From booking vaccine slots to finding the right food for your mood, tracking court case schedules, sending gifts, and shopping online — the mobile application industry has taken the world by storm and created its own ecosystem.

An app makes our lives easier, flexible and more informed anytime, anywhere. Sensing the appetite of mobile applications and their wondrous benefits, Puducherry District Collector, Dr T Arun has developed an app of his own.

This one is unique in the sense that it has resulted in the revival of 198 water bodies including ponds and lakes, as well as a stretch of 206 km of canals.

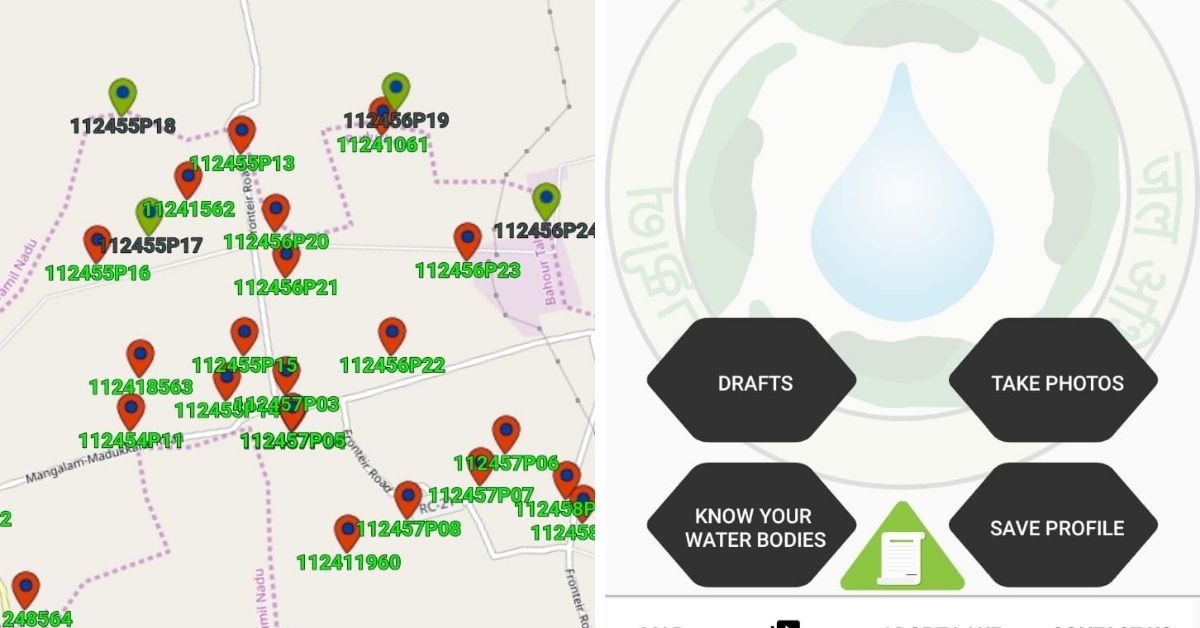

Called ‘Neer Padhivu’, the app is a first-of-its-kind in India to digitalise water bodies with geotagging, unique ID numbers, GIS on ponds, tanks with latitudes and longitudes coordinates. Each water body is updated with the status of groundwater levels, moisture content of soil and size via remote sensing satellites.

“The application, developed by the CSIR (Council of Scientific and Industrial Research) – National Environmental Engineering Research Institute, has not only helped streamline the rejuvenation process, but is also ensuring that people don’t dirty or encroach the water bodies. The digital world can surprise you in many ways, and we are glad to bring a modern solution to the district’s severe water crisis,” Dr Arun tells The Better India.

The restoration process was started under Puducherry’s Neerum Oorum (Water and Village) Scheme to adopt, renovate and conserve water bodies.

Digging through archives

Monsoons are the main source of water for the district, which is situated on the South East Coast of India. However, due to climate change and erratic rainfall patterns, farmers and industries have turned towards groundwater tables to meet their needs.

Due to rampant extraction, the Central Ground Water Board (CGWB) categorised Puducherry as a water-stressed district. To make matters worse, a large number of trees were uprooted during the Thane Cyclone in 2011, as well as during other yearly cyclonic storms.

“It is not possible to change rainfall patterns and suddenly recharge groundwater tables. So we found a solution in ponds and lakes that were either lost, had dried, or been overrun with waste, debris and encroachments. This would also help tackle the menace of saltwater intrusion. Since we live in coastal areas, the saline water mixes with the groundwater. This can be avoided by raising the levels of water tables,” says the 2013-batch IAS officer.

The project is being carried out in collaboration with various stakeholders including corporations, hotels, resorts, schools, NGOs and locals. Dr Arun says community ownership and digitalisation of water bodies are the keys to successful implementation. He shares the process and its challenges, surprises and impact.

Upon digging through old records of Puducherry’s water channels, Dr Arun learnt about feeder channels that connect the district’s water bodies. Most bodies are interconnected, which means that the main water feeder channel feeds others by conveying water from one pond to another during monsoons. The records also stated that there are over 600 water bodies across 150 villages. However, due to a lack of location records, many lakes and ponds had been lost.

“We mapped water bodies by reading history and talking to elderly people. We identified many lost water bodies due to siltation and encroachment. For example, Villianur Commune Panchayat had 27 waterbodies on their list, but our search showed 71. We were surprised to identify 3-4 water bodies per village, which is a sign the district was once water-abundant,” says Dr Arun.

The administration also dealt with illegal encroachments around ponds and lakes by farmers and shop owners. They were asked to vacate the land and restrict their farming activities.

Once all the water bodies were identified, the team spent the next two months geotagging the exact locations, water levels, size and allotted unique ID numbers.

Building a community endeavour

Dr Arun then roped in various stakeholders including corporates, NGOs and schools in the rejuvenating process. There were two reasons for this.

“If people participate in the cleaning process, they learn about the benefits of water bodies and will be mindful of dirtying them in the future. Some communities have pledged to monitor water bodies for life. Another reason was to save the Government Exchequer — the entire project is funded through CSR activities. Participation by schools was a surprise element. They learnt about our project through our awareness programmes and wanted to involve their students,” says Dr Arun.

Every stakeholder adopted one or more ponds and lakes to desilt and clean with JCB and through manual work. Around 30 temple authorities also came forward and cleaned the ponds inside their premises.

“Dr Arun approached us and presented a systematic plan to clean water bodies. He also extended financial help. We were able to clean 55 ponds. This is the first time a large scale project like this is being implemented to benefit the people and environment. Without Dr Arun’s support, it would have taken us longer to carry out cleanup drives,” Ashok, founder of Neer Nilai Pathukappu, an NGO, tells The Better India.

Since 2019, close to 60,000 volunteers have been involved in the project, from clearing garbage to planting trees around water bodies. Under the administration’s afforestation initiative, 58,000 saplings have been planted around the water bodies to help in underground water percolation, as well as for beautification.

According to a report by CGWA, groundwater tables across the district have risen by 15 feet since the project’s inception. This has ensured a regular supply of drinking water to locals and irrigation to farmers, says Dr Arun. Another visible change is an increased presence of smooth coated-otters in water bodies such as Kannikovil, Veerampattinam and Poornankuppam.

While the pandemic has slowed down the activities, Dr Arun hopes it will pick up once the cases dip to zero.

Edited by Divya Sethu

No comments:

Post a Comment