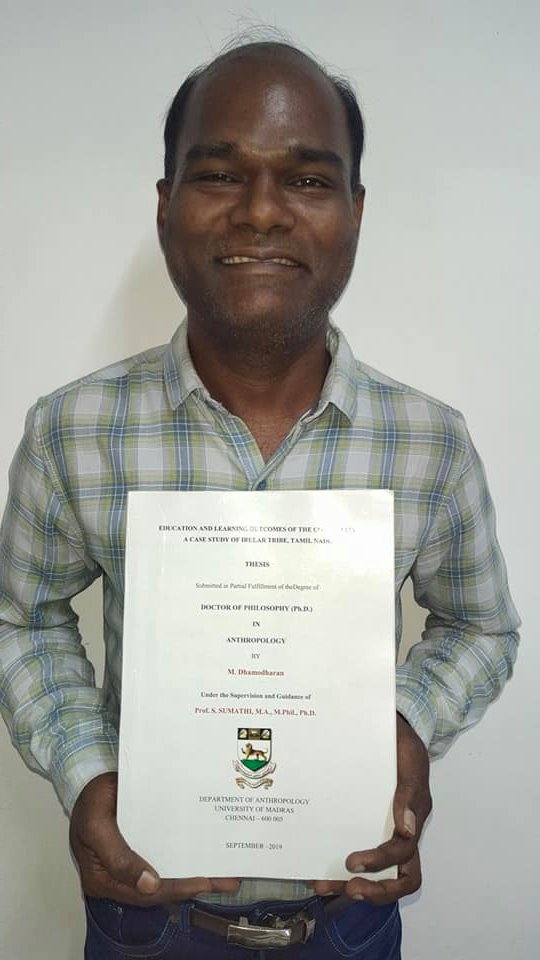

On 30 March, Dhamodharan Muniyan, a 41-year-old former child labourer from the Adi Dravidar Scheduled Caste community, defended his PhD thesis on improving the learning outcomes of children from the much-maligned and deprived Irular tribe in Tamil Nadu— one of India’s oldest indigenous communities. They are found in the states of Kerala, Andhra Pradesh (Chittoor), Tamil Nadu (northeastern) and Karnataka.

In these 41 years, this son of agricultural labourers from Kachirayapalayam Colony village in Kallakurichi district, Tamil Nadu, has lived many lifetimes and overcome impossible odds.

Earlier this week, The Better India caught up with the newly minted Dr Dhamodharan to discuss his incredible life story and his groundbreaking research on educating Irular children.

Hard-Knock Life

Growing up in Kachirayapalayam Colony, Dhamodharan recalls a life stricken by poverty.

“Living in a mud house with no land to our name, my family struggled to have three square meals a day. We were surviving on rava (coarse flour) and a few bags of rice that my parents would get from landowners as payment. Sometimes, we would get sambhar or some sort of curry from kind neighbours. My father, Muniyan, and mother, Nagammal, worked as agricultural labourers earning barely Rs 12 a day each. Despite studying in a local middle school, by the time I was 10, I had to join my mother at work because my father was suffering from a debilitating illness and couldn’t do hard labour. From Class V onwards, I was helping my mother support the family. We would work on the fields of other landowners doing weeding and cultivating paddy, besides cleaning local ponds. In a year, I would miss nearly three months of school—one month at a stretch and the other two intermittently—to support my family, which included my two younger brothers,” says Dhamodharan.

For Muniyan, the dream was to see Dhamodharan finish high school and get a simple government job because he never earned more than Rs 1,000 a month. Unfortunately, with no scope for studying before or after school and participating in extracurricular activities, he had his troubles. Dhamodharan failed his Class 10 mathematics exam. “My father was very angry with me, saying he would rather spend money on a buffalo which would give the family some milk and income instead of my education. This really upset me,” he recalls.

Failing to clear his class 10 exam meant working to support the family. Job opportunities, however, were restricted to working on sugarcane and paddy fields and brick kilns in Kerala. For six to seven months every year from October to May, about 80 residents from his village would take a lorry to Salem, from where they would travel in unreserved train compartments to work in the brick kilns of Veliyathunadu village near Aluva town in Kerala. After coming back home, Dhamodharan would find work in paddy and sugarcane fields.

Working like this for two years, he was resigned to the fact that this would be his life. On his travels to Kerala and at home, he would see children going to school and that would intermittently rekindle his desire to study again. However, it was his mother, Nagammal, who pushed her son to continue his education. Finally, after three more attempts, he passed his class 10 exam. Nagammal would further help him re-enrol at a nearby school run by the state’s tribal welfare department, despite Muniyan’s strong reservations.

“My father rejected my request to finish high school and told me to focus on earning since I was the eldest son at home. It was my mother who pushed me towards studying further. She helped me enrol for class 11 and 12 even though our neighbours and relatives criticised the move saying things like — ‘Learning is not for you’, ‘Why are you wasting your family’s money’. My father’s friends too criticised him for sending me to school, but I immersed myself completely into academics and passed class 12 in my first attempt,” he recalls.

Tragically, the happiness of graduating high school was short-lived after his mother passed away following an accident that occurred as she was taking the cows out to graze. The responsibility of taking care of his ailing father and two brothers fell on his shoulders. Every morning, he would cook for the family and then work as a farm labourer.

“Despite my compulsions, I was desperate for higher education. Discussing the matter with my younger brothers, I asked them whether they would take up the mantle of cooking and earning for the family. They decided to give up their studies, while my father took a loan of Rs 10,000 to help me enrol into college in Chennai,” he says.

Finding His Purpose in Chennai

Dhamodharan applied for a BSc in Botany at The New College in Royapettah, Chennai. Although the college had no hostel facilities at the time, he had a friend who got him to share a small room for Rs 600 per month in a slum behind the Tidel IT park in Taramani. At the turn of the century, he was finally in Chennai and pursuing his goal of higher education.

“In the same year, I met Dr Balaji Sampath, an educationist, social activist and founder of AID INDIA, a Chennai-based non-profit working on ensuring access to basic healthcare, livelihood education for low-income families. At the time, Dr Balaji and AID INDIA volunteers from IIT-Madras were conducting after-school learning programmes for children in Taramani slum. These were children who came from similar backgrounds like mine. Impressed by their work, I too volunteered to organise these after school programmes after my college classes ended at 1.30 pm. Meeting Dr Balaji changed my life forever,” says Dhamodharan.

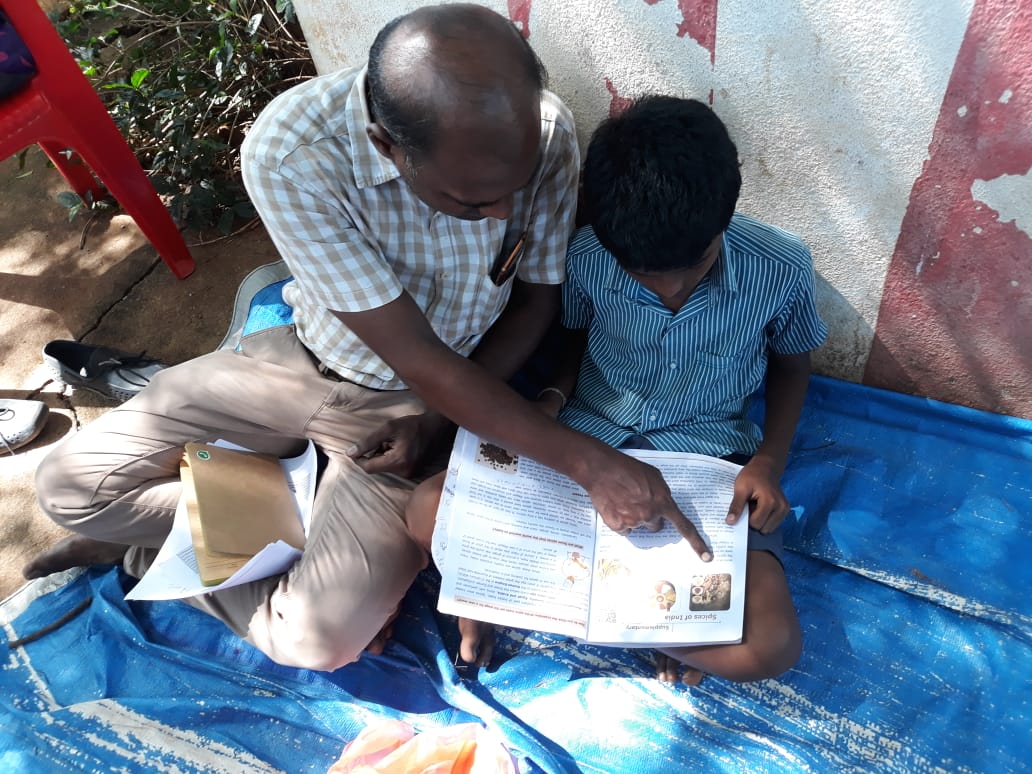

Upon joining as a volunteer, Dhamodharan and his friend started other learning hubs for slum children in the area, identifying qualified local volunteers to help teach them. However, as he got more immersed in his volunteering work, he wondered why children from the slums were struggling to learn. Working alongside Dr Sampath, AID INDIA volunteers and conducting extensive research, he developed language learning and teaching tool kits.

Meanwhile, he also began volunteering to teach science at local Chennai corporation middle schools with much prodding from Dr Balaji. This, he believes, gave him the necessary confidence to develop his own language learning tool kit.

“We initially did trial runs in the Taramani and other slum areas, and over time developed a robust language learning tool kit. Most children coming to these after school learning programmes study in government schools. Our objective was to create an impact on the government school system. We then approached the State government’s education department and established a close partnership. From 2006 to 2010, we worked with thousands of government schools. I gave math and reading development training to about 10,000 government school teachers. However, with the transfer of every government officer, there was no sustained effort on the part of the State,” he recalls.

After completing his BSc in Botany, he did his Master’s in Anthropology, following which he applied for an MPhil in Tamil reading skills from Madras University. Throughout this endeavour, AID INDIA paid for his college fees, and in a couple of years, he began working there full time.

Working on a variety of educational programmes with the state government took him to the outskirts of the city, where he first encountered children from the Irular tribal community. What he found was that the children living in ramshackle hamlets on the outskirts of Chennai were struggling to learn. When he decided to apply for a PhD at Madras University, he decided to dedicate his research towards understanding why these children were struggling and what could be done to ameliorate the situation.

Empowering the Irular Community

“The word ‘Irular’ [is] derived from the Tamil word called ‘Iru’ which means ‘darkness’. ‘Irular’ means those who are in darkness,” notes a paper published in the Indian Journal of Applied Research.

“There are 36 identified tribal communities in Tamil Nadu. Irulars form the second largest tribal group in the state, but their socio-economic living conditions have been marked by poverty, illiteracy (54% literacy) and an absence of social and economic security. The highest education they usually get on an average is up to class 9 with little support from their families to study further. Moreover, they suffer severe structural discrimination in government schools both from teachers and children from other communities,” notes Dhamodharan.

“Whenever I would visit these hamlets outside Chennai, I would compare the fate of these children to my own childhood. However, at least my home had a permanent roof and mud walls. These children were living in homes with old sarees used as walls and dated political party banners as makeshift roofs. During the monsoon, when the mud floor got wet, they would sleep on logs of dry wood. After my PhD commenced in 2013, I spoke to Dr Balaji, and asked whether AID INDIA could do something to improve their living condition. Since our education initiative with government schools in the city wasn’t paying genuine dividends for all stakeholders, we decided to focus on their lives in villages,” he recalls.

After much discussion and deliberation, the non-profit began an initiative to construct pucca homes for the poorest families from Irular, Adi Dravida and other backward communities.

Till today, they have built over 480 homes across nearly 120 villages starting from Thiruvallur, Kancheepuram and Cuddalore districts with each home costing about Rs 1.5 lakh to 1.8 lakh to build under AID INDIA’s Eureka Homes initiative. They even rebuilt homes for families who had lost their homes during the massive Chennai floods in 2015. As age old practitioners of hunting wild animals and fishing, communities like the Irular often settled on forest land or near water bodies, and thus denied land deeds (pattas) by the state.

Another fundamental challenge facing the Irular community is the total absence of pre-primary education for children. Dhamodharan remembers visiting a village called Cherukkanur in Thiruvallur District where we saw a child playing with the legs of a dead rat.

Pre-primary education from 0 to 6 years of age is one of the most crucial phases in the cognitive development of the child. He claims that 60% of their life skills are developed in this period. Unfortunately, the Irular community has no access to study material and the concept of pre-primary education is non-existent. So, when they enter the formal school system, they are already at a disadvantage and steadily lose their confidence to learn.

“These children believe that they are not interested in studies, but what they lack is proper intervention. Most of them come also from troubled homes, where they suffer abuse, hunger and homelessness. They lack the proper pre-primary education required to develop their cognitive skills. Without this, once they enter the formal school system, they lack the confidence to learn. Neither their parents nor schools encourage them to study. I remember this child, Rasathy, who dropped out after she turned 11. Her teacher said that she was better off rearing pigs than going to school. So, she began working at a water park nearby and the last time I met her, she was 17 with a three-year-old child,” he recalls.

He also remembers how 89 out of the 134 students from class 1 to 8 students whom he interviewed from 2016 to 2018 had dropped out of school within a year of the survey. Majority of those who dropped out were from class 5 to 8.

To address these issues, AID INDIA has organised multiple toy distribution drives for Irular children at the pre-primary level, organised peer-to-peer learning sessions and even provided tablets for them. On these tablets, students study using an e-learning app called AhaGuru started by Dhamodharan’s wife, Gomathi S and Dr. Balaji. Having said that, he knows this is not enough and what these children need is continuous intervention.

“Our goal is to ensure these students stay in school, receive special attention and learn. Our intervention cannot stop until they get a respectable job and earn a steady income although you’ll only see a genuine difference two or three generations down the line,” he says.

With his PhD complete, Dhamodharan is not contemplating a career in just teaching.

“I want to help underprivileged children on the ground. Once this pandemic abates, I will travel to these settlements often since these days I only get to go there once a month,” he says, adding, “My plans include building a vocational training centre for school dropouts from the Irular community, who are predominantly agricultural labourers and brick kilns workers, and a dedicated residential hostel.”

Dr Balaji, meanwhile, has nothing but praise for him.

“Damu (Dr. Dhamodharan)’s passion to use education technology to reach and educate the poorest children is amazing to see. He leads all of AID INDIA’s education programs and is currently using the AhaGuru app to educate over 74,000 poor children in remote villages in Maths, English and Tamil. Moreover, he studied the education status of Irular Tribal communities and his thesis was greatly appreciated by both Indian and foreign examiners. Most importantly, Damu’s thesis is not just a theoretical study, he has been directly applying his research findings to improve the quality of learning for Irular children as well as other tribal and dalit children in so many villages,” he says.

Dhamodharan adds, “Education is the only tool for social advancement for people like me. My brothers continue to work in brick kilns, but I’m supporting their children’s education.”

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

No comments:

Post a Comment