Nekram Sharma was in his teens when he witnessed the implementation of the government’s policy on fertilisers in the Karsog valley of Himachal Pradesh’s Mandi district. In the 1980s, the promotion of fertilisers and monoculture (or single crop) farming through subsidies led to farmers, including Nekram’s father, switching to increased use of fertilisers and shift from millet crops to cash crops for higher profits.

By the time Nekram took over his family’s farmlands in the mid-nineties, the soil and land fertility were in doldrums. His land was addicted to harmful chemicals. Switching to organic farming overnight was not possible, so every year he reduced the volume of fertiliser. In 2005, he got rid of fertilisers altogether.

However, there was another task at hand — to bring back millet cultivation, not only to save his land from degradation, but also offer healthy food to consumers. Nekram was not chasing profits, so taking a risk suited him.

He travelled to various districts to acquire knowledge on ancient farming techniques from elderly farmers, some older than 100 years.

A majority of them shared an indigenous practice called Nau-Anaj (nau is 9 and anaj is crop). It is an intercropping or mixed farming method to grow nine foodgrains on the same piece of land. These crops are a combination of lentils, cereals, vegetables, legumes and creepers.

“The idea is simple — to have backup harvested crops in case one of them fails due to climatic conditions or pest attacks. This ensures that even if the farmer cannot sell the crops for some reason, he still has food for his family. What makes this technique interesting is that unlike traditional practices, where crops constantly fight for sunlight and water nutrients, the nine carefully assorted crops aid each other’s growth instead,” Nekram, now 58, tells The Better India.

In 2010, Nekram implemented Nau-Anaj and witnessed staggering results, which inspired other farmers in the region to follow suit. It also led to the formation of Parvatiye Tikau Kheti Abhiyan (PTKA), a co-operative of farmers.

“Once I was confident of the method’s success, I started teaching others and sharing my experiences. Today close to 5,000 farmers in the district have adopted this practice. My wife, Ramkali, has been running a seed bank through which we preserve desi seeds and distribute them to encourage others,” adds Nekram.

Shyam Singh from Bakhrot village, who served as a Zilla Parishad member for ten years, says the response to Nekram’s farming technique has been tremendous, and close to a hundred farmers in his region have adopted this method.

“Nekram is very articulate about the farming process and I am glad millet-based cropping has returned. The 9-crop system has multiple benefits to this system including raised fertility, less water and zero inputs costs,” says Shyam.

Nau-Anaj: How it works

The aim is to choose crops that use less water, fix nitrogen, increase soil fertility, repel insects and grow faster in small lands. It took Nekram nearly 5-6 years to attain that perfect combination as per weather conditions and water availability in the region.

“I made notes on properties of every crop during my research period and experiments, but I had to modify the data over and over again. I learnt that foxtail millet, which is rich in Vitamin B12, assures yield in drought and floods. Additionally, millets are rainfed crops so their roots will absorb all the excess water and prevent floods. Meanwhile, mustard is a nitrogen fixation crop that can be planted next to wheat, which extracts nitrogen from the ground. Likewise, dal and flax seeds are companion plants,” says Nekram.

Plant diversity enhances soil fertility and provides varying fodder options for farm animals. There is no fixed combination template as long as the farmer ensures there is diversity. This system will also keep pests and diseases at bay, he adds.

Nekram cultivates nine crops throughout the year on his five bhiga (less than an acre) land which include maize, moong, beans, rajma, urad dal, ram dana (Amaranthus), foxtail millet, finger millet and buckwheat. On the sides, he plants fruit-bearing trees such as mango, pomegranate and lichi, which act as natural fencing.

“Dals are planted under every tree as they are best known for their ability to fix nitrogen. I have also planted turmeric, which is an insect repellent crop, under one tree. In between onion plantations, I planted foxtail millet. I discovered this combination accidentally. It’s an example of how to grow more plants in less space. We have planted coriander, an insect-repellant, in different spots to eliminate the need for fertilisers,” says Nekram.

‘Why I have zero input costs’

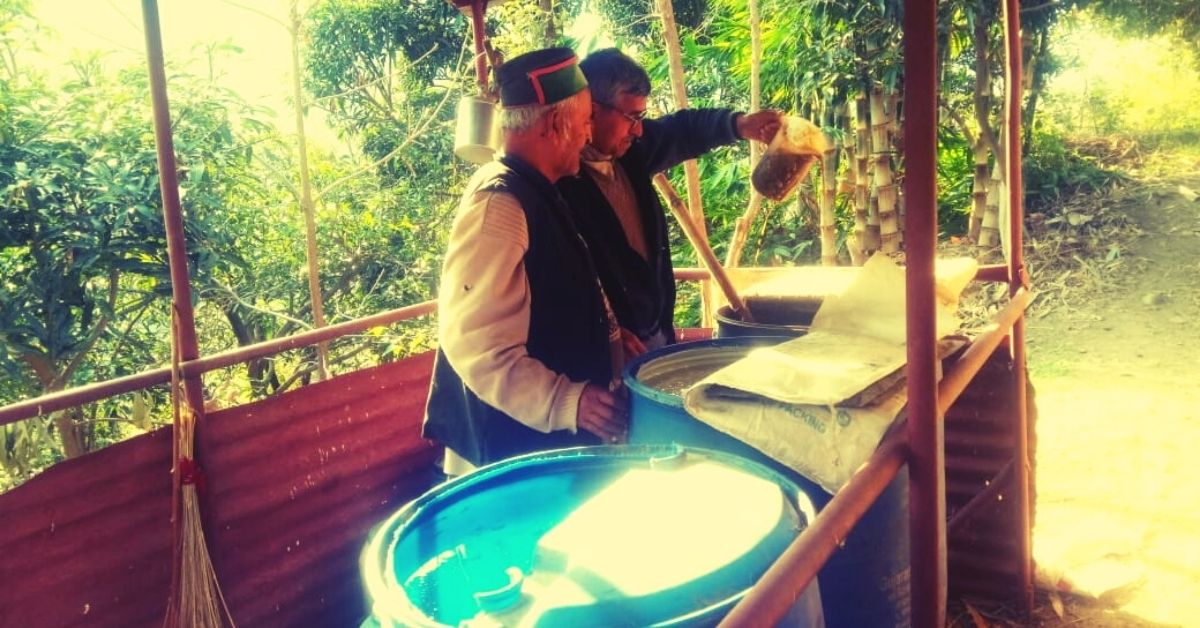

Fertilisers form the major part of agricultural input costs, followed by compost, seeds and water. In 2005, when Nekram shifted to natural farming, he started using a mixture of cow dung and cow urine (jeevamruth) to make plants healthy and kill the pests. He also acquired information on home-made alternatives to chemical fertilisers

Ramkali, who helps her husband on the field, says, “I make a spray of garlic, neem or lassi to prevent plant diseases. We make jeevamruth from our cow, thus eliminating any expenditures. These hacks may not work for everyone every time. If you pay close attention to your plants, you can identify the right solutions. For example, compost is most effective after sunset.”

The Sharma family’s seed bank further saves money on purchasing new seeds. By not using chemicals, the overall water usage has come down by 50%, says Nekram.

“Hybrid seeds need more chemicals that absorb a lot of heat. To keep the plants cool, a farmer has to use extra water. This isn’t the case for desi seeds. Additionally, when crops are planted close to each other they use less water. Some crops also act as natural mulchers or provide shade keeping the ground cool, thus requiring less water,” says Nekram.

Similar to Nekram’s farming, there is another technique called Baranaj (12 crops) pioneered by Vijay Jardhari in Uttarakhand. He is also the founder of Beej Bachao Andolan, and has inspired hundreds of farmers to implement the indigenous cropping method. Read his story here.

Edited by Divya Sethu

No comments:

Post a Comment