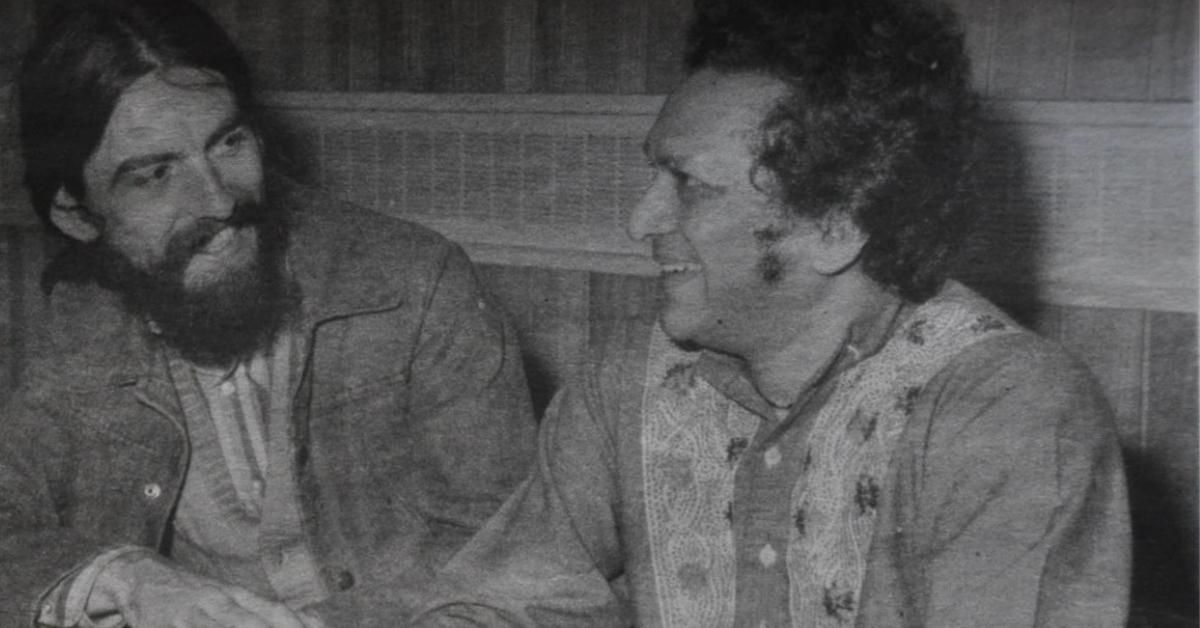

Perhaps one of the greatest unions in the history of music is that of Pandit Ravi Shankar and former Beatle George Harrison. Their meeting in 1966 birthed an instant yet unlikely connection and albums full of wonderful music. The two came together despite differences in their age, cultures, backgrounds and even social status, but developed a solid camaraderie that would last till Harrison’s death from cancer in 2001, with Shankar being at his bedside with the rest of his family.

This historic union took place in the house of portrait painter and novelist, Patricia Clare Angadi, and her husband, a relatively lesser-known Indian man named Ayana Deva Angadi. While Patricia remains “best known as the person who introduced Harrison and Shankar”, her ex-husband’s name remains more or less missing from the mentions of this famed encounter. However, his efforts to popularise Indian music, yoga and dance in the western world paved the way for artists such as Pandit Ravi Shankar and Akbar Ali Khan.

So who was Ayana Deva Angadi?

‘Shining hope’

Born in 1903 in Jakanur village in Mysore State, now in Karnataka, at the age of 21, Ayana went to London in 1924. His goal in London was to finish a degree he’d started back home at Bombay University, but he soon realised that normal jobs were not for him.

Instead, he became increasingly involved in political activism and wrote several articles and journals under the pseudonym Raja Hansa. He joined the Labour Party and wrote on Japanese imperialism, fascism and capitalism. His deep interest in politics meant that he was never really employed long-term, and flitted in and out of radical left political circles for most of his youth.

At the onset of World War II, Ayana met his future wife, Patricia. In Ray Newman’s Abracadabra: The Complete Story of the Beatles’ Revolver, Ayana’s son Shankara said, “He was very striking looking, with long hair and aquiline features, and that went to his head. He…lived as a kind of toy boy to various socialist women for ten years or so. Then he met my mother. One version of the story is that she saw him from the top of a bus on Regent Street and said, ‘I have to paint that man’.”

Patricia and Ayana’s union was met with disdain, particularly because she belonged to a well-off family and he had given up his wealth for a life of activism. Alongside, of course, were differences of race, which contributed to Patricia’s parents’ overall disdain for Ayana. Regardless, the two married in 1943 on Labour Day in a registrar office.

In an obituary upon his death, The Guardian wrote that he came from a large family and was their “shining hope”.

The assimilation of Indian culture with the UK

In 1946, the couple founded the Asian Music Circle in their home to promote Asian culture and music in Britain. From hereon, the Angadis began shaping Indian arts as something more than just a fancy of the elite left circles of Britain, and more towards something that the masses could enjoy.

“…In the mid-1950s, Patricia and Ayana Angadi began the slow process of bringing Indian art to the chattering classes. They imported musicians and dancers, putting them up and, in their own chaotic way, organising and promoting tours. Some musicians stayed, forming the core of a musical “repertory group” who, as well as performing in their own right, would back visiting celebrity musicians or hire themselves out to record and film companies,” writes Newman.

This “repertory group” included renowned violinist Yehudi Menuhin, English classical composer Benjamin Britten, and world-famous yoga teacher B K S Iyengar. In fact, in the case of Iyengar, from the day he held a session in the Angadi’s north London home, the face of yoga changed in the UK forever — it became the popular discipline it is known to be today.

Around 1955, Menuhin had become the president of the AMC, which had started gaining massive notoriety for its performances. He had gained funding to stage a giant music festival — Living Arts of India Festival — in New York, and his first choice was Pandit Ravi Shankar, who he had previously met at a concert in New Delhi in 1952. However, Shankar was forced to turn down the opportunity owing to problems in his marriage, and the festival instead called in Sarod player Ali Akbar Khan.

This festival by the AMC marked the first formal recital of Indian classical music in America. Owing to its massive success, the centre organised for Khan to play in London and was finally able to bring Ravi Shankar alongside. This marked the sitarist’s first western concern, held in October 1956. The year also marked the entry of famed sitarist Vilayat Khan to the UK for the first time.

Angadi’s introduction to The Beatles happened particularly during the recording of ‘Norwegian Wood’, which featured Harrison playing the sitar. The story goes that during a recording session, one of the sitar strings broke, and Harrison made contact with Angadi in search of a replacement. In an interview for Newman’s Abracadabra, Shankara said, “There’s a story in my family, which I don’t believe, that my father had never heard of the Beatles. He was heard shouting into the telephone: ‘Yes, but Ringo who?’ As luck would have it, we did have some sitar strings in the house, and the whole family went down to the studio at Abbey Road and watched them record, from behind the glass. My mother drew several sketches of them recording ‘Norwegian Wood’, which are still in the family.”

As Harrison became further involved with the Asian Music Circle, he was introduced to Ravi Shankar, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Returning to his roots

It was due to Angadi and the AMC that Harrison, and subsequently The Beatles’ music, was so influenced by Indian culture. Many of the Beatles’ tracks featured Indian musicians from the AMC, in particular, Anil Bhagwat, who played the tabla for ‘Love You To’. He received a credit on the album sleeve for Revolver, which was a rare occurrence for an “outsider”. Songs on St. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts, including Within You Without You, feature AMC members on the dilruba, swarmandal and tabla as well. In 2017, a few of these musicians, who had remained unknown up until then, were tracked down for a live performance.

Some time in the 70s, Angadi and Patricia split, leading to the dissolution of the AMC. Angadi’s roots beckoned him home, and he returned to Jakanur and immersed himself in rural development projects in his homeland. “He came to believe that his theorising in London had served its purpose but had done nothing for his home village,” journalist Reginald Massey said, writing for The Observer. “And so he went back to Jakanur and organised rural upliftment projects. Houses were built, a school was started, electricity was brought in and a well was sunk. He got buses to service the village.”

On Angadi’s death in ‘93, Massey further noted, “The death of Ayana Angadi, aged 90, will be mourned by all Britons and Indians who value mutual respect, tolerance, understanding and cultural exchange. He was a man of immense energy whose crusading work, often behind the scenes, influenced the great and the good. The acceptance of Indian culture — the art, music, dance, or yoga — in the United Kingdom today is due in no small measure to Angadi’s endeavours.”

Edited by Yoshita Rao

No comments:

Post a Comment