When Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister, passed away on 27 March 1964, his friend and confidant, the 19th Kushok Bakula Rinpoche—a Buddhist spiritual leader and MLA representing Leh at the time—was in deep mourning.

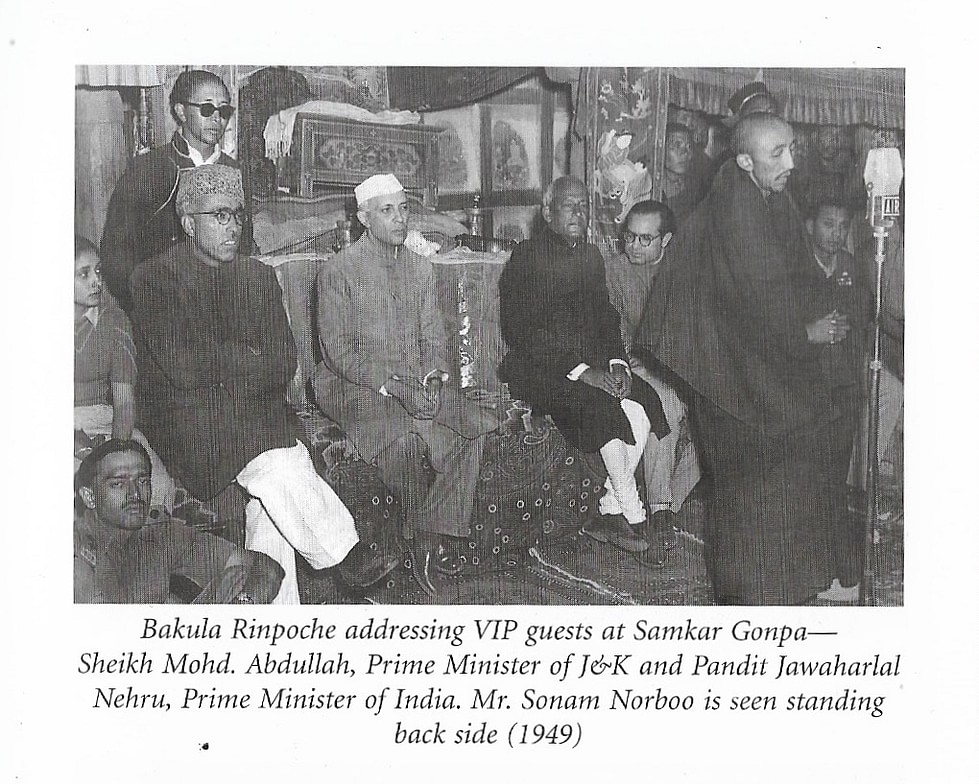

(Image above on the left of Kushok Bakula Rinpoche greeting Prime Minister Nehru in Leh on 4 July 1949.)

After all, it was Nehru who convinced Rinpoche to enter politics in service of the Ladakhi people. Following Nehru’s advice, Rinpoche would go onto serve in a multiplicity of roles as a minister in the erstwhile Jammu and Kashmir government, Member of Parliament and its tallest political leader of the 20th century with distinction. Decades later, he would also serve India as Ambassador to Mongolia with distinction. Such was his contribution to the people that former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh once called him the ‘Architect of Modern Ladakh’.

Offering his deepest condolences to Nehru’s daughter and future Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi, in a letter dated 1 June 1964, Rinpoche wrote:

The passing away of our most beloved and distinguished Pandit ji is one of the saddest events in the history of man. Mother Earth has become poorer. Man will have to perform deeds of merit for thousands of years before [another] one like him walks upon this earth again…It is the pious wish of our people that a portion of the last remains of the ones who took so much interest in their well-being should be taken to Ladakh so that they may have the sacred opportunity of showing their reverence according to their religious rites. This implies the building of a Stupa and enshrining the sacred remains therein. I would therefore, request you kindly to feel considerate to our deeper sentiments and oblige us by giving a portion of the last rites of our Pandit ji in favour of the people of Ladakh.

Like millions of their fellow Indians, people in Ladakh held Nehru in high esteem. This is the story of how the first Prime Minister’s visit to Leh changed the history of Ladakh.

Identifying Potential

Incursions by the Pakistani tribal raiders in 1947-48 had brought into sharp focus the vital importance Ladakh held as a strategic border area. In early 1948, when tribal raiders from Pakistan had made incursions into Ladakh, Rinpoche had successfully coordinated Indian efforts on the ground to protect the region. A year later, when discussions were ongoing in the United Nations for a plebiscite in Jammu and Kashmir, Rinpoche received an invitation to meet Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in person on 20 May 1949 at his residence in Teen Murti Bhavan, New Delhi.

Thus, in the spring of 1949, accompanied by a delegation and Mr Wangbo Nangso as the interpreter—since Rinpoche at the time couldn’t speak Hindi, Urdu or English—he set off on a long journey to New Delhi. They reached Srinagar on foot and horseback, and from there travelled to Delhi by road and rail.

For Rinpoche, there was a lot at stake here. The fate of Kashmir, and consequently Ladakh, was still hanging in the balance with the United Nations calling for a plebiscite to determine its future.

At such a pivotal moment in history, there were naturally some nerves. But upon meeting Nehru, all those nerves dissipated. His warm and affectionate nature had put Rinpoche at ease. During the meeting, he reiterated the position taken by an earlier delegation of the Ladakh Buddhist Association (LBA) about why the cold desert should remain with India, irrespective of the plebiscite’s outcome. This point had to be spelt out explicitly to the Indian leadership, to clearly distinguish Ladakh in their minds from the neighbouring but very different region of Kashmir.

Besides making these points, Rinpoche also mustered up the courage to invite Nehru to Ladakh. To his surprise, Nehru accepted the invitation and promised to visit Leh at the earliest possible date.

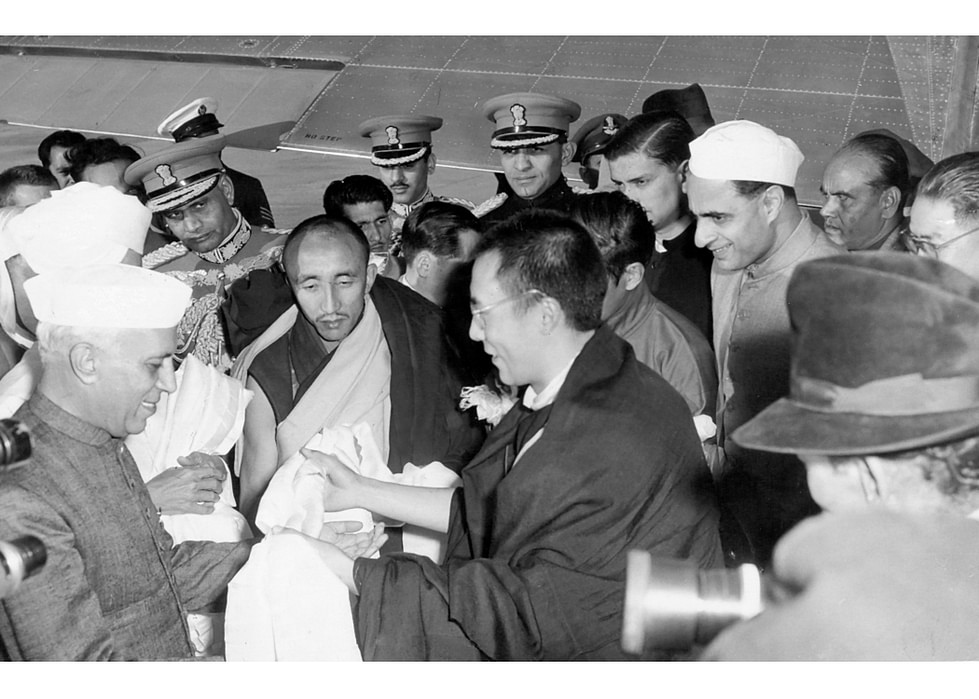

True to his word, Nehru landed in Leh barely two months later on 4 July 1949 on the same makeshift airstrip near Pethub Monastery which had been first prepared during the Pakistani incursion. This was the first time India’s top political leadership had visited Ladakh. Accompanying Nehru were his daughter Indira, Sheikh Abdullah, Defence Minister Krishna Menon, photojournalist PN Sharma and BBC India correspondent Sati Sahni.

After disembarking the plane, Nehru was greeted by a delegation led by Rinpoche. The delegation from New Delhi was provided with horses to ride up to the old provincial officer’s bungalow called Wazir Bangla, where they would reside during their visit.

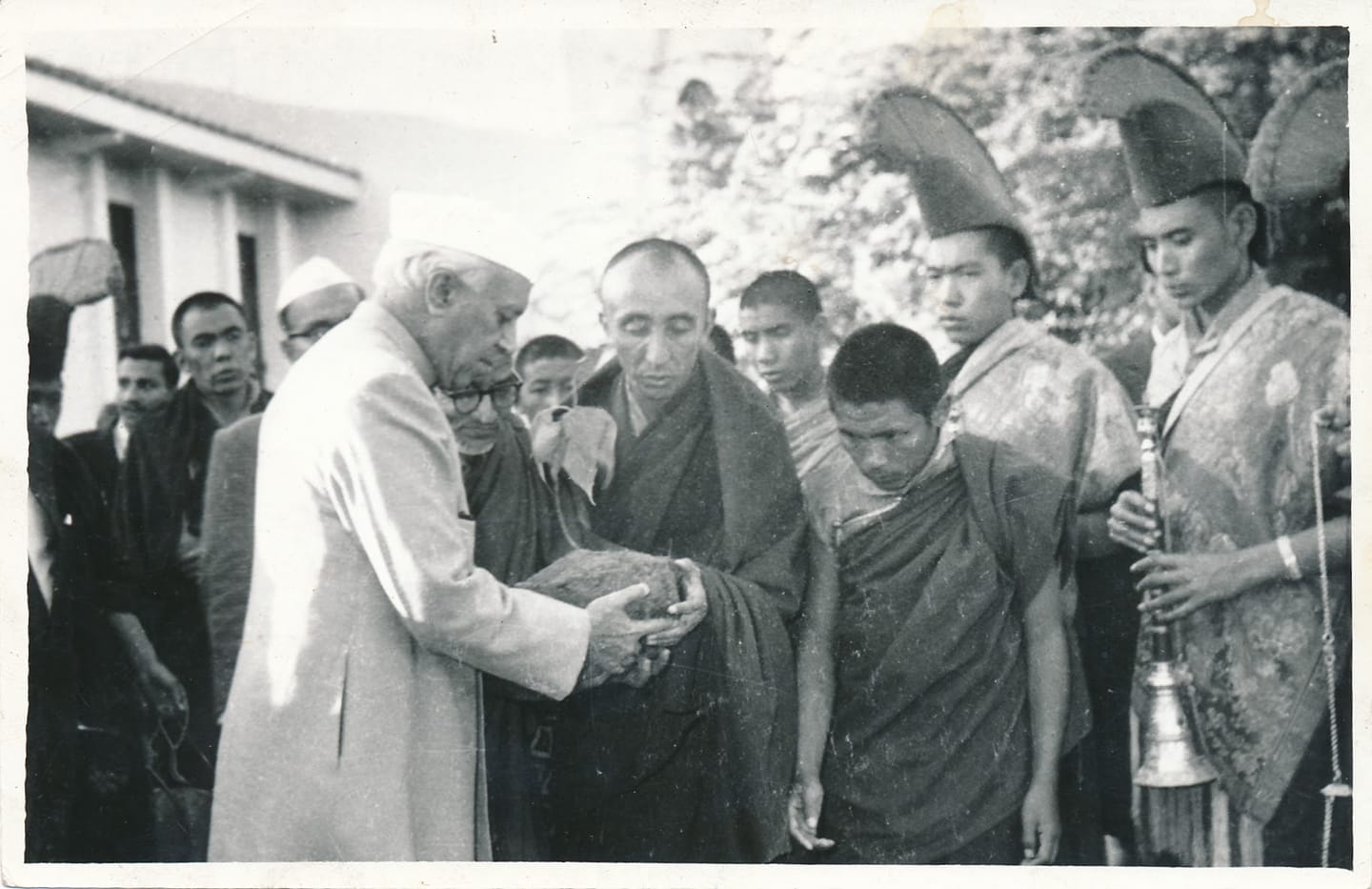

The primary objective of this four-day visit was to assess first-hand the needs and challenges of this unique region. During his stay, Nehru met with many local delegations and patiently listened to their concerns, demands and aspirations.

It was during a reception along the banks of the azure-blue Indus River when notable representatives of the Buddhist and Muslim community unanimously chose Rinpoche as their representative to both Nehru and Sheikh Abdullah.

At a subsequent meeting at Wazir Bangla, Nehru patiently explained to Rinpoche the new system of democratic governance being established in India.

“Then, with an implicit recognition of Rinpoche’s spiritual priorities and education, he made him a fateful offer. The Prime Minister said that Rinpoche should consider combining his spiritual leadership with political leadership, for the sake of the people…And no one was better placed or better suited to discharge this duty of leadership, he said, than Rinpoche himself,” writes Sonam Wangchuk, who served as his personal assistant for three decades, in his book — ‘Kushok Bakula Rinpoche: The Architect of Modern Ladakh’.

Naturally, Rinpoche was taken aback by the offer from the Prime Minister. After gathering his wits, he initially declined the offer. The rationale he put forward to Nehru was that his vows as a Buddhist monk made it difficult to participate in worldly affairs. Moreover, he knew little about the rest of India, modern politics and didn’t understand English or Hindi.

However, Nehru had closely observed his leadership qualities and how he was held in high esteem both by the Buddhist and the Muslim population. Nehru was convinced that Rinpoche was the man to lead Ladakh into the future, and made further attempts to convince him.

“Pandit ji reminded him, kindly but firmly, of Buddha’s teaching to work for the well-being of others…there could be no better opportunity than this [entering politics] to help free the people of Ladakh from the shackles of poverty, ignorance and deprivation,” writes Sonam.

Meanwhile, Nehru and Sheikh Abdullah also promised to issue their total support, if Rinpoche decided to change his mind and take up the offer of entering politics.

Even then, Rinpoche was filled with apprehension and doubts. He needed some time to think it over and would inform Nehru of his decision before he left for New Delhi. Meanwhile, word got around in Leh of this offer and soon a steady stream of elders (both from the Buddhist and Muslim community) came to Samkar Monastery in Leh, where Rinpoche was residing, to convince him and offer their support.

After much contemplation, Rinpoche realised that his own Bodhisattva vows committed him to do whatever it took to alleviate the suffering of others. And he remembered how Nehru said that politics offered a massive opportunity to put that commitment into practice.

He accepted his role as Ladakh’s political representative only on the condition that it doesn’t interfere with his commitment to Buddhist ethics and the routines of monastic discipline. He was not going to compromise on these two facets and conveyed the same to Nehru.

The Prime Minister’s last day in Leh was a public address where he announced the formation of a team of experts from New Delhi, who would assess the requirements of the region. He also promised to assist Ladakh’s developmental goals and facilitate the region’s integration with India.

“Nehru’s short visit had an abiding impact on the people of Ladakh. It gave them a sense of security and belonging concerning the new democratic, secular and socialist independent India. In Pandit Nehru, they saw a visionary, but also a man with a simple and sincere heart, who genuinely cared about the welfare of the people,” writes Sonam.

Till Nehru’s demise, both worked very closely with each other to fulfil the goals of Ladakh’s developmental integration with mainland India. Nehru helped him significantly in discharging his duties as an elected representative of the Ladakhi people. The two men developed a close personal bond which continued till the last days of Nehru’s life.

“Rinpoche was struck by Nehru’s personal faith in Buddhism and his genuine dedication to the cause of uplifting the plight of the poor and downtrodden in India,” adds Sonam.

Yet, there were some major setbacks along the way. In his book ‘India after Gandhi’, historian Ramachandra Guha refers to how Rinpoche had warned the Government of India in 1955 of the severe danger facing Tibet and its potential fallout on India, as reports came in of growing Chinese presence in the region.

As the story goes, Rinpoche led a delegation deputed by the Nehru administration to coordinate with the then-Government of Tibet, based in Lhasa, for the participation of the Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama in the 2500th Buddha Jayanti celebrations, scheduled to take place the following year across India.

On his return to New Delhi, Rinpoche warned Nehru of the situation in Tibet. Unfortunately, his warnings were ignored, and the consequences of their inaction are well-documented, particularly the capture of Aksai Chin by the Chinese.

Despite the horrors of the Chinese aggression in 1961-62, Rinpoche never rubbed the debacle in Nehru’s face, and worked tirelessly for the resettlement of Tibetan refugees following their influx. Already under the weight of immense public criticism, Rinpoche had too much respect for him to pile on.

After all, without Nehru’s explicit intervention, Rinpoche would have never entered politics in the first place. And without Rinpoche, who knows what trajectory Ladakh would have taken.

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

No comments:

Post a Comment