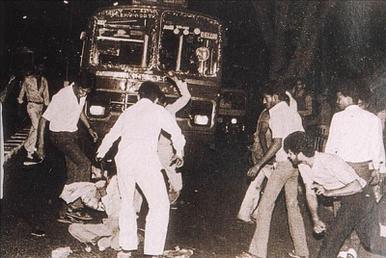

While the Delhi Police was accused of being absent in many instances of bloody carnage during the 1984 anti-Sikh riots, there was one distinguished officer and his small platoon who performed their duties battling all odds. On the morning of 1 November 1984, additional Deputy Commissioner of Police (DCP), Maxwell Pereira led his small platoon of about 25 personnel to protect Sikhs taking shelter at the historic Gurudwara Sis Ganj Sahib in the city’s Chandni Chowk area against a mob comprising of hundreds of rioters.

Despite no backup and with only one revolver at his disposal, Pereira and the small force of brave personnel did everything in their power to prevent the mob from attacking the gurdwara and the people taking shelter in it. Had Pereira not been there, the mob could have desecrated one of Sikhism’s most sacred sites of worship where Guru Tegh Bahadur—ninth of 10 Gurus who founded the Sikh religion—was beheaded on the order of Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, and massacred the people taking shelter in it.

Standing up where it counts

In his book ‘1984: The Anti-Sikh Riots and After’, Sanjay Suri, a former journalist with The Indian Express who was on the ground to document the carnage, dedicates a chapter to how Pereira and his ‘ramshackle platoon’ protected the Sis Ganj Gurdwara from the mob.

Before his heroics at Sis Ganj, Pereira spent the night of 31 October, the day when former prime minister Indira Gandhi was assassinated, guarding Sikhs in North Delhi. His teams were escorting members of the community to their homes.

In the early hours of 1 November, he was called by the Police Commissioner to oversee security for the new Prime Minister, Rajiv Gandhi, at Teen Murti Bhavan, where Indira Gandhi’s body lay. Once there, however, Pereira found himself simply waiting as reports came from his wireless operator of Sikh-owned establishments being attacked.

Upon receiving news of a fire at Bhagirath Place, a wholesale electrical goods market across the Red Fort and a few minutes away from Sis Ganj, Pereira insisted to the Commissioner that he could no longer stand around while there was no one to handle the situation.

“I left sometime between 9 am and 9.30 am. I reached Red Fort in my jeep. We were a total of six or seven people in the jeep. They had their hand weapons only—short batons,” Pereira tells Sanjay Suri in a conversation for his book.

Upon reaching the Red Fort, he met with the local police post in charge, who had about two or three people with him. With just 10-12 police personnel, they marched towards Bhagirath Place in an attempt to disperse the crowd assembling there. No additional manpower was sent to the location by Delhi police at that time.

After marching through Bhagirath Place, the officer and his men headed straight to the Gurdwara area as they saw a mob assembling and coming towards it. Meanwhile, he had to deal with another issue. “An intention to attack the Gurdwara was becoming evident, and the inmates of the Gurdwara were not taking this kindly. They were coming out of the gates of the Gurdwara, brandishing swords in the air, ready for confrontation,” he tells Suri.

As Pereira arrived on the spot, he assured inmates of the Gurdwara that he would take full responsibility for protecting them. Meanwhile, he spotted frightened Sikhs hiding in nearby lanes and by-lanes who were heading towards the Gurdwara, which stood as the only sanctuary available to them. Pereira’s team escorted them into the Gurdwara, and he remembers reuniting a husband with his wife days after the incident.

In front of the Gurdwara was a police post called the Fountain Chowk, which Pereira and his men had taken over.

“We had taken over that chowk because we had handed over the Kotwali police building to the Gurdwara as per some pact with the Shiromani Akali Dal because their Guru was martyred in that Kotwali. (‘Kotwali’ literally means ‘police station’. That police station – called simply ‘Kotwali’ – was located earlier within the compound of the Gurdwara),” recalled the officer in Suri’s book.

Fortunately for Pereira and his team, at the Fountain Chowk police post, there was the SHO Kotwali, who had a small force with him. That allowed the police there to stand their ground and keep the mob away from the Gurdwara. “One group of people was advancing from the Chandni Chowk town hall to one side and the other was coming from the railway station (to the north of the Gurdwara),” recalled the officer.

So he had about 25 police personnel, a small platoon and no armed party support, to control the situation.

After initially dispersing a mob in Chandni Chowk, where rioters were burning down Sikh shops, Pereira and his small platoon set up positions in and around the Gurdwara area. As the menacing mob pushed closer to the Gurdwara, his small force acted instantly.

“Once or twice we did warn them of action, we set up mob control banners, we launched our mob control drills and all the usual requirements, we had the shields, we had the long batons. We had by then a half-section of a tear smoke squad from the district unit which was not with the rest of the forces that were at the DCP’s command. I managed to bring that into the Chandni Chowk area from the district lines. There was half a section of the reserve (tear smoke squad) there,” he said. Meanwhile, they fired a couple of rounds of tear smoke to disperse the mob, but it grew stronger with members shouting ominous slogans.

By this time, the small police force couldn’t stop the mob from burning down Sikh shops. Pereira had no choice but to warn them that he would open fire if they came any closer.

Even that warning didn’t work against the mob.

“Then I ordered the firing from my revolver. I was not carrying the revolver, my gunman was carrying it. His name is still alive in my mind, Head Constable Satish Chandra. He was on my staff throughout. He opened fire, and one person dropped dead. That created a tremendous impact. I couldn’t help myself. Then and there, on the microphone, I announced a reward of 200 rupees, a meagre 200 rupees, for opening fire. I told the crowd there will be more to follow if anyone ventures further. That is the sum and substance of what happened,” he said.

He had managed to disperse the mob with just a single shot from his revolver at close range. Meanwhile, the armed police force stationed for the district was “locked into service of DCP SK Singh”.

“The small force posted at Fountain Chowk was on its own until the little band led by Pereira turned up—on its own without any direction from any top police officer other than Pereira himself. So it was this ramshackle platoon drawn from policemen in a single jeep, from a police kiosk, and then from an understaffed police post at Chandni Chowk, that Delhi Police had found to defend the most historic Sikh centre of worship in Delhi,” writes Suri.

Under the circumstances, it was a risky move. Things could have gone very wrong rather quickly. After all, the crowd was close enough to sense whether the small force was carrying more guns or not. If the mob sensed that the small force didn’t have any, they would have moved forward and overwhelmed it. There was indeed an element of good luck.

Even though Pereira had repeatedly informed the police control room that he had opened fire and killed a person, there was radio silence.

Performing His Duty

Of course, this wasn’t the end of the trouble at Sis Ganj, but by that time, he was able to mobilise “whatever was left of the manpower”. He deployed officers in plain clothes to infiltrate mobs, who would relay information to him. Meanwhile, there were other terrifying incidents of violence emerging out of areas in North Delhi like Azadpur, Gulabi Bagh and Jahangirpuri, and Pereira was busy issuing directions to his junior officers to act decisively.

Writing for the BBC, Pereira says, “None of these officers and men of the north district who controlled the riots and saved [the] lives of many Sikhs got any recognition or reward for doing their duty. This is in stark contrast to some of our colleagues elsewhere who even received gallantry medals for killing scared and paranoid Sikhs who unfortunately opened fire on the police while trying to defend themselves.”

Talking about the decision to open fire, the officer writes that he was “duty-bound to save the victim” even if it meant killing the aggressor.

He concludes by saying, “There is a lot of comment that the police were waiting for clear-cut orders from a totally confused and shell-shocked government and police leadership. I firmly believe that no policeman needs orders from above to act correctly and timely, as warranted, in times of such need. If the concerned policeman has dithered and procrastinated, I believe he is guilty of dereliction of duty, if not of actively conniving with the perpetrators.”

Sources:

1984: The Anti-Sikh Riots and After by Sanjay Suri (Published by HarperCollins in July 2015)

‘The Indian police officer who saved Sikhs during the 1984 riots’ courtesy BBC

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

No comments:

Post a Comment