Michael John Carritt, an officer of the erstwhile Indian Civil Service (ICS), was by his own account a ‘double agent’ working for the British colonial government and the Indian freedom struggle.

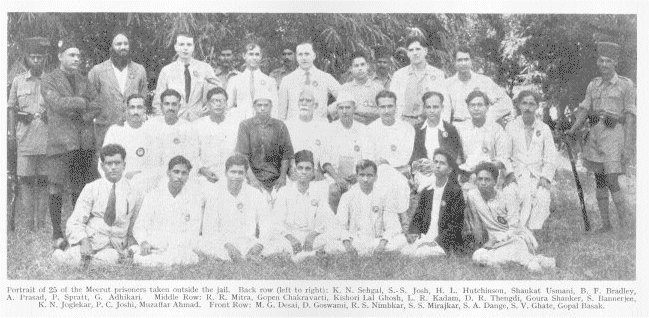

(Image above of Michael John Carritt and portrait of the 25 prisoners in the Meerut Conspiracy Case.)

The son of a distinguished lecturer from Oxford University, Carritt’s journey took him “from an ultra naive public schoolboy with a veneer of Oxbridge sophistication, classical scholarship and a mind full of conventional prejudices into a starry-eyed activist in the Indian Independence movement and in particular, its communist-led trade union and peasant committees,” as he writes in his book published in 1987— ‘A Mole in the Crown’.

Filled with personal “anecdotes and descriptions” of his “experience as a Government officer in India during the decade before World War II to review the process by which in the space of few years”, Carritt goes into some fascinating detail about how seeing the injustices of British rule first-hand turned him away from his own country’s colonial government to work actively for the resistance in Bengal led by the Indian communists.

Falling in love with the people

Growing up in England, neither his lineage nor privilege translated into academic excellence. After a modest stint at Oxford University, it was “service in the administration of India and Burma or the colonies [that] gave the best prospect of satisfying elitist requirements”.

In 1928, he joined the ICS and was posted to Bengal, which wasn’t a preference for new British ICS officers because of the region’s hot and humid climatic conditions, and burgeoning political violence at the time.

Despite these circumstances, Carritt recalls falling in love with the region and its people.

“I loved the Bengal countryside, whether it was the scorched, dusty, laterite upland of W Bengal… or the gentle evening light on the vast waterways of E Bengal. I came to love the Bengali people – nimble-witted and quick to laugh, but also easily moved to anger; warm in friendship but, more than most people, bitter in enmity,” he writes.

Carritt’s first posting was in Midnapore, which was considered Bengal’s “most troublesome and violently nationalistic district”, as Assistant Magistrate. His first encounter of the cruelty imposed by the British colonial government came in the form of a District and Session Judge whose “cruelty found its most unpleasant expression in an almost pathological contempt for Indians in general and a desire to make them suffer”. This came in the form of “notoriously severe” judicial sentences for the smallest legal infractions.

During his year-long stint there as a probationary officer, two District Officers (civil servants who performed the task of District Magistrate and Collector of Revenue) were assassinated, while the third “cautiously decided after two months of non-work” to resign.

By his account, none of the three District Officers were particularly impressive in service or held any regard for the people living in their jurisdiction.

After his stint in Midnapore, he was posted in Rangpur (in present-day Bangladesh), for training in ‘Land Settlement’, and it’s from here that he truly starts to witness and experience some of the horrific injustices of colonial rule.

As the retired IAS officer, T.C.A. Srinivasa Raghavan, writes in his review of Carritt’s book for The Book Review Literary Trust, “If the year under training exposed the pretensions, inadequacies and loneliness of the District Officers the author came into contact with the next few years, in the countryside as well as a short spell in Calcutta revealed the exploitation, hypocrisy and the snobbery behind the facade of the white man’s burden. The locations were as scattered as Rangpur in North Bengal on settlement training, Asansol in Burdwan district, the western frontier of Bengal, Tangail in Mymensingh District (now in Bangladesh) in the riverine Bengal plains, the last two as the sub-divisional officer and in Calcutta, as a special officer for a few months in charge of detention camp.”

Besides this, he also started to see how poor Bengali farmers were systematically exploited by unscrupulous moneylenders charging interest rates as high as 60 per cent on loans made during sowing time. As he travelled through Rangpur district making records of cultivators and the land revenue paid to the colonial government, he saw the hard toil of these poor farmers being regularly exploited by the local zamindars.

After his stint there, he took charge of Asansol subdivision in Burdwan district as “Chief Magistrate, Chief Executive Officer and Supervisor over the maintenance of Law and Order as well as Tax Collector”. One of his responsibilities in Asansol was to sit in court for 14 days a month and adjudicate on local disputes, even though he didn’t understand a word of Bengali. However, his growing sympathy for the downtrodden and exploited would often see him pass orders in favour of them over, say, a moneylender.

Of course, other British officers at the time noticed his growing partiality to Indians and soon he was transferred out of there to the Political Department in Calcutta (Kolkata).

The department’s task was to keep tabs on Indian Independence activists and control their activities. However, his seven-month stint there mostly revolved around basic paperwork and he was soon transferred to the East Bengal town of Tangail, where he witnessed the intense cruelty of the colonial government from the merciless beat down an entire village was given for the murder of an Englishman to the warped legal system which guaranteed harsh and often unfair sentences against political prisoners.

This is also the time when he started paying attention to Left-wing thinkers like Karl Marx, Lenin and others. He would use his official position to bypass the ban on communist literature and his brother would send these books.

Making matters worse was the Bengal governor, Sir John Anderson’s pronouncements praising the “law and order policies of Hitler”. This created a sharp “awareness of the shoddiness of the whole system and the gap between the professed benefits of civilised rule and the administration’s outspoken respect for Hitler and his new order which undermined” his desire to continue in service as before, notes Carritt. He left Tangail in the summer of 1934 and what followed from here was a long leave back home in England.

Harbouring ‘fugitives’

Here, he got in touch with the League Against Imperialism (LAI), an organisation headed by Ben Bradley, one of the convicts in the famous Meerut Conspiracy Case. It was the LAI that gave him contacts to the Communist Party of India’s Bombay branch. When he returned to India in 1936, he brought cash with him that would allow them to publish ‘illegal’ pamphlets. What followed for the next 30 months working out of the Writers Building in Calcutta in the ‘Political and Appointments’ division was remarkable.

As Raghavan writes in his review: “A courier to-start with, rebuffed out of timidity by [SS] Mirajkar (an Indian communist leader and freedom fighter out of Bombay), befriended by [Reverend] Michael Scott (a British clergyman and anti-apartheid activist) in his sullen way and happy to be rid of the contraband literature, which was freely available in Britain and a small sum of money from the Communist Party of Great Britain to Indian Communists. Contacts were however maintained and one comes across tantalizingly the names of the veteran Ajoy Ghosh, P.C. Joshi (General-Secretary of the Communist Party of India), Dange, Ghate and others. The author had to find shelter occasionally for the fugitives indefatigably keen on continuing with their mission. He participated as an onlooker and fraternal colleague in interminable discussions on the theory and practice of a united front against fascism. He could keep his tracks well covered, for on return from England he was appointed as undersecretary in the Political and Appointments Department, a vantage position indeed. But misgivings persisted that the fat may be in the fire and so, the author, as soon as he could, resigned and obtained his proportionate pension.”

Two years after resigning from the ICS in 1938, his £400 per annum pension was withdrawn on the grounds of “behaviour not compatible with approved service”.

The cancellation of his pension didn’t have too much of an impact because he went onto become a lecturer of philosophy at Oxford first and Sussex University.

It was only in 1980, after a researcher approached him, that he realised the British government had maintained a secret file on him. In the file, what was noted among other things, were suspicions that he was a Marxist with sympathies for the Indian freedom struggle.

Reportedly, the only reason why he wasn’t arrested was because of the public embarrassment the colonial government would suffer. He eventually passed away in 1990 at the age of 84 in Oxfordshire, but not before penning his memoirs where he writes, “given the same circumstances of time and history, I think I would choose the same sort of road.”

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

No comments:

Post a Comment