At Dyer’s command, those Gurkha troops

Gathered in a formation tight, my friends.

Under the tyrant’s orders, they opened fire

Straight into innocent hearts, my friends.

And fire and fire and fire they did

Some thousands of bullets were shot, my friends.

Like searing hail they felled our youth

A tempest not seen before, my friends.

Riddled chests and bodies slid to the ground

Each one a target large, my friends.

Haunting cries for help did rend the sky

Smoke rose from smouldering guns, my friends.

Just a sip of water was all they sought

Valiant youth lay dying in the dust, my friends.

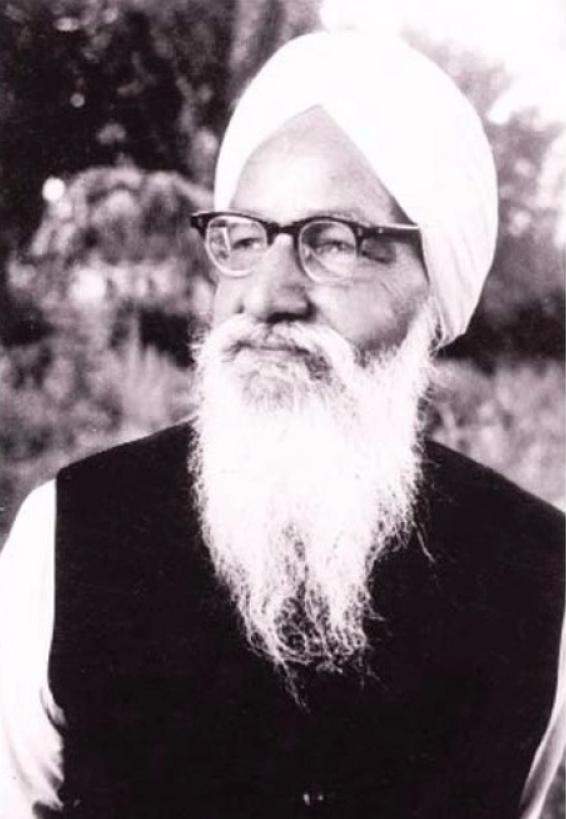

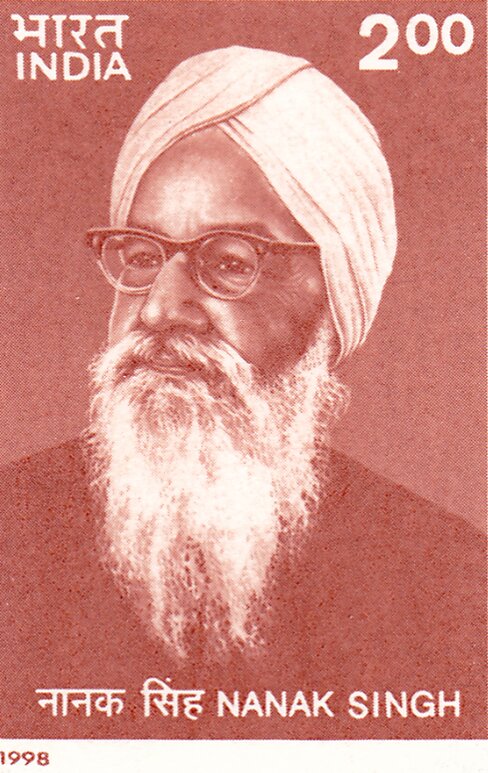

Nanak Singh, a literary giant and ‘Father of the Punjabi Novel’, was present at Jallianwala Bagh on 13 April 1919. Barely 22 at the time, Nanak Singh witnessed General Reginald Dyer’s troops open indiscriminate fire on unarmed civilians protesting against the draconian Rowlatt Act and the arrest of popular freedom fighters Saifuddin Kitchlew and Dr Satyapal.

(Image above of Nanak Singh receiving the Sahitya Akademi award from President S Radhakrishnan in 1962.)

Unlike the hundreds who were slaughtered that fateful day in Amritsar, Nanak Singh survived the massacre. He had collapsed in a stampede triggered by the firing and was left for dead under a pile of corpses. The two friends with whom he had attended the protest died. Nanak Singh suffered hearing damage in his left ear and walked out of Jallianwala Bagh after arising from the pile of corpses hours later when he regained consciousness.

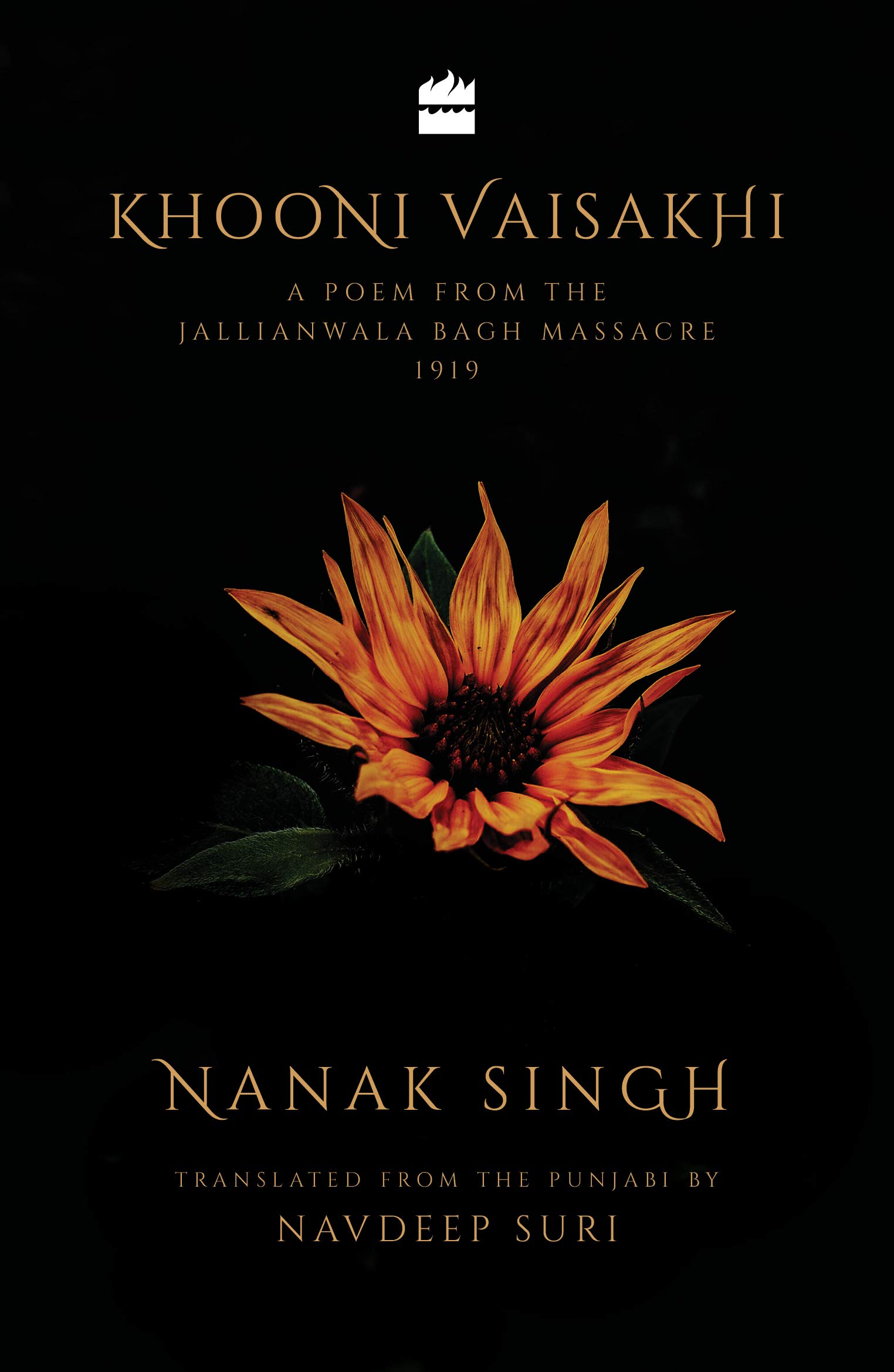

Nanak Singh’s long Punjabi poem, ‘Khooni Vaisakhi’, which runs for more than 4,000 words, describes in vivid, poignant and accurate detail the events leading up to the horrors of 13 April, its immediate aftermath and captures the mood of Amritsar.

The poem, a scathing critique of the British Empire and its actions on the day, was banned days after its publication on 30 May 1920. Following its ban, the poem was lost to the world for six decades until it was rediscovered and published again in November 1980.

On the Jallianwala Bagh massacre centenary, Navdeep Suri, a distinguished diplomat and Nanak Singh’s grandson, presented an English translation of the poem and a collection of essays compiled into a book published by HarperCollins India.

A day before the 102nd anniversary, The Better India spoke to Navdeep Suri to discuss the process of translating the poem and his grandfather’s remarkable life and legacy.

Being True to the Soul of the Poem

By all accounts, Nanak Singh lived a remarkable life. Born on 4 July 1897 in Chak Hamid, a small hamlet five hours away from Multan in present-day Pakistan, he was the oldest of four children. Given the name Hans Raj by his parents Bahadur Chand Suri and Lachchmi Devi, he spent his initial years in Peshawar. In the city, his father ran a modest trading shop.

With formal education only upto Class 4, Hans Raj was forced to run the shop when he was barely 10 after his father died of pneumonia. Despite the rigours of supporting his family, Hans Raj developed a real passion for music and poetry. He was only 12 when an eight-page booklet of his verses was published in 1909 under the title ‘Sehrafi Hans Raj’.

Six years later, his life would change after meeting Giani Bagh Singh, a scholarly figure in the local gurdwara, following which he converted to Sikhism and took the name Nanak Singh. His first major encounter with organised politics came with the Akali Movement or the Gurdwara Reform Movement and the struggle for Indian Independence in the early 1920s.

Sent to prison for participating in ‘unlawful’ political activities, he would soon find his calling there, which was to write novels seeking to reform society and make India a better place. His nearly five-decade prolific career as a novelist would witness him write dozens of short stories and 50 books in the longhand Gurmukhi script like ‘Pavitra Paapi’ (Saintly Sinner) in 1945 and ‘Ik Mian Do Talwaran’ (One Sheath and Two Swords) in 1959, which won him the Sahitya Akademi Award—India’s highest literary honour—three years later.

Barely 11 days after the end of the 1971 India-Pakistan War, he passed away on 28 December (age 74) at his home in Preetnagar village, a few kilometres outside Amritsar.

In the larger context of his storied literary career, the poem ‘Khooni Vaisakhi’ was barely a blip. But its relevance to the larger narrative of the freedom struggle and the lessons it holds for today’s generations cannot be ignored. That is why Navdeep took on the challenge of translating it into English so that it could reach a much wider audience than Punjab. A remarkable feature of the translation is how Navdeep stayed true to the poem’s rhyme and metre.

“Before Khooni Vaisakhi, I had translated two of my grandfather’s novels. Poetry, however, was a different kettle of fish altogether. Initially, I felt that I was not upto the task. Everyone suggested that I translate this poem in free verse, which gives you greater flexibility in conveying the exact meaning of what the poet is trying to say. Initially, I tried this approach on a couple of passages, but it didn’t gel,” says Navdeep, speaking to The Better India.

Taking inspiration from Douglas Hofstadter, an American linguist and cognitive scientist, and his book ‘Le Ton Beau De Marot: In Praise Of The Music Of Language’, he decided to stick with the fundamentals of rhyme and metre while translating his grandfather’s poem.

“Rhyme and meter place a constraint on the writer since the choice of words available are very narrow. So, why should the translator be exempt from those constraints? Moreover, Indian poetry is meant to be read aloud. In the process of translation, if you miss out on integral facets like every second line rhyming, I think you commit some violence on the soul of the poem. Once you make that decision to stick with rhyme and meter, your own sense of inventiveness doesn’t go away because your endeavour is to be true to the original, but also make it readable and bring some elegance to the translation,” he explains.

A real challenge, however, was the final part of the poem, which contains ‘letters of anguish’ that the common people wrote to the British government following the massacre. In these ‘letters’, which Nanak Singh converts to verse, the people lament the horror brought upon them with the massacre despite doing so much for the British Empire, like sacrificing thousands of their young men in the First World War.

If literally translated from the original Punjabi poem, these would read as ‘letters of anguish’. But there aren’t many English words that rhyme with ‘anguish’. After struggling for days, Navdeep came upon ‘postcards of pain’ for ‘letters of pain’. There are a lot of words that can rhyme with the word ‘pain’. Note the example below:

Sir Rowlatt came out of the blue,

His Bill got passed, none had a clue

And troubles came like a flood of rain,

Our postcards of pain

O’Dwyer singed the terrible law,

A heap of misery is all we saw

Only those butchers stood to gain.

Our postcards of pain

And then it was Dyer’s turn

To light a match and let it burn,

Fired bullets at us with such disdain,

Our postcards of pain.

Lost and Found

The British government banned the poem after its publication in May 1920, and all copies were confiscated, destroyed, and subsequently lost. Nanak Singh references the poem in his autobiography in 1949, but only in passing.

Navdeep’s father, Kulwant Singh, a leading publisher in Punjabi who had translated many of Nanak Singh’s novels, was desperate to find an original copy of the poem. In the years following his father’s demise, Kulwant had approached Giani Zail Singh, a leading politician from Punjab who served as chief minister anVaisakhi80 became Union home minister in Indira Gandhi’s cabinet to find the poem. After all, Giani was a big fan of Nanak Singh’s novels and even attended his funeral. But the process of finding the poem had failed to produce any results.

Meanwhile, Dr Kishan Singh Gupta, then a lecturer in Punjabi at DAV College in Hoshiarpur and another fan of Nanak Singh’s writings, had stumbled upon an original copy of Khooni Vaisakhi in an old collection of books his grandfather had left behind in gunnysacks stored away in the family home containing books and pamphlets. As someone who had taught Nanak Singh’s novels for years, Dr Gupta found an exquisite poem he knew nothing about.

The discovery prompted Dr Gupta to write a paper titled ‘Nanak Singh’s Khooni Vaisakhi’ that was published in Jagrity, a literary magazine, in August 1980. The article was probably the first to focus on Nanak Singh as a poet. Kulwant Singh, who did not know Dr Gupta, discovered the article and was intrigued by the detailed references to Khooni Visakhi.

Within a few weeks of establishing contact, Kulwant worked out arrangements with Dr Gupta to publish Khooni Vaisakhi, complete with a detailed foreword and glossary. As they were working on publishing the poem, a large envelope arrived at Kulwant’s home in Amritsar bearing “a sheaf of photo-copied A4 papers that carried the full text of Khooni Vaisakhi, but minus the original cover,” from the Ministry of Home Affairs writes Navdeep in his book ‘Khooni Vaisakhi: A Poem From The Jallianwala Bagh Massacre 1919’.

Giani had finally delivered on his request to locate the poem.

“We had no idea where the book was found. Perhaps in some government archive in Delhi, we surmised. Or maybe from the Indian Office Library in London. The British had the reputation of keeping a record of everything. It would be a delicious irony that they helped us find a book that had been banned by them,” Navdeep goes on to write.

More importantly, the text of the photocopied pages from Delhi matched perfectly with what Dr Gupta had produced.

Finding Meaning

While translating the book, four things struck Navdeep.

1) Here was a 22-year-old who survived the massacre, writing about the event and recording it for posterity. There are several references in the poem where he talks about remembering the martyrs and their sacrifices. For example, there is a section about Jallianwala Bagh’s martyrs towards the end of the poem.

Writing the poem in 1920, he laments that almost a year had gone by since the event, and there was no memorial or shrine built to remember those who lost their lives. Only three decades later was an actual memorial constructed for the martyrs.

2) The second thing that struck him was his grandfather’s courage. This was when the Rowlatt Act was in force, which allowed authorities to arrest anyone for criticizing the British establishment. Yet, in his chapter on Dyer, Nanak Singh calls him a murderer. Back then, it took a lot of courage to say those words about the ruling dispensation.

3) “During the course of my research, I was curious to understand whether this poem was historically accurate or was poetic license heavily used. I found that the poem offers an accurate chronology of events and the mood of Amritsar city and its people. While historians will look at documents like the Hunter Commission report and come to their conclusions, what Nanak Singh does as a poet was capture the mood,” says Navdeep.

4) “Many in Punjab have been conditioned by the trauma of the Partition. The trauma and sheer intensity of the bloodshed in 1947 leads one to believe in deep-rooted communal enmity. But in his description of the Ram Navami celebrations that took place four days before the massacre, my grandfather talks about the spirit of communal amity between Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs. There are many references to it throughout the poem, “ he says.

Hindus and Muslims they gathered together

To rejoice at a festival, O my friends.

Brotherhood conveyed by Muslims that day

Beyond incredible it was, my friends.

A festival of Hindus though it was

Muslims made it just their own, my friends.

‘Tis hard to describe this feeling new

A miracle, it truly seemed, my friends.

Nanak Singh also references how Hindu, Muslims and Sikhs were celebrating the same festival together, how members of these religious communities were drinking water out of the same cup and eating food off the same plate. He goes on to describe the funeral processions after the massacre and how Hindu, Muslims and Sikhs walked side by side.

Should The British Apologise?

In the past few years, there has been a growing clamour by many Indians that the British government should apologise for the massacre. Navdeep, however, offers a more nuanced perspective on whether the British government should apologise.

As a global imperial power through the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, the British had much to answer for across the world. As egregious as the Jallianwala Bagh massacre was, there were other events and incidents in other former colonies like Kenya and Ghana, which also merit an apology. Where do apologies start, and where do they end?

“It’s understandable for Indians to expect an apology. But an apology is only meaningful if it comes from the heart to express a degree of remorse. There’s no point in trying to wring out an apology from a reluctant entity. That would be a meaningless exercise, in my view. A more effective proposition would be to help students in British schools learn about events like the Jallianwala Bagh massacre. This would mean introducing a more nuanced understanding of British imperial history instead of merely glorifying it in their education system,” he says.

More than an apology, what are our lessons and takeaways from the event as Indians? It has been two years since the centenary, and the Jallianwala Bagh renovation project, which was supposed to be completed two years back, remains unfinished.

“There is also something deeper we should reflect upon. The massacre occurred because we had an imperial power who had no remorse about ‘teaching Indians a lesson’. But the massacre also occurred because people were protesting against the Rowlatt Act, which allowed authorities to imprison people without trial. These provisions were built on draconian British sedition laws that continue to exist in our statute books 100 years later to suppress dissent. It’s okay to blame the British for imposing draconian laws, but have we done a lot better? An apology from the British for the massacre would be nice if they are actually contrite about it, but I think we should use an occasion like this to introspect,” he says.

(Edited by Vinayak Hegde)

No comments:

Post a Comment