In a significant development earlier this week, Indian pharmaceutical giant Cipla Ltd lowered the price of its generic version of Remdesivir—an antiviral drug originally made by US biopharmaceutical giant Gilead Sciences Inc—called Cipremi to Rs 3,000 from Rs 4,000.

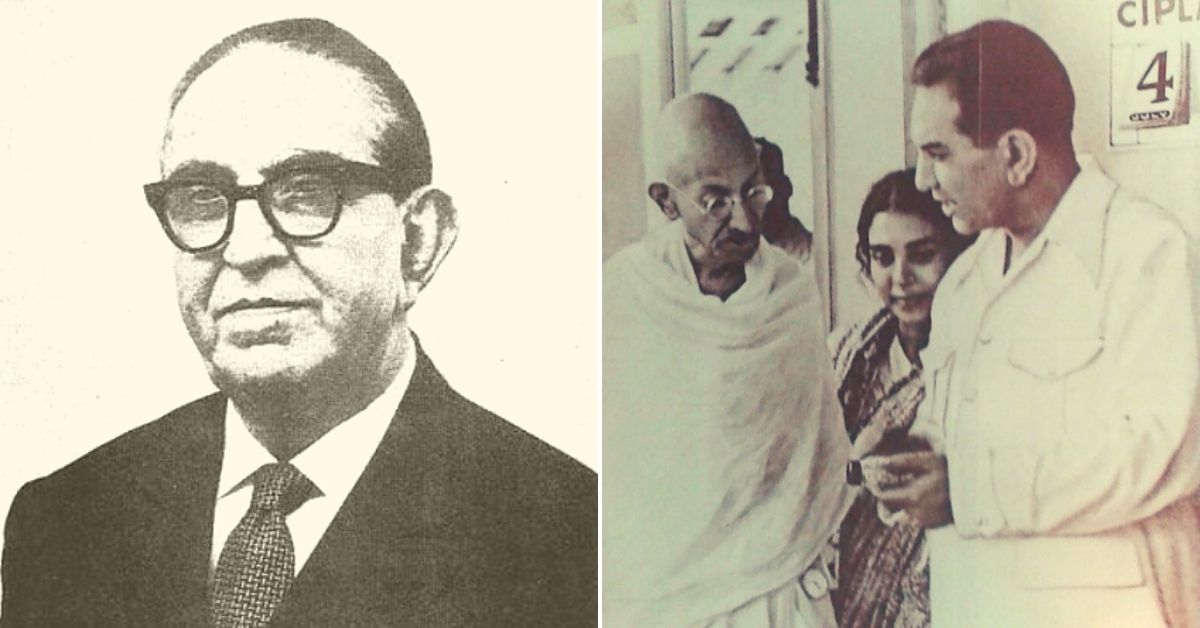

(Image above of Yusuf Hamied receiving Padma Bhushan from President Abdul Kalam courtesy Cipla Archives.)

This is part of a move by seven drug manufacturers in India to engage in a ‘voluntary’ price reduction at the behest of the Indian government. Intravenously administered, the Remdesivir, which comes in vials of 100 mg, is considered a key antiviral drug in the fight against COVID-19, especially in adult patients with severe complications.

This is what Cipla, a company founded in 1935 by Khwaja Abdul (KA) Hamied following Mahatma Gandhi’s call to make affordable drugs available to India’s poorest citizens, has been doing for years.

The company has been manufacturing generic drugs and supplying them at affordable prices amid different public health crises, including HIV/AIDS in the early 2000s.

KA Hamied set up Cipla to make India “self-reliant in healthcare”, pioneered in API (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient) manufacturing and played a pivotal role in the enactment of the New Patent Law, which allowed Indian pharmaceuticals to manufacture patented products as long as the process of manufacturing them was changed.

“This enabled Indian companies for the first time to manufacture any medicines and make them available and affordable for all Indians,” says Cipla on their website.

However, it was his son, Yusuf K Hamied, who turned around a company with an annual turnover of Rs 16 million at the time of KA Hamied’s death in 1972 to a market cap of Rs 680 billion today. Additionally, the company has over the years challenged the monopoly of Western pharmaceutical giants (Big Pharma) which have used patent laws to price critical medicines out of the hands of the most vulnerable.

Secular Upbringing

Born on 15 July 1936 to KA Hamied, an Indian Muslim freedom fighter and scientist from Aligarh, and Luba Derczanska, a Jewish communist from the erstwhile Russian Poland, in Vilinius, Lithuania, Yusuf grew up in a deeply secular household. A month after Yusuf was born, he was taken to Bombay (Mumbai) by his parents. It was the last visit they made to Luba’s hometown before the Nazi Holocaust killed her elderly parents in 1941.

Hamied had met Luba in Berlin on a lake cruise in 1925, while studying there. The couple soon fell in love and got married three years later. Before leaving for Germany, Hamied worked closely with leaders of the freedom struggle like MK Gandhi and Zakir Hussain and taught at Jamia Millia Islamia. Following his return to India, he founded a successful business venture called the Chemical, Industrial and Pharmaceutical Laboratories (Cipla) in 1935.

“It [Cipla] carried on as a small enterprise until 1939 when, with a new war looming, imports from Europe, particularly medicines, were suddenly curtailed. At this point, on 4 July 1939, Gandhi came to Bombay to ask Hamied to fill the gap. It was thus that his firm came to produce affordable medicines for the war effort, which after the war expanded to include the ‘third world’ as well,” notes Gerdien Jonker on KA Hamied’s early years in Berlin.

Growing up through the early years of Independence, Yusuf saw his father taking on entities like the Muslim League for propagating the two-nation theory and fighting for Hindu-Muslim unity despite the carnage surrounding Partition. Meanwhile, he studied in some of Bombay’s best schools and went on to earn a PhD in chemistry from Cambridge University before returning to India in the early 1960s to work in his father’s company.

Speaking to journalist Shrabonti Bagchi of the Mint earlier this year, Yusuf recalled not being treated as a ‘leader-in-waiting’, but as a common employee by the company.

“In the beginning, I remember cleaning the floors in the tablet department. It took two years for me to even get employment in Cipla, because I was related to a director. The board of directors was very strict. So for one-and-a-half years, I worked almost as a trainee with no salary, with a PhD degree, cleaning the floors. So what I decided was, I would learn the pharma industry backwards. Nobody will know more about the industry than I do, and that’s exactly what I did. I learnt how to make tablets, I learnt how to make injections…I did just about everything,” Yusuf said.

When Hamied passed away in 1972 after a brief illness, Yusuf took over the reins.

Boss of Generic Drugs

Years before Yusuf took on the mantle of challenging Big Pharma, KA Hamied wrote about it for The Times of India on 11 December 1964. Hamied argued that “patent law should enforce ‘compulsory licensing’ to other manufacturers to prevent monopolistic predatory pricing”, according to a 2016 Quartz India article.

To the uninitiated, “compulsory licenses are authorisations given to a third-party by the Controller General to make, use or sell a particular product or use a particular process which has been patented, without the need of the permission of the patent owner”, notes this explainer on Mondaq.

“Later, Yusuf picked up this same battle in the case of the astronomical pricing of AIDS medications by patent holders. By retro-engineering the first medication and antiretroviral cocktail effective against HIV and AIDS and selling them at a fraction of the price, he helped save millions of lives,” the Quartz India article goes on to add.

In the early noughties, Cipla made its name on the global stage by pioneering cheap access to antiretrovirals (ARVs) at less than a ‘Dollar a Day’ or $ 300 per HIV/AIDS patient per year from $ 12,000 per patient per year.

Before this announcement, Yusuf had warned the European Commission on AIDS in September 2000 that his company would break Big Pharma’s monopoly on life-saving drugs needed to treat this fatal disease and ensure they were accessible to those who needed them the most.

Writing a profile of Yusuf in 2003 for The Guardian, journalist Sarah Boseley called him the “generic drugs boss”. “The assumption that AIDS drugs were not for the poor—that they could not afford them and therefore that there was no point even thinking about ways to get people treated—was blown out of the water,” wrote Sarah at the time.

“Now, in the post-Hamied era, the genie will not go back in the bottle. The big drug companies have been forced to drop their prices for these new and powerful drugs and offer them to a market they had no interest in developing—the impoverished African states where a whole generation of parents, teachers and workers are dying,” she added.

Hans Lofgren, in his book ‘The Politics of the Pharmaceutical Industry and Access to Medicine’, talks about how Yusuf played an influential role in the pioneering development of multidrug combination pills (also known as fixed-dose combinations, or FDCs), for other ailments like tuberculosis (TB), asthma and others that largely affect low-income countries. The book goes on to talk about his role in the “development of paediatric formulations of drugs, especially those benefiting children in poor settings”.

Yusuf’s challenge to Big Pharma, however, didn’t go unanswered. In 2005, Parliament passed the Indian Patents (Amendment) Act, which came following the government’s decision to sign the World Trade Organisation (WTO) Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). This piece of legislation set up real barriers for Indian pharma companies from producing generic drugs through reverse engineering.

Despite setbacks in 2005, Cipla went on the path of “incremental innovation”.

“The pharma industry is growing by leaps and bounds, and we also have to go that route, but what India also requires is what I call ‘appropriate technology’, technology that is suited to our country and our needs, and which is summed up in two words: incremental innovation,” he told Mint.

He adds: “How do you repurpose drugs? How do you reposition them? I will give you an example — there is a drug called ivermectin, which was used to treat parasite infections, and now it is being used for treating COVID-19. That’s called repurposing and repositioning, and this is the area in which India could take the lead. I am not saying we halt innovation, but we are better off today with incremental innovation rather than concept innovation.”

For his yeoman service to the developing world, the Indian government awarded him the Padma Bhushan in 2005. Eight years later in February 2013, Yusuf announced his retirement from Cipla after serving decades as the company’s managing director.

Since his retirement in 2011, however, Cipla has gone through its share of controversies, particularly related to drug overpricing with cases listed in the Supreme Court.

For example, earlier this year, the national drug pricing watchdog, the National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority, created a list of companies accused of overcharging customers. “According to the list, Mumbai-based Cipla has to pay the maximum penalty, over Rs 3,000 crore (including interest but minus the sum recovered),” notes this report in The Print.

Earlier this month, the Chhattisgarh government was considering legal action against the company for not meeting its supply requirements for Remdesivir.

But despite the controversies, the legacy Yusuf leaves behind is largely positive. Today, his niece Samina Hamied serves as Executive Vice Chairman while Umang Vohra is the company’s Managing Director and Global CEO. Yusuf is the company’s chairman, and given his age (84), he is not involved in the day-to-day running of the company.

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

No comments:

Post a Comment