From the ’50s till the ’70s, Kolkata (then Calcutta) witnessed a surge of refugees after the Partition of India. These were decades of chaos but also of a social and cultural awakening, where different sections of the society were out on the streets to demand food, wages, housing and other basic rights. These varying sections—students, refugees, the working class and more—joined hands in the face of political upheavals and the surge of the Naxalite movement.

Amid the changing landscape of this city emerged a group of young men, armed with the drive to raise their voices that could connect even the most varying sections of society through a single medium — music. This helped form India’s first rock band, Moheener Ghoraguli (Moheen’s horses). The name was picked from Jibanananda Das’s poem Ghora, where a line of the poem says, “Moheen’s horses graze on the horizon, in the Autumn moonlight”.

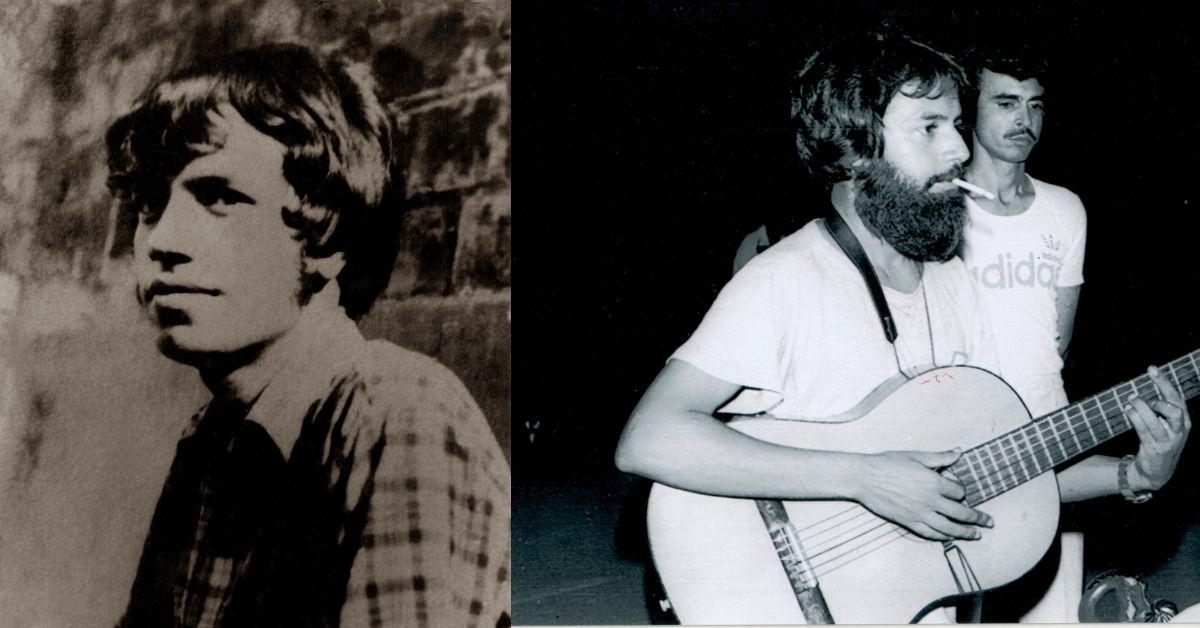

At the helm of this musical movement was Gautam Chattopadhyay, who formed the group in 1975 with his brothers Pradip and Biswanath (Bishu), cousin Ranjon Ghoshal—who picked the band’s name—and friends Tapas Das, Tapesh Bandhopadhyay (who was later replaced by Raja) and Abraham Mazumder.

“The music had elements of rock, jazz, blues and Western classical music; folk elements from Bengal were also very visible in the music they made,” Gaurab Chatterjee, Gautam’s son, tells The Better India. “My father had a huge palette for different kinds of music, where he would try to listen to new forms all the time.”

Moheener Ghoraguli was born in Gautam’s backyard and as is the typical origin story of legendary bands, it was just a simple coming together of young boys who were united in their love for making good music. “For my father, a band from India, or even Bengal, had to sound like it belonged to the country instead of blindly aping the West. Having one’s own elements meant a great deal to him,” Gaurab notes.

At this time, Bengali music was defined more or less by commercial and/or Bollywood music. “These were sweet, romantic songs, or film songs, whereas the band was talking about social issues through a different composition altogether. So it was something different for the masses,” says Gaurab.

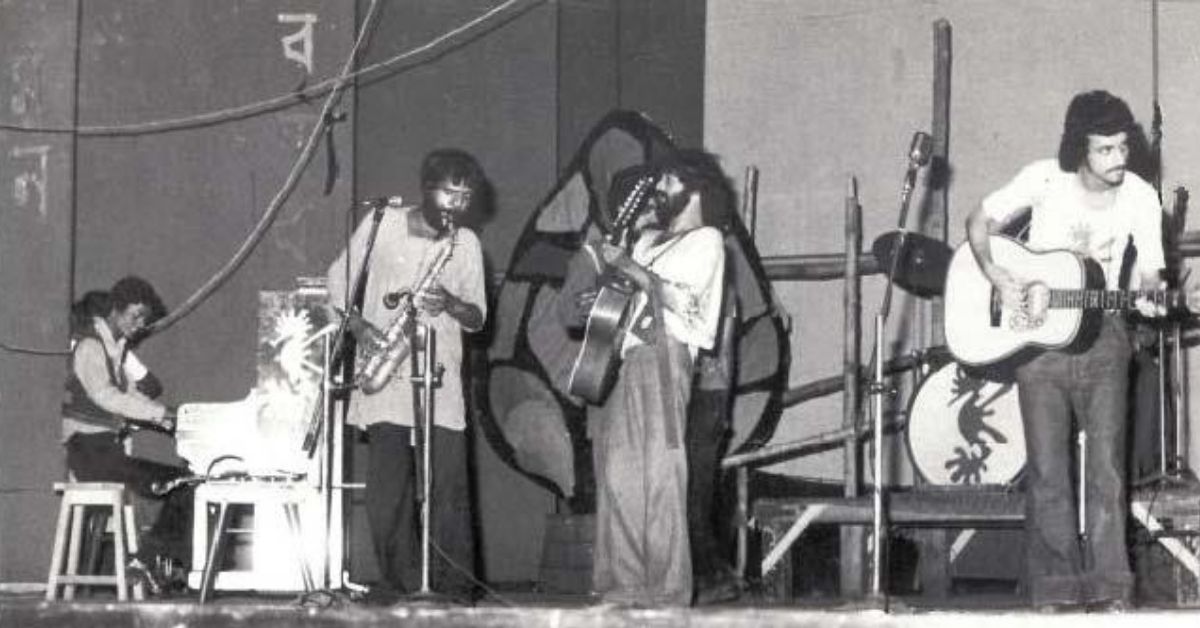

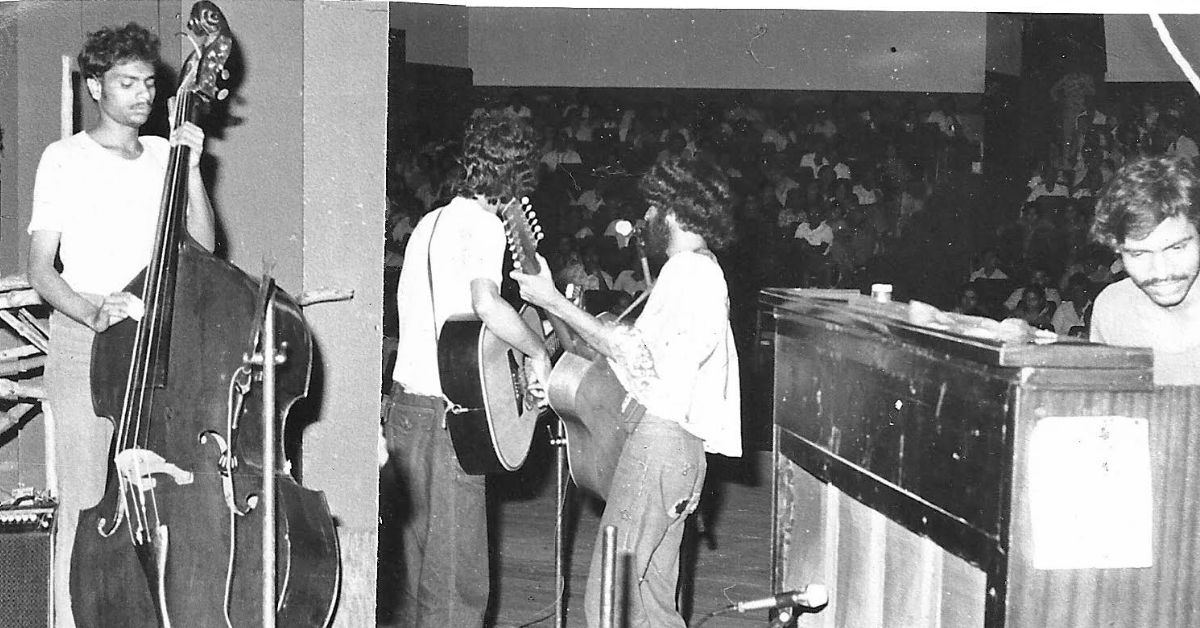

The group began with performances at small gigs throughout Kolkata. But audiences were unaccustomed to this new sound. Commercial success was a slow and uphill battle, but regardless, the band produced three albums of wonderful music.

Talking about a few songs and their meanings, Bishu Chattopadhyay, Gautam’s younger brother and member of the band, says, “We wrote this song called Shono Sudhijon [Dearly beloved]. Roughly translated, the lyrics meant, ‘Oh city dwellers, listen, we wake up with nightmares everyday thinking about your injustices and neglect—oh dear people, as if your life is the precarious ‘Charak’ performers going around with your back facing the sky—listen dear beloved people, we are with you’.”

He adds, “Then there’s Haay Bhalobashi [We love with sadness], where we say, ‘We love getting immersed in the countryside, the nature, a run in the moonlight with distant hills, paddy fields, a boat ride or sitting by the window with a book of poems.”

He further adds, “We love Picasso, Bunuel, Dante, listening to the Beatles, Dylan, Beethoven. Love listening (live) to Ravi Shankar or Ali Akbar and returning home in the foggy morning. Yet none seems good or satisfying, there is always sadness underneath. None makes sense when we notice oppressed peasants or workers sweating in the fields and ports. We wait for the bright day when we all can love life together’.”

Haay Bhalobashi

Gaurab says his father spent a lot of time with the Bauls, a group of religious singers from the Bengal region. Moheener Ghoraguli often described their style of music as ‘Baul jazz’. “My father was quite influenced by the time he spent with the Baul singers. Members of the community also came to perform with the band during the Kolkata International Jazz Festival around ‘79 or ‘80,” he says. “One of the first examples of folk fusion in a band came from Moheener Ghoraguli as well,” he says.

Describing the reception that Moheener received and the struggles they saw, Bishu tells The Better India, “We were not given opportunities to express ourselves the way we wanted. We wanted equal sounds for all our instruments, as well as vocals but engineers at the recording studios were often against that. There were many times where sound engineers or recording studios would think they were one up on us — we were nobodies at the time. Moreover, the so-called ‘established Bengali community’ was still holding onto Tagore songs, and a lot of footage was given to only gifted singers or traditional musicians. I think people were afraid to publicly support something different.”

“Also, none of us had money,” he laughs. “It’s not like we were going on these giant tours. We used to often jokingly ask, ‘How do you make Rs 5 lakh? Possibly by starting out with Rs 10 lakh of your parents’ money’.”

In 1981, Moheener Ghoraguli parted ways. When I ask if their struggles to find commercial acceptance played a role in this, Bishu says, “Well, yes, if we had been given more opportunities, maybe things would be different. It wasn’t because of any disagreement. It was more situational. So many of us left, and only Gautam da chose to stay back. But of course, if people listened to our music, we would have stayed — who wants to leave their home, friends, and family, and move away?”

Other members went on to pursue careers for a bit, while Gautam diversified into filmmaking. Interestingly, during this period of disbandment, many Moheener Ghoraguli songs survived across different college campuses in Kolkata as an oral tradition. “These kids didn’t even know whose songs these were, but they’d sing it anyway,” Gaurab says.

He further recalls that with the advent of MTV in the ’90s, when the father-son duo would switch on the channel, Gautam would be fascinated with the music videos he saw. “He wanted to make something similar and created a three-part miniseries of music videos which got sanctioned by Doordarshan,” he recalls. “He got new people to sing some of his post-Moheener songs, shot videos for them and that’s how a collective of great music came about.”

And that is how, in the ’90s, Moheener Ghoraguli emerged again, but this time as a collective of musicians. With his friends in a publishing house named A Mukherjee, Gautam released a compilation called Abar Bochhor Kuri Porey (Again, After Twenty Years) in 1995 at the Kolkata Book Fair. Gaurab says, “This was Moheener Ghoraguli’s second phase, which was a collective of musicians and artists that my father liked.”

A notable song on this album was Prithibi Ta Naki Chhoto Hote Hote, a commentary on the human tendency to be glued to the television to a point of humanity’s own downfall. This song was later recreated by composer Pritam in his song ‘Bheegi Bheegi Si Hai Raatein’ for the 2006 movie Gangster. The collective released three more albums — Jhora Samoyer Gaan, Maya, and Khyaapar Gaan.

Subrata Ghosh, a member of Gorer Math and an active member of this movement, tells The Better India, “This movement involved not just musicians but also artists and filmmakers, to encapsulate different forms of expression. We weren’t making this music to be famous, but to express ourselves. We didn’t know the kind of impact we were making. We didn’t have a lot of financial help on our side. A lot of these albums were sold in black but it gave us an idea of the impact. Gautam da used to say that when you find your cassettes being plagiarised or sold in black, you understand the popularity of your music.”

“There were no interviews or press releases,” Ghosh notes. “Our impact was all word-of-mouth. For example, one of the members of our collective was a radio jockey, who’d often play Prithibi during his segment. Our music started selling like hotcakes and we did some concerts but not too many.”

Also involved with the collective was Arunendu Das, a pioneer of 20th century alternative Bengali music. While Das never intended his songs to reach a wider audience, Gautam was so moved by his music that he included many of his songs on the collective’s albums.

Gautam died suddenly of a heart attack on 20 June 1999, and his demise left a deep scar on the Bengali music fraternity. Ghosh recalls, “I’d left for Japan for some work, and I used to call him and keep in touch regularly. I remember, on the day he passed, I tried calling him several times but the call would not connect. I received the news the next day. The whole Calcutta music fraternity came to the house to pay their respects. I was still in Japan at the time, and when I received the email of his death, I called his wife. The two of us broke down on the phone, and in the background, I could hear Baul singers singing in mourning. I returned a few years later, but Calcutta has always been empty without Gautam da.”

Shortly before his death, Gautam had visited a Naxal-infested area to interact with Karbi youth, and organised an opera on the community’s folklore called Hai-mu. Around 300 Karbi youth performed here, and the event was a grand success, inviting the community’s adoration for Gautam. He had also been working on a movie in Karbi language, which remains incomplete due to his sudden death.

Bishu, who now is a member of a jazz band in the US, says, “Gautam da was the most popular brother among us, from when we were very young. Our life was always a little public because of how many people noticed his talent. He taught me that you can make music the way you want, and that it’s okay to be adventurous. There’s no need to conform. He never believed in doing things the way everyone else expected him to. For example, people may expect that the best voice in the band should sing a particular song, but he would go ahead and pick someone else because that has another kind of creative quality. He was a leader, he knew how to bring people together. He could zero in on the best abilities of people to highlight them in the best way possible, just to try out seemingly unthinkable ideas.”

Today, remaining members of the original band include Pradip, who resides in Kolkata and experiments with city and natural sound, as well as abstract theatre, Bishu, who lives in the US, Abraham who runs a music academy, and Tapas who helms a band. Tapesh lives in Kolkata and Raja in the US. Ranjon passed away in 2020, a year after he was accused during #MeToo for sexual harassment. Band members and Gaurab have, in the past, emphasised that they stand in solidarity with the victims who came out in the movement.

Shono Sudhijon

Encapsulating the present world impact of the band, Ghosh says, “Earlier, there was this impression that people who make music or those who are artistic in general, are God-gifted. Commoners couldn’t do that. But with this movement, people started believing more in themselves, and looked at it as a form of expression, something that everyone is capable of doing.”

Bishu says, “I think Moheener Ghoraguli instilled a sense of pride in your own language. So many young talented singers today are making so much more new music, and if Gautam da was alive today, he would be so happy.”

You can watch the video that the ’70s band members created in remembrance of Gautam Chattopadhyay here (credit: Bishu Chattopadhyay) and a video of Abraham’s students covering Haay Bhalobhashi here.

Edited by Yoshita Rao

No comments:

Post a Comment