Decades ago, when author and diplomat John Zubrzycki was working in India, he came across the famous ‘Hindu basket trick’ at a crowded railway station. In this trick, a young boy or girl is put inside a wicker basket, which is then pierced with swords. The swords are then removed, and the young boy/girl remerges, completely unharmed.

This, and several other magic tricks, have been picked up by western magicians from India, as early as the 1800s. Snake charmers, levitation, rope tricks, juggling — you name it. Most of these tricks find their origins in India, taken abroad by white-skinned folks to be popularised with their own tricks and twists. But in return, up until the 1950s-60s, all India received in exchange for giving the world some tricks up its sleeve was the notion that “Indian magic” was one that promoted occultism and black magic.

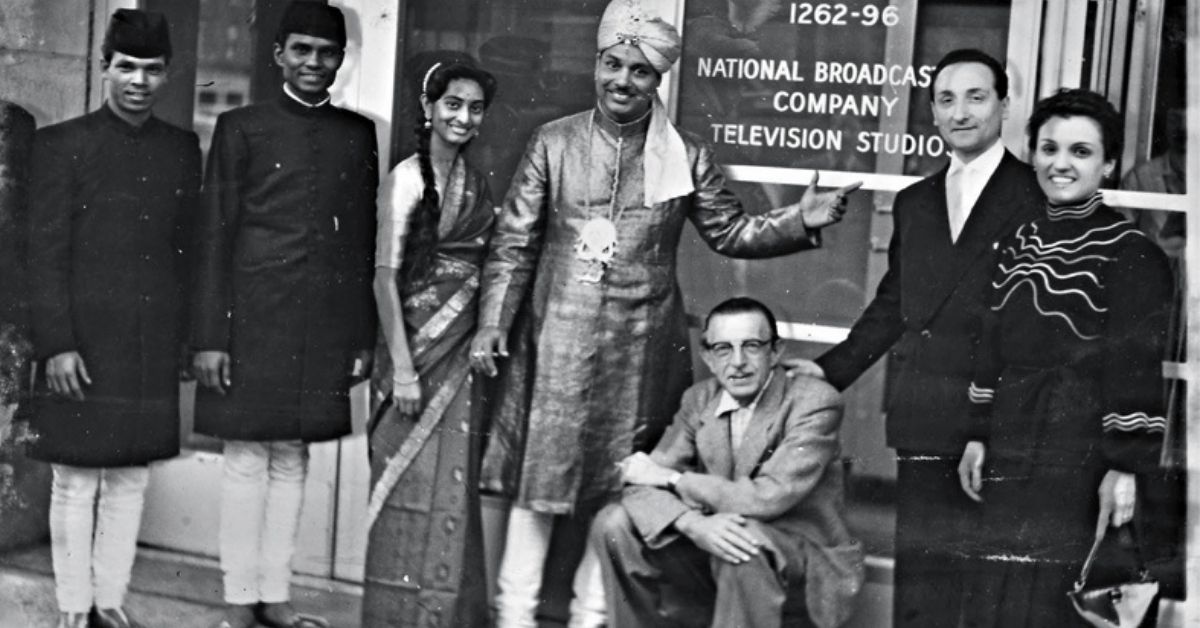

However, one man can be credited with changing these perceptions of the western audience. He did so cleverly, keeping in mind the West’s strange obsession and fascination with ‘exoticism’, yet introducing them to a side of India they had perhaps not seen before. This was no street magician or snake charmer — he travelled with elaborate stage props, a large team of assistants and helpers, and all the equipment one might need for grandeur and pomp and show.

Today, this man has gone down in history as the ‘father of modern Indian magic’, and rightfully so.

A new India for the West

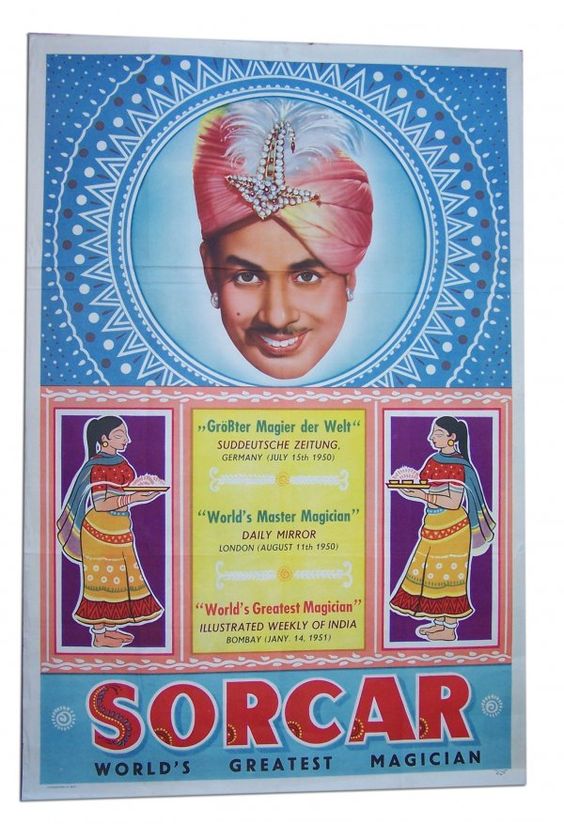

Protul Chandra Sarkar was born in 1913 in a small village in what is now Bangladesh. Growing up, he was always drawn to the world of magic and illusion. He was a mathematical prodigy, and yet, found magic to be his true calling. He began his career by performing in circuses and theatres and eventually trained under magician Ganapati Chakroborty. Some time during his career, he changed the spelling of his surname to ‘Sorcar’, which sounded close to ‘sorcery’.

Sorcar’s breakthrough in the UK and Japan came at a time when India was viewed only as a once-regal country that was now an impoverished colony, attempting to slowly get back on its feet. The imagery of half-naked men, fakirs, broken English, snake charmers, poor people and cows was shattered by the way Sorcar presented himself to the audiences. There was no fakiri around this man, who dressed like he was royalty or perhaps a character that had stepped straight out of the Arabian Nights. When he spoke to his audiences, he did so with a clear and distinct “Indian accent”, but in a tone that was inviting and friendly, and left a sense that something otherworldly was going to take place that night.

Through his show Indrajaal, or The Magic of India, Sorcar captivated audiences with tricks he identified with his homeland. Some of these included the Temple of Benaras, which was a variation of the Hindu basket trick, The Water of India, Floating Lady, and X-Ray Vision. The Water of India involved a bucket filled to the brim with water, which Sorcar would empty from time to time, only for the audiences to find it filled to the same volume every time.

His most sensational trick, of course, remains the one where he slices his young assistant in half.

A ‘murder’ in the streets

When Zubrzycki saw the Hindu basket trick at the railway station all those years ago, his experience was marred by a tragic conclusion. When the boy emerged from his wicker basket, he did so with a knife in his neck. Clearly, there was no trickery or illusion involved here.

In the 50s, Sorcar did something similar. Or did he?

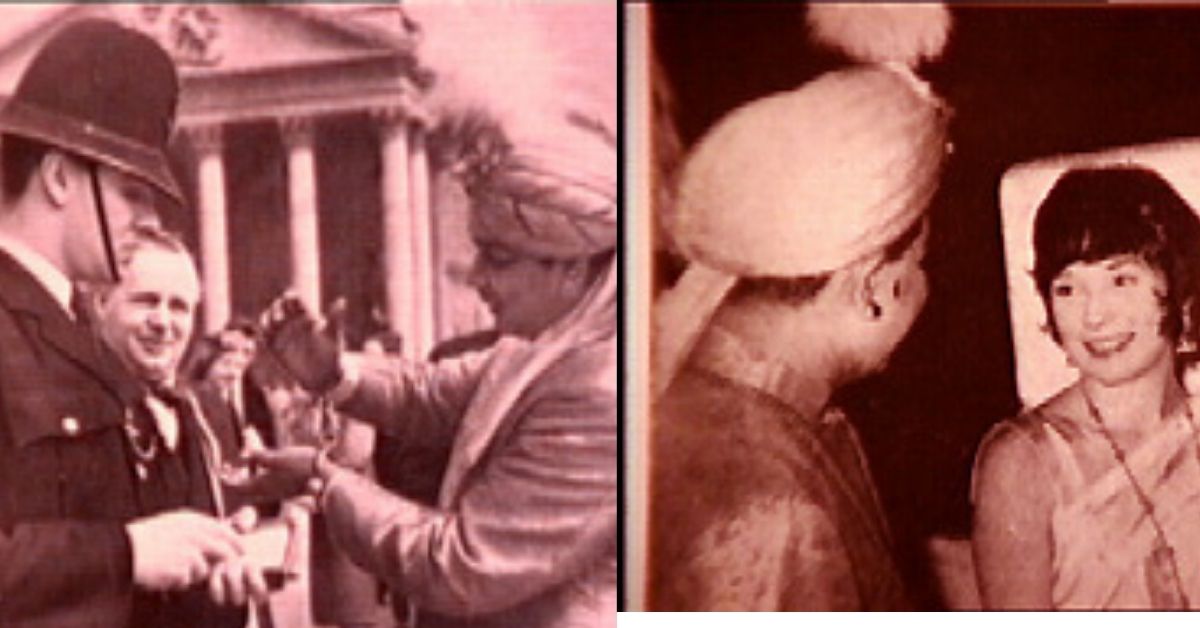

Back then, BBC’s popular investigative journalism series, Panorama, was only a few years old, but already a hit. On 9 April 1956, the show decided to deviate from its usual serious reportage to give a 15-minute segment to Sorcar. Here, he performed his famous sawing trick.

In every performance of this trick, Sorcar would slice his assistant, 17-year-old Deepti Dey, without putting her in a box first. So her body would be openly sliced, for the audience to see. Before the trick, he would hypnotise her into a trance, and after he was done cutting through her, like you would a slab of meat, he would bring her out of her stupor and make her stand before the audience to show that she was, in fact, alive and unharmed.

On this 9 April night, the trick should have gone down the same way. Sorcar hypnotised Dey once she had laid down on the bed with a menacing looking circular saw hovering over her. Slowly, and steadily, the saw, now in full motion, was lowered to her body, and the audience was engaged in a slow torture of sorts, watching it slowly slice through her body. The machine was then switched off, lifted, and Sorcar called for Dey to wake up. She didn’t.

Immediately, broadcaster Richard Dimbleby stepped in front of the camera, and announced that the programme was over. The studio’s phone lines were flooded with concerned calls by viewers across the nation, panicked that a young girl had just been killed on live television.

The show’s official explanation for abruptly cutting the programme off was that Sorcar had extended the time provided to him. However, for those privy to Sorcar’s penchant for realistic illusions, it was obvious that what had taken place that night was the ultimate sleight of hand. He was far too smart to have simply let his time run out. Everything had been planned.

The next day, headlines across the UK spoke of the alarming event that had unfolded the night before, and how an innocent girl had been killed for the world to see. They were immediately assured that Dey was, in fact, alive and well. Sorcar’s popularity skyrocketed, even more so than what he had already established. The rest of his season in London saw nothing but sold out tickets and audiences were enthralled by the man who had taken them for such a joyride.

Throughout his career, Sorcar travelled the world as India’s cultural ambassador. China, Australia, Japan, Russia, and the US — wherever he went, auditoriums and theatres were jam packed. He performed for American troops during the World War, and wrote detailed columns in magic magazines. His first show in Japan was 1932, organised by Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose, who was working with the Japanese to raise money for India’s freedom movement. The show was nothing short of a hit. In 1950, he performed at a convention of the International Brotherhood of Magicians and the Society of American Magicians in Chicago. He won the prestigious Sphinx Award for Magic—considered comparable to the Nobel Prize in the industry—twice, once in 1946 and again in 1954. In 1964, he was awarded the Padma Shri by the Government of India.

Of course, Sorcar’s soaring popularity did not sit well with all his contemporaries. In 1955, Helmut Ewald Schreiber, who was also Adolf Hitler’s favourite magician, accused Sorcar of stealing his tricks. But many magicians in the field rallied with Sorcar instead, reminding Schreiber that he had appropriated an Oriental stage name — Kalanag. He had tried to hide his nationality and had stolen the tricks he was accusing Sorcar of copying.

By the 70s, Sorcar’s health had started deteriorating. In January 1971, having ignored his doctor’s advice and flown to Japan, he was performing his Indrajaal show, which would be his last. As he left the stage after his performance, he suffered a severe heart attack and passed away. His future generations have carried forward his legacy, with all of them and their kids being involved in the field of magic. Noted Indian magicians P C Sorcar Junior and P C Sorcar Young are the magician’s sons. Sorcar also has two daughters, Ila and Geeta.

Despite his fame and glory, Sorcar was viewed as something of an outsider. But he was also instrumental in taking India’s magic to the world and enthralling western audiences with tricks from his homeland. This year, as a tribute to his 50th death anniversary, his eldest son, Indian American artist and animator Manick Sorcar, wrote that his father had two sides to his personality.

“At home, he was a simple man that took care of his family — particularly me and my four siblings — with whom he played, laughed, joked, and yet, he was still a strict father, making sure we paid full attention to our education and schoolwork,” he wrote, adding, “The other was the Great P C Sorcar, whom the world knew as the great magician…on stage he wore the trademark glamorous costume — the bright sherwani, jewellry, lockets, glittering earrings, and a pagri (turban) with gems and plume, as the ‘Maharaja of Magic’, hypnotising the whole world with his illusions, elaborate stage settings, and dozens of assistants and musicians.”

In his book about his father, P C Sorcar: The Maharaja Of Magic, published in 2018, P C Sorcar Junior perfectly encapsulated the impact that Sorcar Senior’s legacy had on audiences across the world. “Even after my father’s body was flown in from Japan…people gathered outside our house at night, expecting him to return, much like he would at the end of his disappearing tricks, appearing from a distant corner with the shout ‘I am here!’.”

Edited by Yoshita Rao

No comments:

Post a Comment