In 1978, there was a devastating flash flood in the Indus valley of Ladakh, which claimed many lives and damaged many homes, particularly in Leh district. Seeking outside help, the then Member of Parliament (MP) from Ladakh, Diskit Angmo, who was popularly known among Ladakhis as ‘Ama Gylamo’ (Queen Mother) or the ‘Rani of Stok’, reached out to Sir Robert Ffolkes of Save The Children-United Kingdom, a non-profit.

Save The Children-UK agreed to send assistance and, for the next six months, organised relief work in coordination with the local administration. They saw a region long deprived of primary health facilities, accessibility to basic medicines for curable diseases, multiple cases of anaemia and stunted growth, and a high infant mortality rate.

Responding to these conditions, they initiated the Leh Nutrition Project (LNP) in 1979 and were allotted around 20 villages south of the Indus river by the district administration to organise relief work. In the four decades since, LNP grew into Ladakh’s first non-profit organisation (registered in 1988) and delivered yeoman service in child nutrition, education, rural development, livelihood generation, primary healthcare, watershed development, etc.

Celebrating LNP’s immense contribution to addressing the developmental needs of Ladakh’s remotest villages, a documentary titled ‘Mountain Changemaker: 40 Years of LNP Legacy’ directed by independent Ladakhi filmmaker Stanzin Dorjai Gya was released last month.

The documentary offers previously unheard insight into how Ladakh’s oldest non-profit addressed some of the region’s major rural developmental challenges.

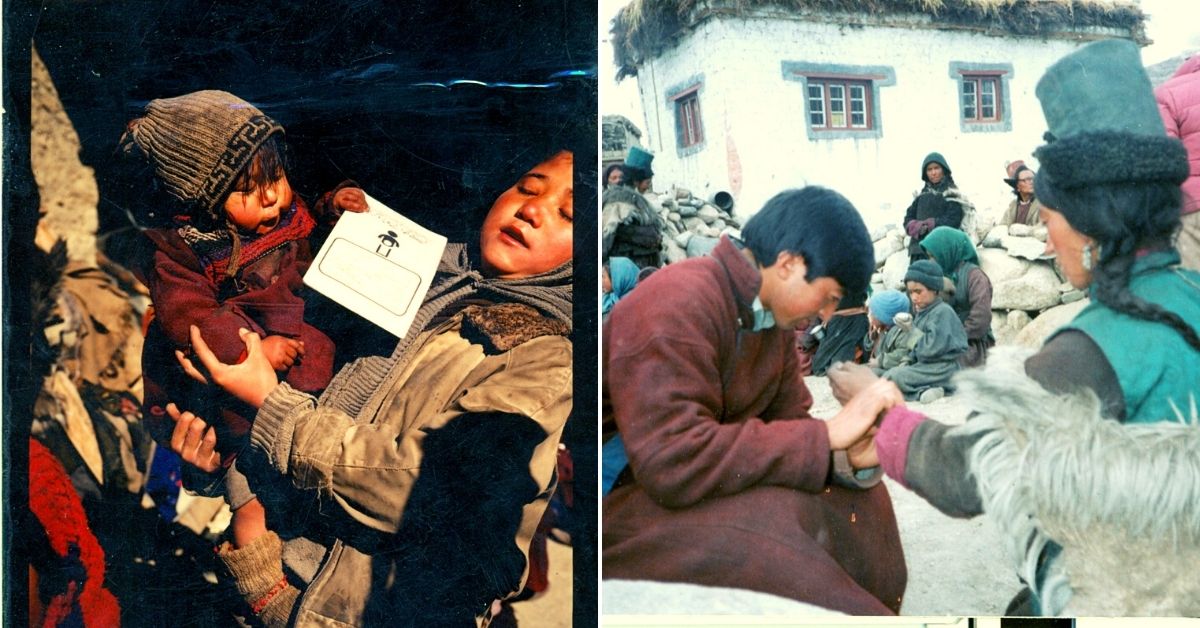

Thukpa Centres and Vaccines

“Our first objective was to work for the wellbeing of children. We first focussed on the south of the Indus river because foreigners weren’t allowed to enter the rest of Ladakh. Backed by a mutual understanding with the local district administration, LNP used to work in about 20 villages south of Indus from Singey Lalok to the Rupshu-Kharnak area in Leh district. Initially, our focus was on children’s health, education and well-being. We began by establishing feeding centres in these villages. In the early years, children from these villages suffered from anaemia, high infant mortality (180 per 1,000 births) and stunted growth. There was no serious fresh vegetable intake in their diet, which was dominated by meat. We initiated a supplementary nutrition programme, primary healthcare service, school education and building awareness. This was done in close cooperation with local authorities and sectoral agencies,” says Eshey Paljor, the executive director of LNP, speaking to The Better India.

The supplementary nutrition programme began in remote villages like Chilling Sumda, Skyu, Markha and villages near the Singe-La mountain pass, where children suffered from stunted growth. With an emphasis on nutrition, the initiative was called Leh Nutrition Project (LNP). These feeding centres were popularly known as ‘Thukpa Centres’ for serving Thukpa (nutritious porridge with a mix of rice, pulses, leafy vegetables and meat).

“Initially, LNP used to get ration and ‘Thukpa’ for the children made from rice, pulses, vegetables and spices. Villagers would go to Lamayuru village to fetch these items. LNP had appointed people from each hamlet who would prepare meals for the children. They would go and fetch the rations. No connectivity meant we would have to trek up to Lamayuru, and it was difficult. We used to get all this stuff by putting the loads on donkeys, and the trip would take two days. The first day, they would go and the next day come back with the items. Upon getting these items, they would prepare the meals and children from every hamlet were fed every day,” says Sonam Jordan Shaskarpa, a resident of Wanla village in Khalsi tehsil, in the recently released documentary ‘Mountain Changemaker: 40 Years of LNP Legacy’.

“Those feeding centres weren’t just for young children, but also pregnant and lactating mothers since at the time we didn’t have functioning Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS). Whenever our field staff or local health personnel visited, they would check the progress of each child. The feeding centres would provide supplementary nutrition daily with an emphasis on vitamins and minerals. Local volunteers who made the food would also measure arm circumference and other metrics. If these children were found anaemic, they were provided with a special diet and care. To assist us, we would have a government doctor, nurse on deputation and a medical assistant trained at Sonam Norboo Memorial (SNM) Hospital in Leh for two years who would end up joining LNP. Over three decades, our supplementary nutrition programme regularly impacted 41 villages and nearly 11,000 beneficiaries in the remotest corners of Ladakh, including Singey-Lalok, Lingshed, Wanla, Skyu-Markha, Gya-Miru and Kharnak,” recalls Eshey Paljor, who joined the LNP in 1983.

Underpinning efforts like these were an emphasis on training local human resources, imparting awareness, letting stakeholders take decisions and not imposing a top-down approach. This approach is what created an environment of sustainability in their efforts. For example, there was a Goba (Village Headman) and other important decision-makers who took key decisions regarding any LNP initiative at the village level. Instead of reinventing the wheel, what the people at LNP did was work with and strengthen existing institutions.

As Eshey notes, “About 35 years ago, vegetable cultivation in remote areas was barely practised. They had no experience of cultivating vegetables because of the climatic conditions. Instead of merely depending on sourcing vegetables from outside, LNP took some progressive farmers from around Leh to train residents of these remote villages. They taught locals things like making a garden bed, what should be its size, how much manure one should mix, what should be the depth of sowing the seeds and how much should be the gap between them. It was elaborately taught on the field.”

“We benefited a lot. Ajang (Uncle) Sonam came and taught us to cultivate cabbage and not cultivate just one vegetable. He said, ‘one should also grow cauliflowers, cabbages, carrots and anything else’. From that moment forward, we saw changes. Now everyone is growing cauliflowers, carrots and tomatoes. Those who have a greenhouse can grow eggplant, capsicum and almost everything. As a result of LNP’s efforts, we have benefited a lot. Now we can grow many crops and vegetables,” says Sonam Choron from Wanla.

Another area of focus in the first two decades was the delivery of medicine and immunisation.

“In coordination with the erstwhile Jammu and Kashmir state government and district administration, we also conducted immunisation drives for measles, DPT and polio, amongst others. We took the responsibility of inoculating about 6,480 children from 35 villages over the course of a 12-year period from 1983 to 1994/95,” claims Eshey.

And in those days when road connectivity was still a distant reality, the LNP team took foot journeys from winding paths in precarious mountain edges. On certain occasions, they would even trek about 15 days to immunise two to three children in a hamlet.

In the documentary, Chotak Gyatso, a Program Coordinator with LNP, talks about the difficulties in vaccinating children from these remote corners. “During those times, LNP oversaw efforts from Dipling to Rupsho-Kharnak. Immunisation was a challenging task during those days because first, the villages were far; second, it was difficult to maintain the cold chain of the vaccines. For example, if you go from Dipling to Lingdshed, it would take 25 days to get there by foot. One had to maintain the cold chain for that long,” he says.

With a deprived primary health system at the time, it was difficult to access medicines. Moreover, residents didn’t have the means of buying these medicines. Working with government doctors on deputation, LNP would often pay for the medicines distributed.

Ask Lundup Gyatso, the Sarpanch of Samad Rakchan village in Nyoma Tehsil.

“During those days, we did not have medicines for the children. Many children used to pass away due to lack of medication. So, LNP came and gave us medicines. Many children benefitted and as well as expecting mothers. They provided us with Thukpa and other nutritious food for children like milk and other supplementary. People in the Changthang area (eastern Ladakh) used to put fire on the hearth in the tent itself and cook, and the tea would be smoked. Whatever we cook would be infused with smoke. That is when LNP advised us of the ill effects of smoke on our throat and eyes. LNP gave all the villagers a Bokhari (cooking stove) free of cost to each household,” he says.

He also recalls how his village used to suffer from a water crisis. Residents would trek about 30 minutes with a can in hand to fetch water. In response, Lundup remembers how LNP set up pipes from the water source to ensure they had access to it on their doorstep.

“It has been almost 30 years since they’ve been visiting us. I have six children who are all beneficiaries of their work. During those days, there were a large number of infant mortality cases. After LNP came, all the children and expectant mothers got treatment. Some were even taken to Leh for treatment. Such was the help we got from LNP,” he recalls.

The emphasis on child rights, particularly in health and education, got a massive boost in parts of rural Ladakh thanks to the proliferation of IEC (Information, Education and Communication) material in the form of posters, leaflets and audio-visual mediums. On certain occasions, LNP workers would carry a television alongside a generator on their backs to remote villages and showcase films on child rights.

Educating and Empowering

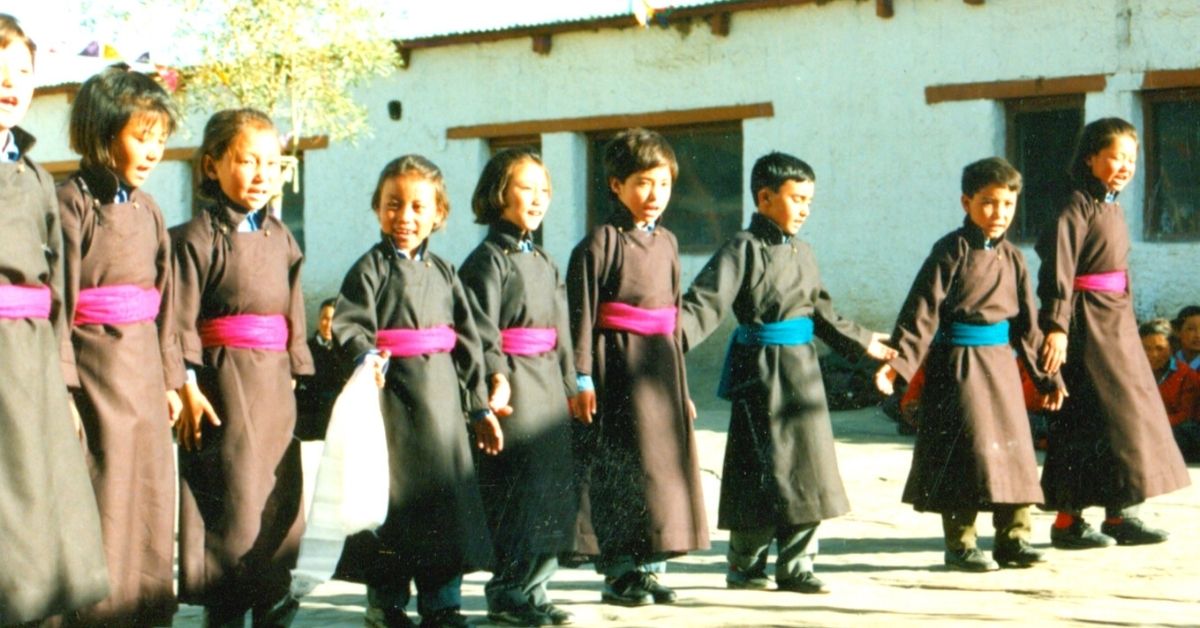

When it came to education, LNP knew it couldn’t do much about the school syllabus. What they could do was get teachers to these villages. The State education department had a system whereby if a village could build a school; they would have to appoint a teacher there. Since villagers couldn’t afford to build schools, LNP intervened.

“At that time, we did not have a school. LNP bought the land to construct the school. We can still see it standing right over there. They bought the land when villagers had no money. They gave books, uniforms, sports equipment and many other important things to children. This was around 30 years back. In winters, they even provided tuition fees for teachers. They even extended their program to Hinju, Ursi and upto Lingshed,” recalls Sonam Jordan.

According to Eshey, the LNP ran such schools in almost 16 villages.

Another key element in LNP’s educational initiatives is the child sponsorship program it ran to deter school dropouts and increase enrolments. Since its inception in the early 1990s, more than 500 students have been successfully sponsored. The initiative began as a collaboration between Save The Children, LNP and Lions Club, Leh.

In the documentary, Tashi Lanzom Cho, a nurse once deputed to Mangyu village, speaks of how LNP’s work inspired many young women not just to continue their studies but pursue a college education. Following a selection process, some women from villages like Yulchung-Neraks and Lingshed were sent by LNP to Leh for further studies. Many of them were able to finish college, while those who didn’t at least knew how to read and write.

“Deserving children who expressed a genuine desire to study but couldn’t afford an education were selected for the sponsorship programme. We provided little amounts of cash that they could use to buy stationery and books. Such sponsorship programmes were present in almost 17 villages. However, besides sponsoring children, LNP ran a similar initiative for families as well that would have about 12 to 13 members in one joint household and often just one male breadwinner,” explains Eshey.

Families could do what they chose to with the money. Tashi Phuntsog of Wanla Gyamtsa village, for example, constructed a house with two rooms with that sponsorship money.

Besides all these initiatives, LNP played a pivotal role in offering a multitude of livelihood opportunities. Take the example of Indus Tsestalulu Society, a women-led Self-Help Group (SHG) from Chuchot, Leh, which makes juices, jams and lollipops from locally-found fruits like sea buckthorn and apricot. It was founded with support from LNP about 30 years ago.

In the documentary, Yourol Palmo of Tsestalulu Society talks about how LNP trained them in the food processing business and even built a small manufacturing unit. She recalls in the early days using their own wooden spatulas and ladles to make pulp. With a capping machine, these women would make their own bottles and sell them. After picking up the requisite skills and setting up their unit, they began training other women-led organisations.

“Initially, only a few of us were there. Currently, there are 30 women in this society. After completing training, various NGOs across Ladakh asked us if we can impart training to other women associations. They took us to impart training to different places in Nubra, Shayok, Kargil, Sham and even Himachal Pradesh,” she recalls.

Climate Change and Looking Ahead

LNP was among the first organisations in India to recognise the effects of climate change on the ground in Ladakh with frequent droughts and water scarcity. These events began causing serious problems for farmers looking to sow their crops in spring. To address these concerns, LNP got Chhewang Norphel, a Padma Shri-award winning engineer, on board. He came up with the idea of building artificial glaciers, popularly known as Ice Stupas today.

After retirement from government service in 1994, Chhewang joined LNP’s Watershed Development Project and took over proceedings. Back when our parents were growing up, Ladakh would experience heavy snowfall throughout the winter. When spring broke in April and May, the watering of fields would happen with melted snow water. In certain parts, groundwater would be overcharged to such an extent that fields there were hard to plough.

Since the 1990s, however, the condition has changed rapidly. There was no water to drink. For farmers, the situation was even direr, with water unavailable for the sowing period. He constructed artificial glaciers in villages through the watershed project, particularly those located in valleys, which face water shortage during spring. This is a low cost and simple innovation, which he believes is eminently teachable. You can read our story to know more.

This is just one example of LNP changing with the times. With a new generation of social workers joining the cause, they are on the ground advocating more modern causes like greater participation of women in local governance. In terms of child rights, they recently conducted a ‘multi-sectoral assessment’ to understand what sort of interventions are required from an organisation that has long worked with Ladakh’s children.

Around 20 themes have been observed so far, including child sexual abuse, drug abuse, and other emerging issues. Other issues that they are addressing include organic farming and entrepreneurship development by leveraging traditional practices and community networks with modern innovations and technologies. In this regard, a major project they are looking to help realise is Ladakh Organic Mission 2025, which seeks to ensure that all farmers in Leh district practice organic farming. The new generation only has to look back at the incredible legacy LNP leaves behind to fulfil its mission.

(Edited by Vinayak Hegde)

No comments:

Post a Comment