The year was 1903, and the otherwise quiet village of Great Wyrley in Staffordshire county, England, was bogged down by a terrifying occurrence. A series of gruesome slashings of horses, cows and sheeps had the area’s residents worried sick. Horrified villagers would wake up every day to find their cattle lying mutilated across fields, and the area soon began to be known as the “village of fear”.

The M.O was always the same. The killer came in the middle of the night, slashed the animals, and then disappeared without a trace. The local police tried to crack down, increase surveillance and nab the culprit, but to no avail. Children were told not to venture out at night, and people began locking their cattle up.

Things became worse when the police began receiving letters from a supposed gang, which named their alleged members. One name, in particular, stood out.

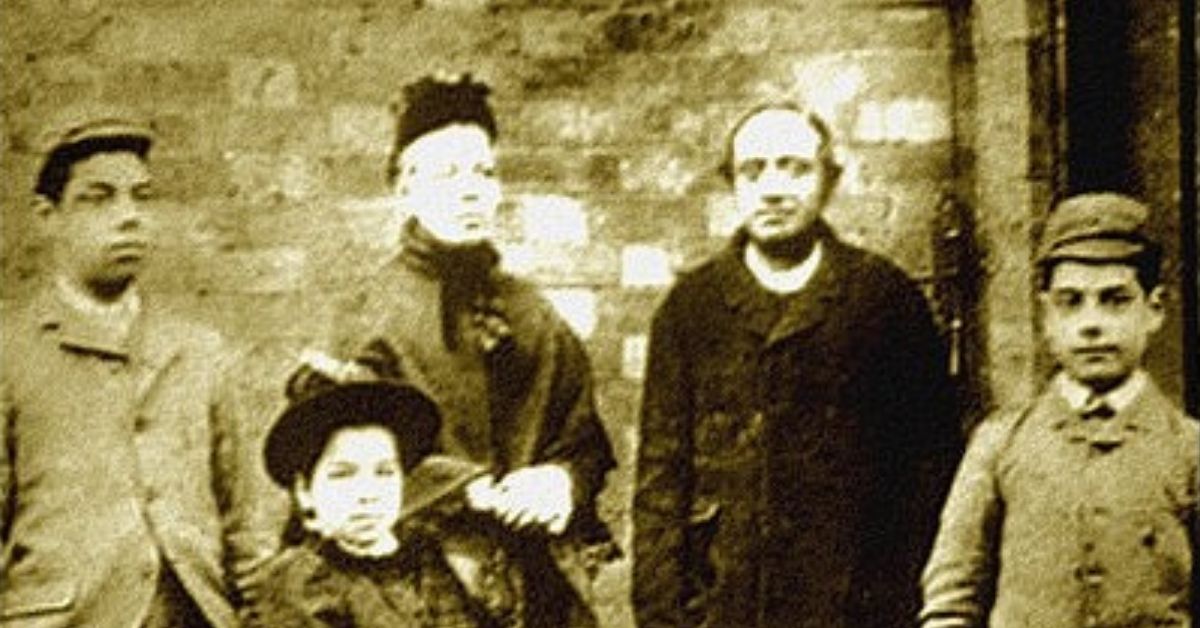

It was that of one George Edalji, a half Parsi, half English man who was a village resident. He was the son of Reverend Shapurji Edalji, a Bombay-born man who had travelled to England and eventually became the first person from South Asia to be made a vicar of an English parish.

To understand why George was a particular person of interest in this notorious case of cattle mutilation, we must first understand his life as a person of colour in an otherwise white society.

Who was George Edalji?

George was the eldest of three children to his parents, Reverend Shapurji and his English wife, Charlotte, born in Great Wyrley in 1876. The area in which the family lived was apprehensive about non-whites in the village, and George had always been subject to hostility and racism. Today, a better nomenclature for this phenomenon exists — ‘institutionalised racism’.

Much before George was accused of the heinous animal killings, the Edaljis had been subject to harassment and threats. In his book ‘Conan Doyle and the Parson’s Son’, Gordon Weaver details how Captain Anson, posted as the Chief Constable of Staffordshire, held the then-common view that those of foreign origins were miscreants or villainous. He questioned how “this Hindoo, who could only talk in a foreign accent, came to be the clergyman of the Church of England and in charge of an important working class Parish”.

Much of the misfortune that befell the small English village was pinned on George. These included anonymous letters to a member of the parish council detailing the sexual abuse of his 10-year-old daughter and naming George as the sender, as well as anonymous threats being sent to various village families.

Meanwhile, as a student, George was actually a quiet and studious boy who had won accolades for his academic performance and even written a book about railway laws. It’s said that he led a generally mundane life — taking the train to work every evening, returning home, eating dinner, and falling asleep. He was never seen drinking at the local watering hole and more or less kept to himself.

Real-life Sherlock Holmes

In 1903, George was 27 years old and working as a solicitor. Around this time, maimed cattle began showing up all over Great Wyrley, starting with two horses on February 1 that year. While livestock killings were commonplace in settling scores in the farming communities, the village had never seen murders of such levels, and there was widespread panic.

Owing to the suspicious nature with which George and his family had always been viewed by the police force and residents of Great Wyrley, the law forces began observing the young lawyer. Captain Anson, in particular, heavily suspected him. Years later, he alleged that Edalji had had a reputation for roaming the area late at night, and on a few occasions, footprints at the scene of the crime led to the vicarage and its surrounding areas.

On August 18, an injured pony was discovered early in the morning. A police team arrived at George’s house and recovered a coat, a few razors, and a pair of boots. They claimed the coat had hair that resembled the pony’s and that the razors had been used as a weapon of some sort. George’s affirmations that he had not left his home that night fell on deaf ears. He used to share his room with his father, the Reverend, a fact that the police found absurd because George was nearly 30. And so, even as Reverend Shapurji claimed that George had been in the room the entire night, the police arrested the solicitor.

In prison, George spent his time reading books about an English private detective, who cracked the toughest cases with his exceptional skills of deduction, observation, reasoning and forensic science. Meanwhile, his own case had gained the attention of top lawyers across the country, and the public quickly rallied with him, with a petition to have him released, gaining over 10,000 signatures. George was released on parole after three years, but the stench of the crime clung to the air around him, and he was barred from continuing to practice as a solicitor.

Desperate to clear his name, George wrote to the author of the book about this famous detective, none other than Sherlock Holmes. Around four hours away, in Edinburgh, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was recovering from having recently lost his beloved wife, Louise. When he received George’s letters, he knew helping out a family burdened by the grief of their oldest son being falsely accused would be the best way to pull him out of his own misery.

Before this, Doyle had often received requests and letters from readers everywhere to don the hat of his most famous creation and help them solve crimes. But never before had he paid heed to any of these. Something about George’s appeal, however, stood out. And so he wrote back to the Parsi, setting up a meeting in London’s Grand Hotel on Charing Cross.

George arrived at the hotel on the decided date, a few hours before Doyle. As he sat waiting, he was biding his time reading newspapers placed in the lobby. When Doyle arrived, right off the bat, he noticed the young lawyer bending close to read the newspaper properly. Almost immediately, it dawned on the author — George’s eyesight was compromised, a fact that had never been brought up in all those years of the trial.

The murder accused confirmed to Doyle that he was, in fact, astigmatic. A common symptom of this condition is blurry vision. Meanwhile, the fateful August night after which George had been arrested was windy and rainy, and so, there was no doubt in Doyle’s mind that a man whose vision was compromised could not have seen through the storm and murdered animals. Also included was the fact that these killings had continued even after George’s incarceration.

An unlikely alliance

Doyle listened patiently as George detailed other aspects of the trial, his public image as a strange Asian man whose skin colour was different, and how it was believed that Parsis, who worshipped the fire and sun, used to sacrifice animals for prayers, a fact which contributed to George’s conviction. Doyle travelled with George to Great Wyrley, where he inspected the crime scene and interrogated the locals.

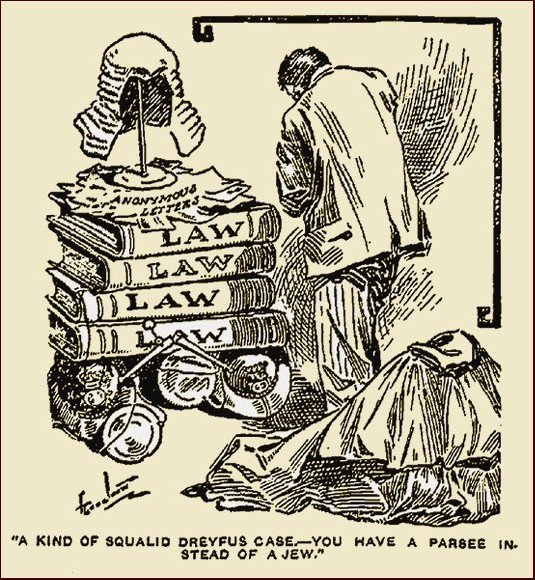

In 2015, the letters of Doyle’s correspondence with the Staffordshire police were made public for the first time. In her book, the Mystery of the Parsee Lawyer, author and journalist Shrabani Basu detailed how Doyle believed that race had a huge role in George’s conviction and how the author attempted to rectify the lawyer’s wrongful arrest and public perception.

Doyle wrote about George’s case for the first time in The Daily Telegraph in 1907, in which he wrote how, in true Sherlock fashion, he had forensically analysed all the “evidence” found against George, how much of the case had been fabricated, and how years of torment that the Edaljis had faced at the hands of the whites had played a role in the blame placed on the young lawyer’s shoulders.

The Home Office of the UK Government cleared George of the previous charges against him but refused to compensate him for the years lost. While Doyle attempted to find the real culprit to help George attain his compensation, the ‘Wyrley Ripper’ was never found. However, several good things came from the unlikely alliance of the famous British author and a young Indian man.

For one, George’s case eventually led to the establishment of the Court of Criminal Appeal (England and Wales). Moreover, George was once again inducted into the Solicitors’ Roll and spent the rest of his life practising in London. George’s was only one of the two cases that Doyle ever took up, and the two remained good friends until the author died in 1930.

Over a century later, discussions around race have only highlighted how George’s incarceration is just one of the many cases of how someone’s skin colour predetermines their guilt or lack thereof in the public’s eye, often without any proof.

In 2013, then Solicitor-General of England and Wales Oliver Heald declared that poor George’s trial had been a farce – perhaps too little, too late.

Edited by Vinayak Hegde

No comments:

Post a Comment