Around 30 km from Darjeeling lies the verdant and organic 150-year-old Selim Hill Tea Garden, spread across 973 acres, of which approximately 450 acres come under tea bush cover. Owned by 23-year-old Sparsh Agarwal’s family since 1990, the Selim Hill Tea Garden is one of the 74 operational tea gardens in the region selling the world-famous Darjeeling Tea. However, like most tea gardens here, which are dependent on the international export market, Selim Hill was barely breaking even.

After the end of each year, Sparsh’s family, who are based out of Kolkata, would hope for some miracle in the export market to reverse the tea garden’s fortunes. When COVID-19 struck in March 2020, it broke the proverbial camel’s back. After all, the pandemic had destroyed their chances of exporting their first (spring) and second flush (summer). Flush refers to the period when tea plants grow new leaves that are harvested. The first two flushes generate the highest amount of revenue for tea gardens.

With options running out, Sparsh’s family in April 2020 considered selling the tea garden.

Meanwhile, Sparsh, a former student of political science and international relations at Ashoka University in Sonepat, Haryana, was working with the Centre for Policy Research, a Delhi-based think tank.

He was never interested in getting into the family business. But when he told his friends that his parents were thinking about selling their tea garden, something changed drastically.

“When I was in school and college, I would often bring my friends to Selim Hill during the holidays. They have fond memories of this place and the people here. When I told them of the family’s decision to sell Selim Hill, my friends asked whether they could come on board and help revive it. That’s when Ishaan Kanoria (24), an investment banker, and Anant Gupta, a graduate of the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), came on board. Given our memories associated with the area, we decided to give the revival process one last try,” recalls Sparsh, speaking to The Better India.

But it was difficult convincing his parents, who eventually agreed on one condition. Sparsh and his friends would have to dedicate all their energy towards reviving Selim Hill.

After agreeing to this proposition, Sparsh and Ishaan established Dorje Teas, a venture which seeks to radically change the way Darjeeling tea is marketed and sold. Under their unique subscription model, consumers need to pay just Rs 2,100 for an entire year’s supply of fresh and organic tea.

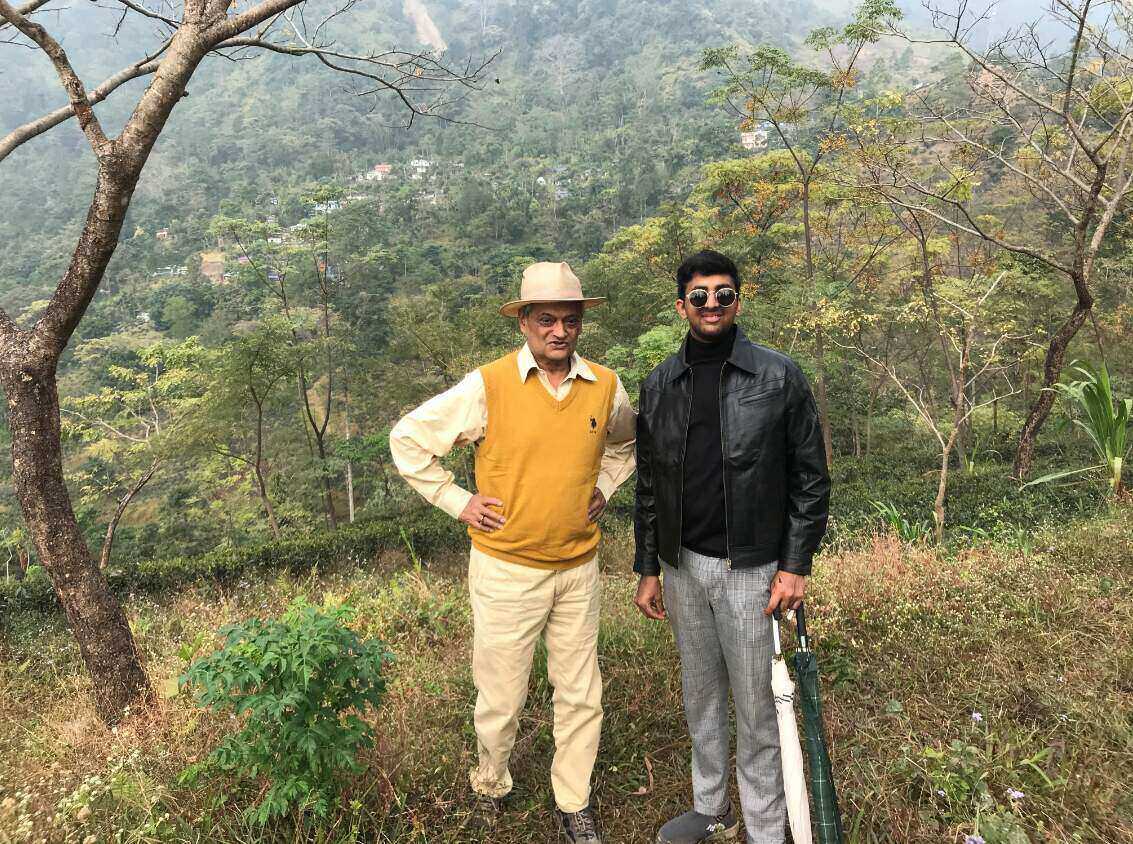

They built Dorje Teas under the mentorship of 74-year-old Rajah Banerjee, a legend in the Darjeeling tea business, former owner of the Makaibari Tea Estate in Kurseong and pioneer of the organic movement. “He is also an investor in the company, our brand ambassador and the elder statesman guiding us through the entire process,” Sparsh adds.

Meanwhile, under Rajah’s chairmanship, Sparsh and Anant have established the Selim Hill Collective, which seeks to “reimagine the space of the tea estate, by moving away from the model of a commercially exploited plantation to that of an inclusive and sustainable garden”.

Why the Darjeeling Tea industry suffers

From May to November 2020, Sparsh and Ishaan set out to understand the local tea business, why it was suffering, and formulate possible solutions to these issues. After speaking to Rajah, conducting their own research and visiting other tea gardens in the region, they figured out four major reasons why Darjeeling tea industry was suffering.

1) Climate change: The effects have been felt particularly over the course of the last decade with changing rainfall and wind patterns. The tea is produced over a period of about seven and a half months because that’s when Darjeeling gets her rains. However, Sparsh and Ishaan realised that this period of rainfall had shrunk to about five and a half months.

Further, as a result of climate change and factors related to it, the region is seeing irregular droughts and unnatural landslides. Other macro factors include greater prevalence of dams, which is leading to more seismological activity including earthquakes.

2) Beholden to the export market: Tea gardens here don’t focus on the domestic market. They also don’t market all four flushes as unique items.

“There has been a lot of inertia within the Darjeeling tea industry about how we market ourselves. We don’t focus on domestic sales and make it affordable for Indian customers. Many are stuck in their old ways. The Darjeeling tea industry needs to come out of this bubble and move forward. The many industry veterans we spoke to said that without centering on the export market, our tea garden would shut down. But we have been exporting for the past 30 years, and are still on the verge of collapse,” says Sparsh.

3) Archaic systems of management: Besides an anachronistic system of grading and sorting tea leaves for the export market, tea gardens continue to operate on a colonial hierarchical management style. Sparsh admits that past generations of his family have benefitted from this, but believes it’s not sustainable in the long run.

4) Cheaper Tea from Nepal: During the crippling 104-day strike in the region demanding a separate Gorkhaland state, many tea gardens lost a lot of their produce. To fill in the domestic demand, traders began importing cheaper tea from Nepal and took over a large chunk of the market. After all, half of the Darjeeling tea is consumed in India. To win back some of the market, Dorje Teas has embarked on a social media strategy showing consumers where exactly their produce is coming from. “You need to support local communities, otherwise this is going to collapse,” he adds.

Subscription model: Breaking the mould

This model hinges on seasonal harvests in spring (first flush), summer (second flush), monsoon (third flush) and autumn (flush). While the first and second flush get exported, the latter two are sold in India. The monsoon and autumn flush don’t fetch a higher price than their spring and summer counterparts because of how the Darjeeling tea industry operates.

“You have tea garden owners, managers and the larger associations that publicly say monsoon and autumn flush teas are of lower quality. Through our research, we found that all four have their unique taste, aroma, flavour and story. The monsoon flush tea, which gets the worst rap, is unique because it gives you a bold colour, smoky taste, and drinkers can actually add a drop of milk in it as well. Just imagine the uniqueness of a garden which can generate tea in the spring time which is so floral that you don’t even have to add sugar and months later produce tea in which you can add a drop of milk,” Sparsh explains.

Anyone can sell the first and second flush. That market already exists. The problem for tea gardens in Darjeeling is their inability to sell their autumn and monsoon flush. So, Ishaan and Sparsh decided to focus on selling the latter, and thus create a subscription model which allows consumers/patrons to book their annual supply of tea.

“Our promise is that we will deliver the freshest possible tea. As soon as you place the order, we roast the tea leaves, pack and send it to you. This way we are able to average out the prices. Monsoon and autumn flush prices are lower than their spring and summer counterparts. But the Indian customer is anyway not getting the first and second flush, which are exported. First flush teas are sold at anywhere between Rs 5,000 to Rs 10,000 per kg. In our model, if you book your annual subscription at Rs 2,100 per kg, you get 250 g each of the four flushes, including the monsoon flush, which we specially roast, in three-month intervals. After all, 250 g makes about 100 cups of tea,” he claims.

If customers want to drink more, they can always opt for getting these packets delivered every month. At 2,000 per kg for the entire year, this becomes a valuable proposition. Subscribers become supporters of the tea garden and acquire quality and organic farm fresh tea at their doorstep. Going further, Dorje Teas has created a tea community.

“We’ve created a Tea Club where, every Sunday, we send subscribers updates of what’s happening in the garden, blog posts, pictures of certain bird species that might have been spotted and organise speaker sessions called Echoes. If this model works for us (we need 50,000 customers in the first year), it can become a model for others,” he explains.

Another way in which Dorje Teas has broken away from conventional practices of the tea industry is by doing away with export-market oriented grading systems at their heritage factory. In the tea industry, leaves are typically divided into four grades – Whole Leaf, Broken Leaf, Fannings (deposited in tea bags), and Dust (also deposited in tea bags).

To establish these grades, tea gardens employ machines called breakers, which essentially use metal to cut down the tea leaves to different sizes. These leaves then go into different troughs, which end establishing the four grades of tea leaves, and are eventually packaged.

“Looking back at how estates in Darjeeling manufactured tea 40 years ago and undergoing an extensive tea tasting process from different gardens, we realised that we don’t need the breaking process. In fact, breaking reduces the quality of tea and leaves behind a metallic tinge. After the tea comes out of the drying oven, we perform a simple hand sorting process to remove some of the stem. There is no crushing or breaking. There is very little handling and that leaves us with the original taste of Darjeeling tea,” Sparsh notes.

Selim Hill Collective for the community

Established during the 150th year anniversary of tea garden last year, the purpose of the Collective is to “create a model for a more sustainable and just tea garden, where workers get their due, the biodiversity is preserved, and Selim Hill becomes the site of a cultural renaissance for Darjeeling,” notes a blog on the Dorje Teas website.

There are about 1,000 households in Selim Hill, of which 350 are directly associated with working on the tea garden. While Sparsh’s father helped set up a proper sanitation system for its residents, the Collective is looking to address the problem of overall waste management since the area does not have a proper municipality.

Currently, Dorje has launched a large-scale afforestation campaign at Selim Hill to help maintain soil cover and prevent landslides. They have already planted about 300 saplings in partnership with the local forest department. For every subscriber, Dorje will contribute to the Collective’s campaign to increase tree cover at the garden. Within wildlife conservation, they’ve also started doing a proper taxonomy of bird species in Selim Hill.

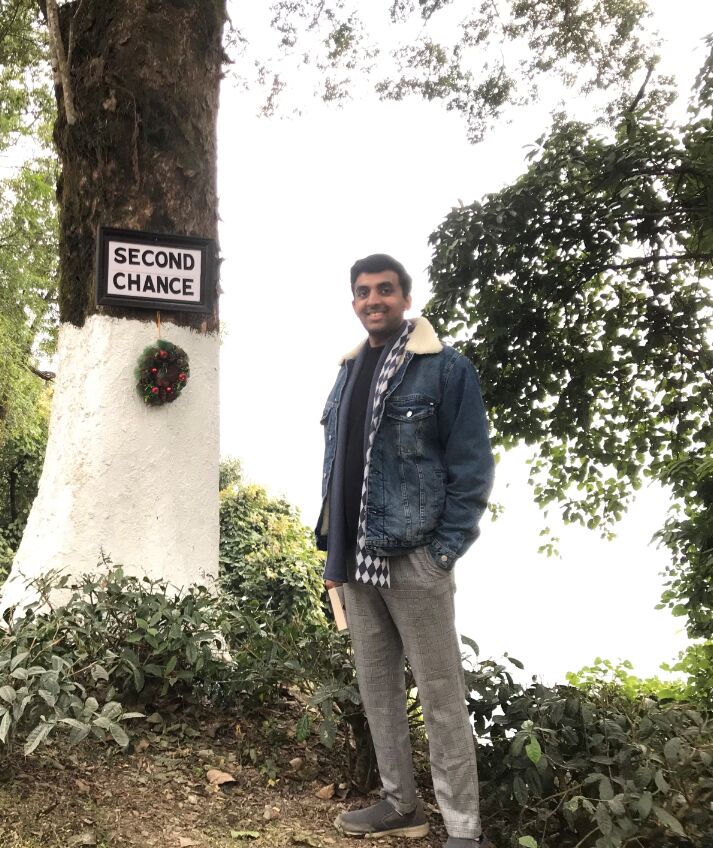

The Selim Hill Collective is based out of their Second Chance House at the garden, which offers space and opportunity for photographers, filmmakers, journalists, researchers, writers, wildlife enthusiasts and students to work with them. But these initiatives are in their infancy. The objective is to first revive the tea garden and make it commercially viable. The road ahead is long, but any attempt at reimagining a business and a space which has existed for decades will take time.

(You can visit the Dorje Teas website here and follow them on their Instagram page.)

(Edited by Divya Sethu)

No comments:

Post a Comment