikhand had a higher fat percentage than what was allowed. We had to go to Delhi to get permissions. Ram Naik, former railway minister, was a friend of my father who helped us a lot. He asked us to get the shrikhand to Delhi, where even Sushma Swaraj, the then health minister, had a taste and liked it. But I remember travelling all night to make the journey.”

Another major challenge was supplying a perishable product. “Our supply chain, the quality of the roads, packaging in glass bottles till the 1970s – were all a big hassle. Moreover, procuring raw milk from different avenues, processing it and supplying it to the markets by 4 am and then delivering it to the consumers by 7 am was all done by us,” says Indraneel.

Today, the brand also has collection centres up to 75 km from their dairy business. “About 40,000 farmers work with us. They supply their raw milk to these doodh sanghs [milk centres]. Every farmer supplies about 20 litres of milk,” says Indraneel.

“The retailers used to function on credit, and the farmer payments were infrequent. So, we had to find a way to manage the cash flow. So we opened stores (that sold milk and sweets) to help with the regular inflow of cash,” he adds.

To further streamline the process, the brand has now integrated technology like cloud computing, data analysis and automated payments to the farmers.

“There are also regular tests conducted to ensure no steroids or pesticide residue enter the final product. The market for liquid milk is limited to Mumbai and Pune. But our mithai market is worldwide. We have to comply with various regulations from different countries,” says Indraneel, adding that the brand completed 81 years in 2020.

The Bakarwadi

“Between 1980-95 was a crucial time for the brand,” says Sanjay, who joined the business in 1983. “We were a typical Maharashtrian brand at the time who wanted to reach out to other communities. So we had to develop products that were suitable for them too.”

Enter Bakarwadi — a Gujarati snack shown to Narasinha in the 70s by a neighbour who used to make a Nagpur variant of the same.

The besan and maida-based snack popularised by Chitale is an amalgamation of the flavour of two states. “The Nagpur variant is called ‘Pudachi Vadi’. This is an extremely spicy spring roll that is shallow fried. The Gujarati variant is also shallowly fried, but it has a lot of garlic and onion. My grandfather thought of combining the spiciness of the Nagpuri Pudachi Vadi and the shape of the Gujarati Bakarwadi and deep fry it for more crispiness,” says Indraneel.

The recipe, perfected by Narasinha’s elder sister-in-law, Vijaya, and wife, Mangala, went on sale in 1976. Soon, they couldn’t match the demand for their bakarwadi.

“Bakarwadi sales increased exponentially. The 100 people that we had hired to make the product were not enough to meet the demand, which is why we needed automated manufacturing,” says Sanjay.

He adds, “During 1992-96, I travelled a lot to research for the Bakarwadi machines. There was a lot of R&D required for the machines, and communication was only possible through the mail, which took a long time.”

“Today, we have three lines making Bakarwadi at nearly 1,000 kgs an hour,” says Indraneel, adding, “To get the same level of spiciness for Bakarwadi, we have specific breeds of green and red chilli cultivated.”

He further adds, “We also have our own fruit processing unit where we produce our own mango pulp, just to ensure there’s no deviation in the sourness or tanginess of its flavour. Mango pulp is one of the main ingredients in our shrikhand and mango burfi. This process ensures consistency in the mango pulp flavour throughout the year.”

Sanjay says, “Our gulab jamun mix is another popular hit with our customers. This was only possible because my mother, Mangala, and wife, Varsha, tried their hand at perfecting the recipe. We even gave demonstrations to different stores for this product.”

A household name

A company that started with the quintessential milk bottle delivery is now hopping onto the Keto-vegan bandwagon.

“With the internet, we are a lot better connected with our consumers across the world. Thanks to e-commerce, we can launch many products that might not work in conventional retail environments but will work very well in the online retail forum, like products with no added sugar, keto-friendly or vegan-friendly products,” says Indraneel.

And times have definitely changed from the 40s to now.

“We were the first company in the country to start packaging milk in pouches in 1971. Glass bottles were cumbersome to handle because of breakage, losses and recleaning the bottles,” he says, adding, “We could serve a larger customer base because of packaging in pouches.”

In 2003, the brand moved into the distribution chain business, where they went beyond their own stores to sell their products.

What started with 10 employees, four of whom were brothers, has now turned into an international brand with close to 2,000 employees.

Interestingly, the brand didn’t make use of any TV or radio commercials for this growth.

“Our word-of-mouth publicity was so good that we never required to advertise our products. TV only had Doordarshan, and newspaper ads were expensive, so we only resorted to that during festivals. It was only until the dawn of social media that we started aggressively advertising,” says Sanjay.

A testament to the brand itself, Chitale had to make no claims on any billboards or put up posters because their name is guarantee enough — you get the best they can offer, even 80 years since its inception.

(Edited by Vinayak Hegde)

No comments:

Post a Comment