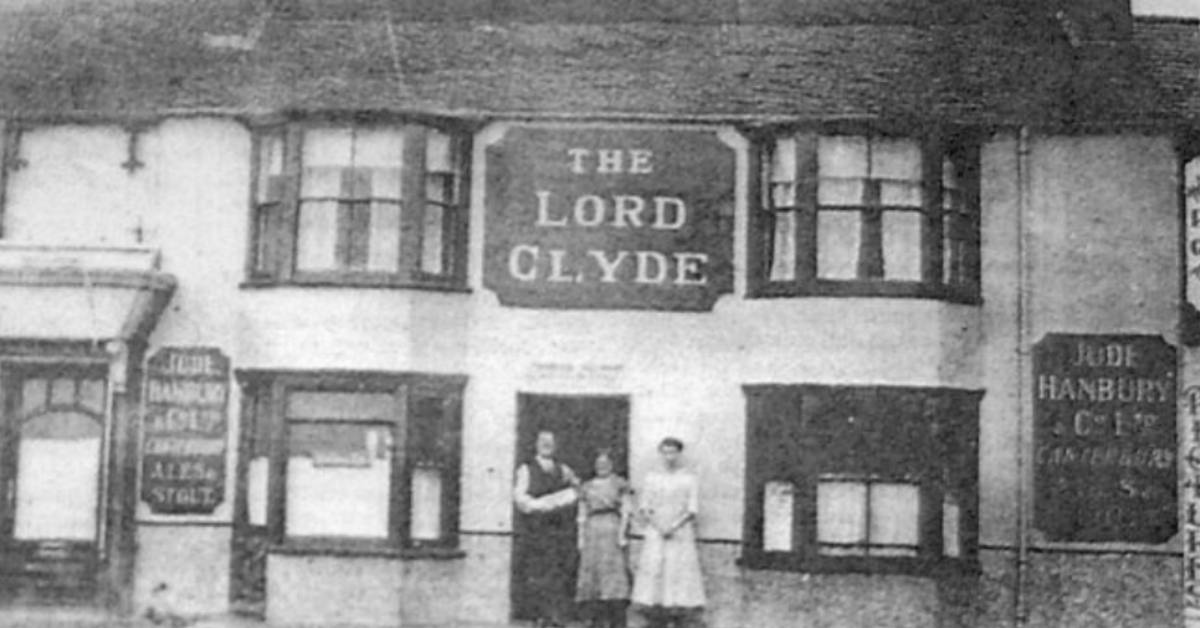

Dr Kim Ati Wagner, a Danish-British historian of colonial India, received a peculiar email sitting in his London office in 2014. It was from an old English couple who owned The Lord Clyde pub in Kent, a county in England.

They wrote that they had discovered a human skull hidden under a bundle of unused boxes and crates in 1963. The skull was missing its lower jaw, the few remaining teeth it had were loose, and a note was found lodged in its eye socket.

The note, written in elegant 19th-century handwriting, read:

“Skull of Havildar “Alum Bheg”, 46th Regt. Bengal N. Infantry who was blown away from a gun, amongst several others of his Regt. He was a principal leader in the mutiny of 1857 & of a most ruffianly disposition. He took possession (at the head of a small party) of the road leading to the fort, to which place all the Europeans were hurrying for safety. His party surprised and killed Dr Graham shooting him in his buggy by the side of his daughter. His next victim was the Rev. Mr Hunter, a missionary, who was flying with his wife and daughters in the same direction. He murdered Mr Hunter, and his wife and daughters after being brutally treated were butchered by the roadside. Alum Bheg was about 32 years of age; 5 feet 7 ½ inches high and by no means an ill looking native. The skull was brought home by Captain (AR) Costello (late Capt. 7th Drag. Guards), who was on duty when Alum Bheg was executed.”

In their email to Dr Wagner, the couple detailed how their years of internet searches on ‘Alum Bheg’ had come up short, and how they “did not feel comfortable with the ‘thing’ in their house, and yet did not know what to do with it”. Their research had, however, led them to Dr Wagner, who was known for his particular interest in the Indian Uprising. He wrote back, telling the couple that he would collect the skull to study it further.

“And so it was that I found myself standing at a small train station in Essex, on a wet November day, with a human skull in my bag,” writes Dr Wagner in his book, ‘The Skull of Alum Bheg’ (2017).

Dr Wagner also says that as he held the skull, and thought over how a man had “once looked through those eye-sockets” and “chewed with those teeth”, he was determined to “restore the humanity and dignity that had been denied to him”. And so he traces the life of Alum Bheg, a young soldier in the Indian Revolt of 1857, and how his remains ended up in an English pub over a century after his death, alongside highlighting the lesser-known chapter of this uprising in Sialkot, Punjab (now located in Pakistan).

Who was Alum Bheg?

For Dr Wagner, ensuring that this skull was, in fact, that of a late-19th century soldier was a difficult task, for no mention of Alum Bheg existed in the history that recorded the Revolt of 1857. Of the soldiers who had served in Sialkot, only three names existed in the records, and those were all of the soldiers who had stayed loyal to the British. Preliminary examinations of Alum’s name established that, firstly, the correct spelling of his name was possibly ‘Alim Beg’, and that he was a Sunni Muslim from North India. Dr Wagner details that Alum was a ‘havildar’ who was paid a sum of Rs 14 per month, which was double that of ordinary sepoys.

On 13 May 1857, a British trooper arrived at Sialkot to inform the regiment of the fall of Delhi and the violence in Meerut, which was increasingly getting out of hand. While deeply perturbed, the British establishment decided to maintain a facade of calm, possibly to keep their own soldiers in line. But Dr Wagner writes that the soldiers, as well as civilians of Sialkot, were well aware of the uprising taking place in other parts of northern India. Up until this moment, the soldiers would hide their discontent with the British and carry on with their duties, but “as news of the outbreak became known, the irritation of the sepoys increased”, writes Dr Wagner. “If the news of the mutinies at Meerut and Delhi burst upon [Sialkot’s] inhabitants ‘like a desolating cyclone’…the clouds had been gathering for some time.”

An innocent life caught in the wake of a war

Meanwhile, British occupants of the region had begun to feel a sense of fear with every passing day, hoping that their own infantry would not revolt the same way that Delhi and Meerut had. As July rolled in, an increasing number of whites had fled the area, but one Dr James Graham, superintendent surgeon in Sialkot, and his daughter had stayed back. The rebellion around the country had only reached Sialkot through letters and not in person.

However, the tone of the letters was becoming increasingly morbid and desolate, and so, on 9 July, Dr Graham and his daughter mounted a buggy and rode towards safety. However, Dr Graham was shot in the head. His daughter, Sarah, managed to escape to safety. Next to be killed were Reverend Hunter and his family, as detailed in the note.

However, it is pertinent to note that as Dr Wagner sat to trace Alum’s, as well as Sialkot’s role in the 1857 uprising, he found that, firstly, Dr Graham and the Hunters were killed on separate roads leading up to the Sialkot Fort. No evidence was found that Hunter’s wife and children—one of whom was a son, rather than a daughter, as incorrectly stated in the note—were “brutally treated”, i.e, sexually assaulted. Alum’s whereabouts on 9 July remained unknown, and he “might even have been one of the loyal [soldiers] who protected [British women],” Dr Wagner adds.

“What is clear….is that Alum was not responsible for the murders of Thomas and Jane Hunter and their baby, nor of that of Dr Graham; these were explicitly recorded as having been killed by sowars of the 9th BLC (Bengal Light Cavalry) or by Hurmat Khan, the ‘chaupprassi’. Several key eyewitnesses…were furthermore clear on this general point: the men of the 46th BNI did not kill anyone in Sialkot. Alum Bheg, in other words, was innocent,” Dr Wagner says.

Over the next four-five days, most of the Indian soldiers were captured. Some were flogged, some hanged, some shot, and some dismissed from service. Those who had remained loyal or saved the lives of Europeans were given promotions and financial compensations. Dr Wagner notes, “All Indian servants and soldiers who joined the uprising were considered simply as traitors and, regardless of their actual actions, considered equally guilty and deserving of the most severe punishment. The notion of betrayal was indeed central to the British understanding of the outbreak…”

Alum, considered the ringleader of the mutiny in the region, was sentenced to death. He was blown from a cannon. It was decided that his execution would take place in Sialkot to “set an example”, although what example was to be set was unclear – “There were no longer any sepoy regiments left to be forced to watch their comrades be blown apart, nor any crowds of sullen villagers made to witness the spectacle to the point of bayonet,” writes Dr Wagner. Alum was one of the very last rebels to be executed in this manner.

‘It’s time he came home’

Present at Alum’s execution was Captain Costello, and allegedly the person who decided to bring Alum’s skull to England with him, three months after he witnessed the execution. “What we will never know,” writes Dr Wagner, “is what moved Costello to pick up the bloodied head of Alum Bheg and go through the visceral process of defleshing the skull to bring the grisly trophy home…” However, this act was commonplace after the Uprising, wherein several British troopers collected the remains of dead soldiers as souvenirs. Details of how the skull went from Costello’s position to the Kent pub remain hazy. The owner of the pub, Lord Clyde, played a major role in suppressing the Revolt, and this could be a possible explanation for the final resting place of the skull.

The real murderer of the Hunters was eventually caught, but by then, Alum was long dead, and his skull had already made its way to some corner of Britain. Dr Wagner ends his book by making a poignant note of how Alum, “neither a martyr nor a murderer, deserves better than to have his remains displayed in a case or museum somewhere, or to be pressed into a political agenda he himself would not have recognised. Instead, it is high time he came home”, the author adds.

“It would be worth bearing in mind that the manner of Alum Bheg’s execution was deliberately intended to deny him his funeral rites, and, for what it is worth, I think the peaceful site of the Battle of Trimmu Ghat [where Alum and his fellow sepoys had taken refuge on the first day of the battle], on the island in River Ravi, which today marks the border between India and Pakistan, would be a fitting place to bury him. Ultimately, this is not for me to decide, but whatever happens in the final chapter of Alum Bheg’s story is yet to be written,” Dr Wagner concludes.

Edited by Yoshita Rao

No comments:

Post a Comment