As a child, Nuklu Phom loved spotting and naming birds of different species with his grandfather. However, by the time he became a teenager, these occurrences declined with the dwindling bird population. Now, as an adult, Phom is trying to restore the ecology to its former glory.

Phom is an environmentalist from Nagaland’s Longleng district, who has dedicated most of his adulthood to increasing the population of the Amur falcon, planting thousands of trees, preventing poaching, and executing the concept of community-owned forests.

Phom, who lives in Yaongyimchen village, recently received the Whitley Awards 2021 by UK-based Whitley Fund for Nature (WFN). Also known as the ‘Green Oscar’, the award gives each winner £40,000 to scale their existing projects. Phom, now in his forties, will utilise the funds for the ‘Biodiversity Peace Corridor’ (BPC) initiative.

“The BPC will involve close to 50 villages across Nagaland that will refrain from indiscriminate exploitation of forest produce by engaging in alternate livelihoods. This will resolve conflicts between man and animals, as well as fights that erupt between communities for land and water use. We are already seeing the positive impacts of BPC in three villages. The recognition will hopefully speed up the implementation in other areas,” Phom tells The Better India.

According to him and his organisation, Lemsachenlok, close to 1,000 hectares of fertile land have been dedicated to plantation activities and roosting falcons. Since the project’s inception in 2007, the population of falcons has increased dramatically — from 50,000 to a million, Phom says.

Nagaland Chief Minister Neiphiu Rio recently congratulated Phom on Twitter for winning the prestigious award for grassroots conservation.

Congratulations to Nuklu Phom the only person from India to win the prestigious #WhitleyAwards 2021 for his work; “Establishing a biodiversity peace corridor’.

The award is one of the world’s leading prizes for grassroots conservation. My best wishes for all his future endeavours pic.twitter.com/ypfE6PyIwb— Neiphiu Rio (@Neiphiu_Rio) May 13, 2021

A passion project

Born and raised close to forests and wildlife in the eastern part of Nagaland, Phom has always known coexistence with nature. While his ancestors were dependent on the forest for survival, they were mindful of their extraction activities. They knew what must be preserved to avoid a catastrophic drop in wildlife and ecology, he says.

Phom grew up listening to his grandfather’s concern for future generations, “It was only after his death that I realised that what he said was true. Around 2010, I returned to the village after my studies and joined the Yaongyimchen Community Biodiversity Conserved Area, a village group that spreads awareness about the cause. I took up a teaching job and worked with the group for seven years. However, we needed to move beyond just awareness to on-ground execution, and that’s when I established my own organisation, Lemsachenlok,” he says.

Lemsachenlok, launched in 2017, comprises the elderly, students, women and scientists.

Phom had several issues to solve, such as drying water bodies, abandoned wells, hunters, poachers, chemical farming and more.

Dr Lima, a member of the organisation, says,“In Nagaland, land ownership of forest or river either belongs to an individual or a clan, so asking communities to set aside land for conservation was the biggest challenge. They made money from selling timber, wood, forest produce and animals. Another alarming issue was an invasion of cash crops and the depletion of indigenous ones. Rampant use of chemicals degraded land fertility. We had to address all these problems simultaneously as if even one issue persists, the project cannot work.”

The first step was to convince families to keep aside some part of their forest land and implement a trespasser’s rule. Once they got the land, the organisation started replanting trees for birds and animals.

The team also approached farming communities to reduce the traditional practice of ‘slash and burn’ for jhum cultivation. This is the process of burning the land to clear leftover vegetation in order to grow new crops. They helped farmers replace cash crops with indigenous plants including jackfruit, mangoes and nitrogen fixation trees. Some patches of trees are reserved for birds such as falcons and hornbills.

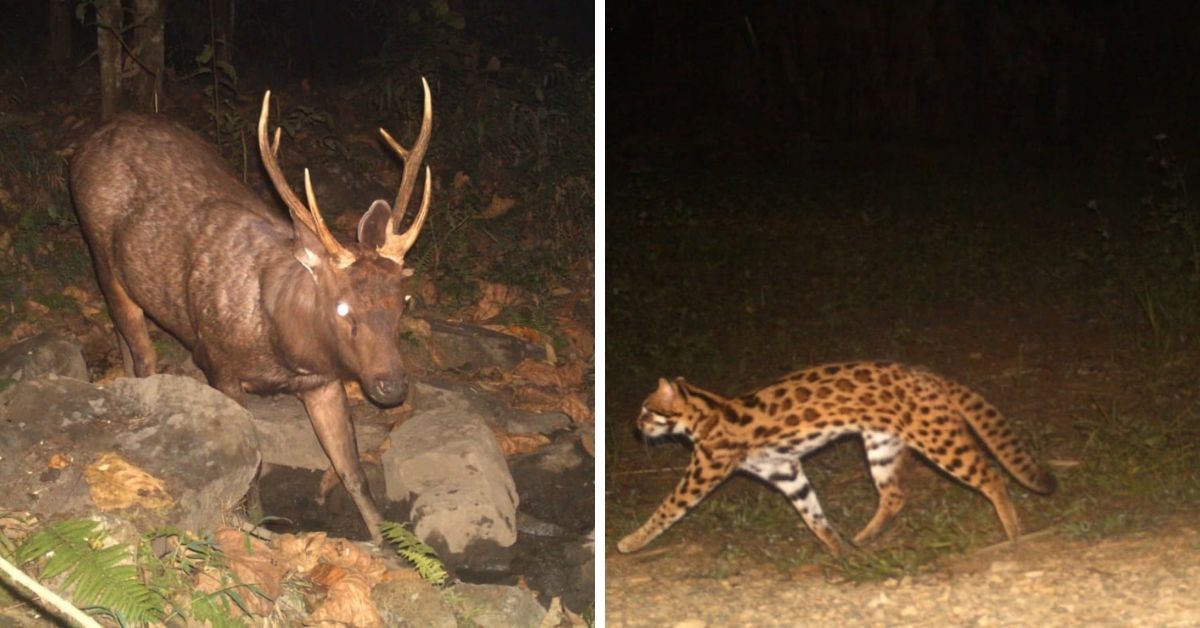

“We started with 500 hectares, which has now increased to 1,200. The falcon population has also increased tremendously. We are now able to spot 400-500 hornbills at a time, while they were earlier endangered. Other wild animals such as owls, barking deer, green emerald and mongoose can also be spotted in the protected areas. With proper intervention, we have been able to reduce falcon shootings. Every migration season, the falcon would be sold for Rs 80 or more in the local market. We informed locals about the benefits of falcons – such as how they feed on insects that destroy crops. We also told them that farmers in southern Africa start their cropping season only after the arrival of falcons. It worked,” says Phom.

For its efforts, Lemsachenlok was recognised by the United Nations Environment Programme in 2015 and bagged the India Biodiversity Award in 2018 and a Governor’s Gold Medal Award in 2021.

The team is now helping people switch from hunting to alternate professions such as crop cultivation and fishing, and is also introducing ecotourism activities for generating income. They are also building water reservoirs to save rainwater and increase groundwater tables.

“The motive behind all these efforts is to coexist with animals and nature. My grandfather was never preachy about this, for his actions spoke louder than words. I hope to imbibe that value and continue conservation efforts for as long as I can,” adds Phom.

Featured image source: Whitley Awards

Edited by Divya Sethu

No comments:

Post a Comment