Nothing deterred Jayantrao Salgaokar whose ‘doomed’ idea of making a panchang, or the Indian almanac system accessible to the common man by integrating it into a calendar, was ridiculed by society. He was ready to take the financial risk despite knowing that selling calendars was a bizarre idea as they were freely available in the 1970s.

Using all his astrology knowledge and printing expertise, the class 10 pass from Mumbai invested a sum of Rs 2,600 and made copies of his calendar in 1973. With an unperturbed attitude and resolute belief, he went to vendors to sell his calendars. No one gave him an advance but he foresaw a revolution in India’s calendar system.

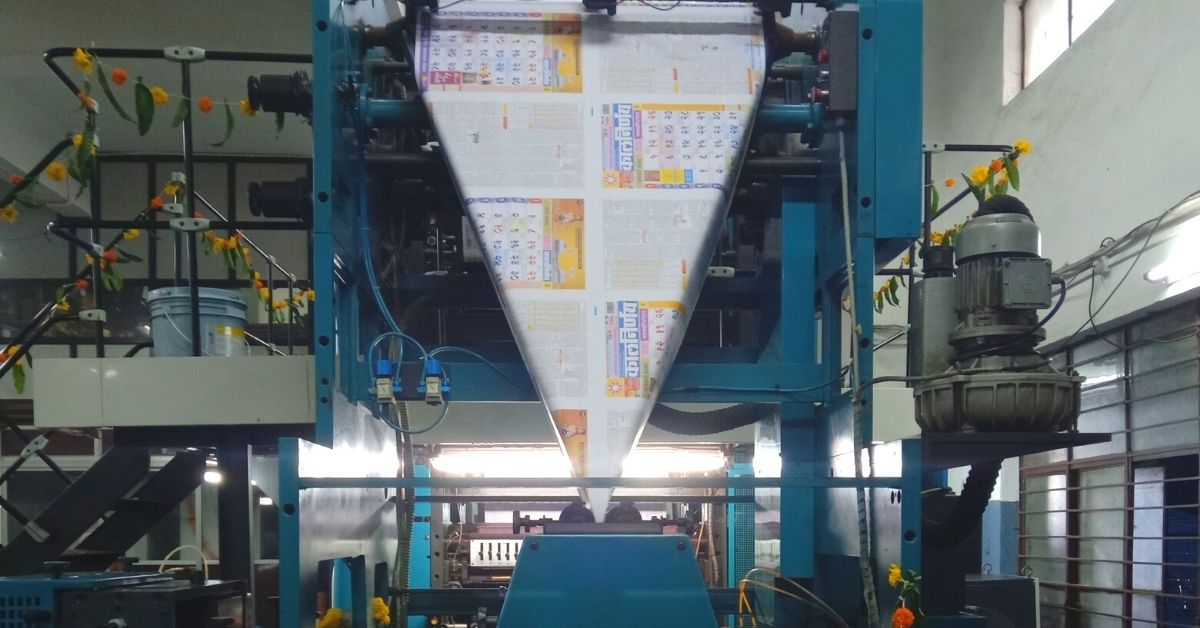

Fast forward to 2021, 1.8 crore households across India use Jayantrao’s ‘Kalnirnay’ calendars that are available in nine languages — Marathi, English, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Malayalam, Punjabi, Tamil and Telugu.

What makes this Kalnirnay stand out, apart from it being the largest publication in the world, is its multi-purpose and all-inclusive component. Homemakers, farmers, students to butcher shops, everyone finds a use in these calendars. In 1996, the braille edition was also introduced.

In Nashik’s Nitnaware household, Archana, a mother of two, uses it to mark the auspicious days in the months, upcoming festivals and fasting dates. This helps her prepare food in advance. She also circles the dates when her milkman and domestic help don’t turn up. Meanwhile, her husband, Dilip marks birthdates of relatives in red-coloured ink and her daughter loves reading health-related articles that appear on the reverse.

The Maharashtrian family has been using Kalnirnay for over 30 years, and even today, they prefer this over smartphones. They haven’t found an unparalleled alternative to Kalrniyays.

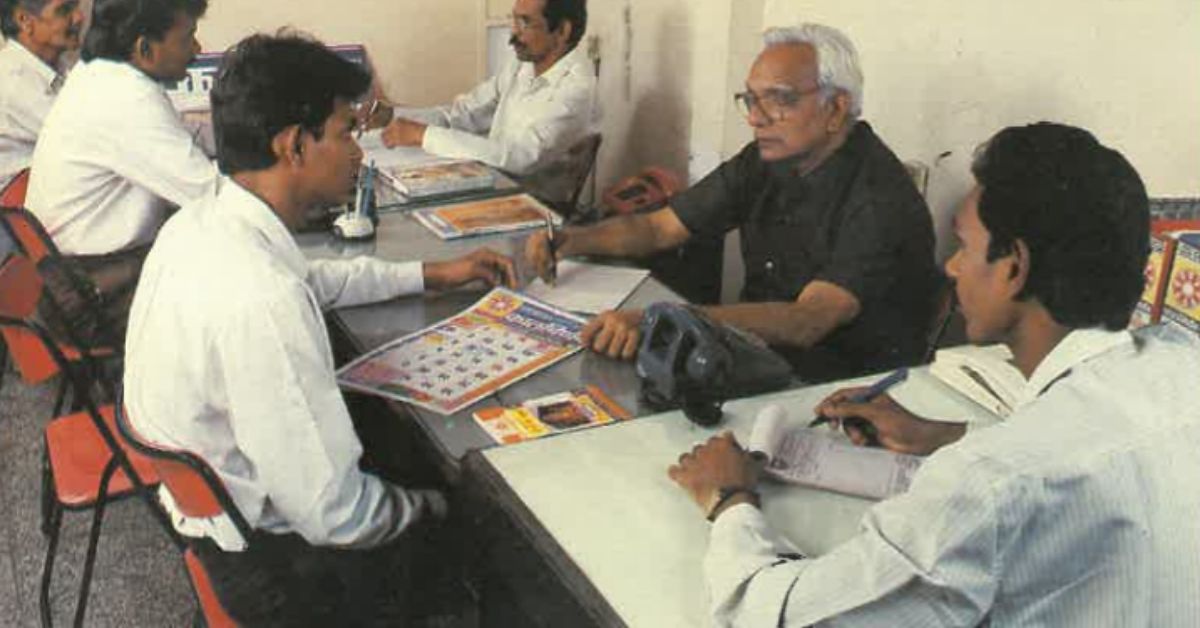

“Whether it is buying a bike, moving to a new house or a job, investing money, deciding a newborn’s name or welcoming a bride, Indians make important life decisions according to auspicious dates. My father knew the significance of the almanac but he saw only pandits or the brahmin community had a monopoly to decipher its Sanskrit texts. Mentioning auspicious hours and minutes in the calendar may not be a big deal today but nobody was doing it back then. That’s why Kalnirnay (Kal+time; Nirnay=Decision) took off,” Jayaraj, Jayantrao’s son and the managing director of the company tells The Better India.

If launching Kalnirnay was a daunting task, equally challenging was its sustenance through the decades, not to forget the advent of the internet. The calendar could have easily become obsolete but the Salgaonkar family used technology and innovations to keep it going.

Jayaraj and his daughter, Shakti, a third-generation entrant, take us through the history of Kalnirnay that is more than a calendar. It could make an impressive case study in business schools — a man who dared to break away from ancient monopolised practices while retaining the essence of panchang with modern solutions.

Simplifying a 2000-year-old system

Jayantrao worked as a crossword compiler with Loksaktta, a regional newspaper, and dabbled in an unsuccessful lottery business before starting Kalnirnay. Friendly relations with journalists helped him spread the word around.

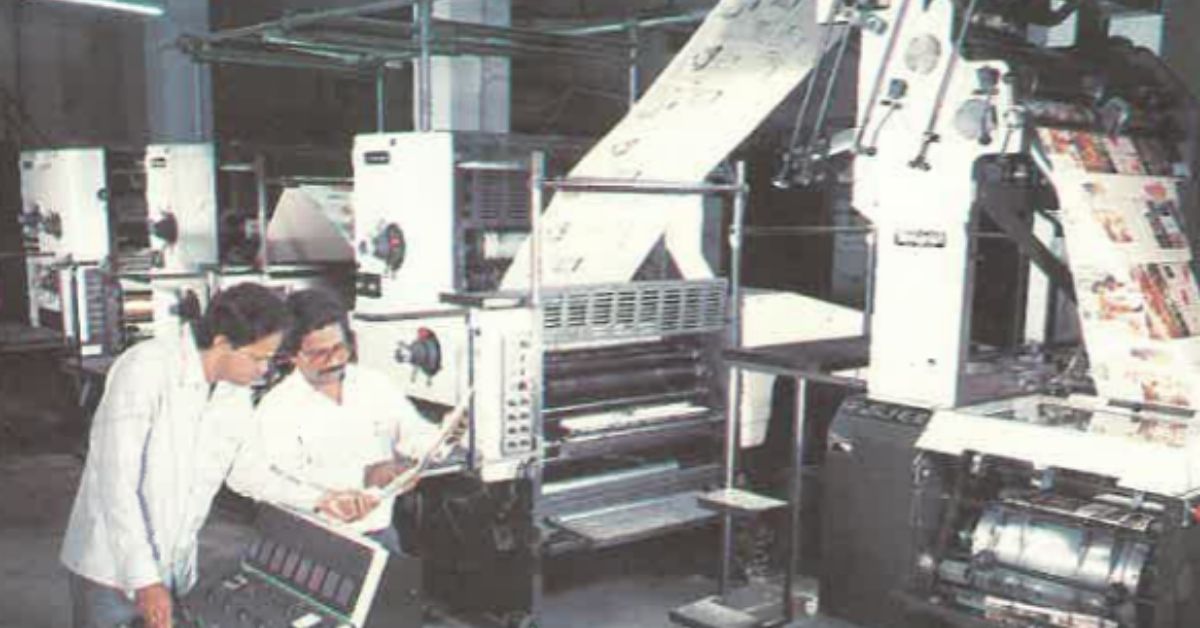

According to Jayantrao, the company was the first one to hire a typographer and get colouring scanners in the state in the ’70s. Besides the content, the founders were very particular about the quality of paper which is exposed in the air for a month before it goes for printing. They designed special machines to make punches in the paper and prevent it from tearing. A patented colour is used for the ribbon by which the calendar hangs on the wall.

He began with five people who did everything from designing, printing to distribution. Kalnirnay was an amalgamation of the Gregorian and Indian calendars. To make it more engaging he added more pages to include forecasts, literary articles, recipes and so on.

“Panchang in Sanskrit means ‘five limbs’ — Tithi, Nakshatra, Rāśi, Yoga, and Karana. The almanac measures time and marks intervals called ghatika and pali between the five limbs. The scholars convert these divisions into hours and minutes. The system, which is 2,000-years-old, was simplified to the level of a class 8 student. However, just dates didn’t fill the pages so my father decided to add recipes and articles,” says Jayaraj, who was only 17 when the venture started. He soon became the editor and arranged for noted writers like Durga Bhagwat and PL Deshpande for the articles.

The father-son duo went from one vendor to another, leaving samples of calendars and agreed to forego the unsold calendars’ payments. When the initial sales didn’t occur as per plan, Jayantrao approached his journalist friends to write reviews which later boosted sales. He also got advertisers to market their brand for the masthead.

“We sold 25,000 copies in the second year in 1974, and today we sell more than 1.5 crores annually. For every edition, our team, which has now risen to 150 people, thoroughly researches contents for months to create a mini-encyclopedia-like calendar. We don’t promote any religion or give unsolicited advice,” says Jayaraj.

How Kalnirnay became a household name

Every year, the calendar is released on the first day of Navratri and they begin work for the next year immediately after. For months, the team conducts surveys among people to know what they would like in the calendar. They incorporate the latest trends as well.

Jayaraj recalls one particular incident when a professor gave them the idea of marking the important occasion in colours or with symbols. He says, “In the ’80s I was visiting a professor and I saw him marking the shravan (fasting) dates in yellow colour. Now, we symbolise the days with a warkari flag. In another instance, a newspaper boy inspired the idea of our famous jingle ‘Kalnirnay ghya na’ [take kalnirnay, please]. Our website was introduced in 1996 after Indians living abroad mentioned they also wanted the calendars delivered. It garnered hundreds of responses from NRIs across the world in the first month of our launch.”

However, listening to people and incorporating changes accordingly hasn’t always worked in their favour. They have faced several lawsuits over the years. One man had filed a case against the company as he was upset by the inclusion of a chicken recipe in the calendar that was hung right next to his home temple.

The Salgaonkars have used the calendar’s credibility to educate people about social taboos and issues as well. In one of the 1980 editions, they had written about adulterated formula milk and how breast milk is the best for infants. Another year they debunked myths around Aids. Recently, they wrote about mental health.

“We include everything that people are interested in, from health, insurance scams, organic farming to nutrition. When the digital boom happened, we were quick to launch an application and website. Many people told us the internet would replace calendars but we were a step ahead,” says Shakti, who joined in 2016.

They used social media platforms to their advantage and connected with customers directly, answered the queries and took their feedback. They kept the website simplified, and most importantly, accurate. The team regularly sends updates of clutter-free content on their handles.

Both Jayaraj and Shakti have strenuously evolved the company year after year with their innovative solutions. The annual growth rate of their revenue stands between 10-12% and last year they churned a revenue of Rs 50,00,00,000 despite the pandemic.

“COVID-19 is probably the most difficult phase in our company’s history but we found a way to work from home and each of our employees gave their 100% to ensure we released the calendars on time. And we did. Our last year’s learnings are already helping us work on 2022 calendars in full swing. We won’t disappoint our customers because for them Kalnirnay is not a product, it is an emotion,” adds Shakti.

Jayantrao, who passed away in 2013, made sure Jayaraj and Shakti inherited his positive spirit, leaving no room for dejections even in the most difficult times like the pandemic.

Edited by Yoshita Rao

No comments:

Post a Comment