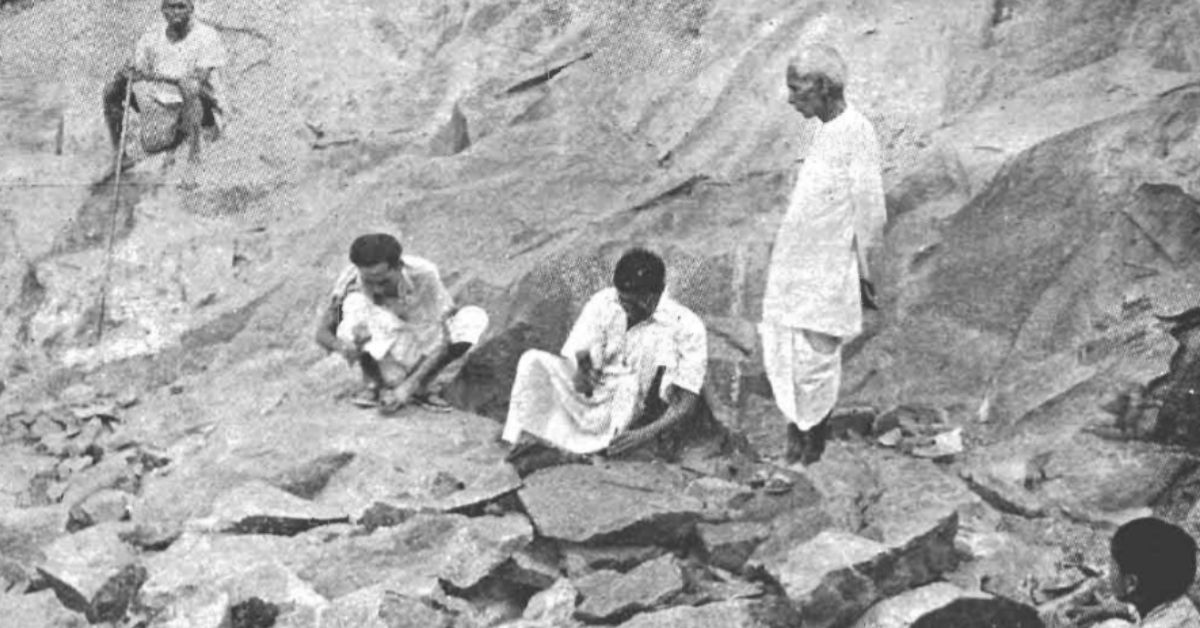

Located on the bank of the Phalgu River, the Vishnupada temple in Bihar’s Gaya district is surrounded by rocks and water. The marvellous structure, which dates back to the 8th century, has put Patharkatti village on the map of the finest stone carvings.

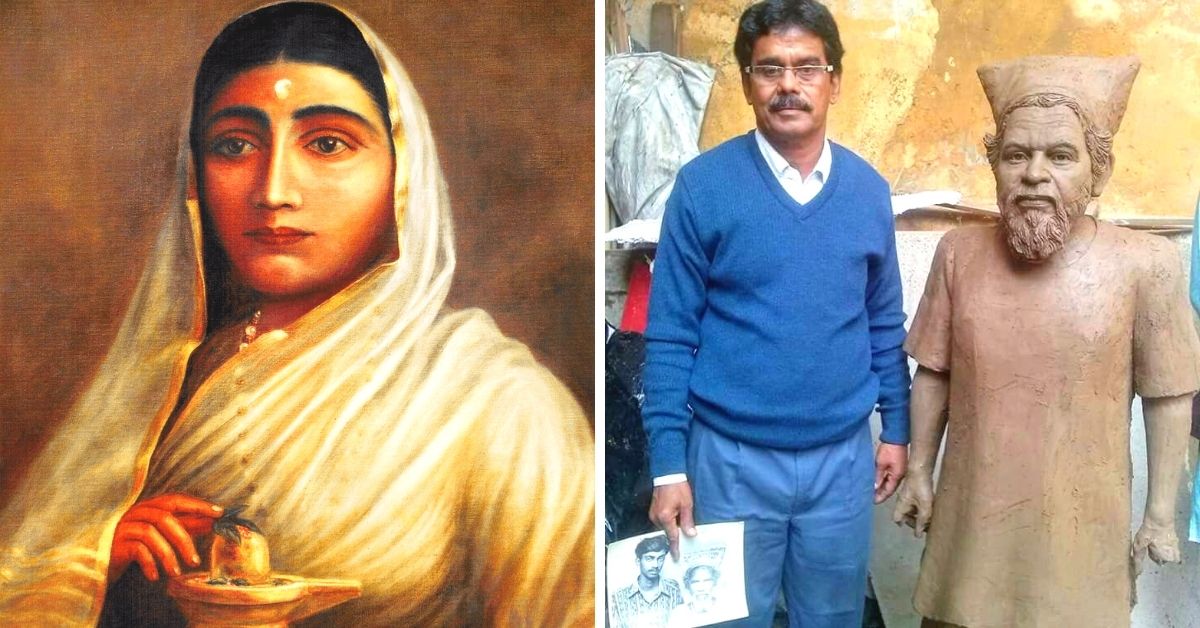

The temple was built by Queen Ahilyabai Holkar. According to folklore, she was searching for craftsmen to erect the temple with stones that could survive harsh weather conditions. Unable to source skilled men locally, she procured them from Rajasthan’s Gour community. On the completion of the structure, when the workers wanted to return home, the Maharaja of Tekari allotted them a piece of land in Patharkatti village, 40 kilometres away from Gaya. Since the area fell under the Maharaja’s jurisdiction, the artisans were allowed to quarry the stone for free initially, and later at an annual royalty of Rs 1.50.

While Ahilyabai only played a small role in the migration process, she ended up generating livelihood for several families, as well as enriching a tiny village with art and craft. Devotees and buyers from across both India and the world visit the village to purchase authentic sculptures of gods and goddesses, as well as decor and household items such as bowls and thalis made from black stone.

However, there are other historical accounts that state that the stone carvings were present way before the Maharani became involved. Ashok Sinha, director of Upendra Maharathi Shilp Anusandhan Sansthan (UMSAS), a government-run organisation that looks after art preservation, confirms the same.

“We have found several sculptures made from black stone across Bihar, especially in the Nalanda district, which are much older than the Vishnupada temple. Such stones are only found in Patharkatti village, and some settlements were living in the area before communities from Rajasthan came in,” Sinha tells The Better India.

Sinha also hints towards the other possibility, according to which Ahilyabai revived the dying craft after several decades by constructing a temple. This does not come as a surprise to him, given that stone crafting in Patharkatti has been revived multiple times throughout various periods. The most recent attempt was made in the 1960s by UMSAS.

“It is quite amusing to see how this craft keeps coming back to offer the world such exotic items,” says Rabindra Nath Gour, who is an eighth or ninth generation craftsman. “Our ancestors from Jaipur were employed by the Maharani for the temple work in 1787. Since then, we have been living in Patharkatti and passing down the skills from one generation to another.”

So what makes Patharkatti (named after pathar or stone) village and its carving techniques stand out from the rest of India? Rabindra and Sinha provide insight into its history, culture and economics.

Eternal patharkatti stoneware articles

It was only a few years ago, when Rabindra visited an exhibition on Odisha, did he realise the pricelessness of a hookah made from black stone, that had been dumped among other non-useful items in a storage room. Alongside the hookah lay kharal (oblong boat-shaped vessel), plates, and glasses covered in dust.

“During the exhibition, I saw that the items displayed were being guarded with tight security. I learnt that these century-old items had been kept as treasures. I knew the stoneware articles in my house were 200 years old. UMSAS was pleasantly surprised to see them. What struck all of us the most was the sturdiness of the raw materials. There is no crack or any kind of damage even after four centuries,” says Rabindra.

Sinha, who has been actively providing training to artisans on stone crafting, says items made from patharkatti stone can last for centuries if kept in a protected environment. “The endurance of patharkatti stone is the reason why the village is well-known for its artefacts. The beauty is that an artisan can procure raw materials at low rates and sell the finished item at profitable rates.”

Typically, the items are divided into three categories – utilitarian, ritual, and decorative-cum-ritual. The utilitarian items include bowls, plates, pounding vessels and pestles. Kharal, for example, is used by local medical practitioners and chemists to prepare medicines. Homemakers use it to make masalas. Villagers even prepare a famous local non-alcoholic drink by grinding hemp with green leaves and water in the kharal. Other bowls are used to store oil, paste and other such liquid, which ensures a long shelf life. Meanwhile, the ritual items are majorly stone statues of deities.

“We used different types of stones such as Pirkasauti, Parajit, Tamra, Hansraj, and Motia. For decorative materials, Dhanmahua stone is used as it can give intricate touches. The best part is that one need not colour the product black. It will automatically turn black once oil and wax is rubbed on it. Depending on the object and raw materials used, it can take anywhere between a day to six months to prepare the product. Hammers and chisels are the main tools used to make the product. A majority of the artisans have a dedicated space in the house where they prepare and sell the items,” says Suresh Lal, a sixth-generation craftsman from Patharkatti.

Most artisans learn the art form while in school. Rabindra was around five when he made his first item (a diya) from granite stone. By the time he was a teenager, he was selling small items for 10 paise, “I still remember the joy of receiving brass coins which gradually turned into crisp notes. On average, the monthly income of an artisan is Rs 15,000. It fluctuates as per the demand. During the COVID-19 lockdown, the entire village struggled to source raw materials and orders so we were forced to reduce the prices.” Rabindra’s high-end products cost up to Rs 10,00,000.

However, not every artisan has strong market linkages like Rabindra. The villagers are often duped by middlemen with dirt-cheap rates and because the artisans have to feed several mouths, they compromise, says Rabindra.

On various occasions, UMSAS intervenes and helps artisans sell their items in exhibitions across India. But mostly, the artisans have to rely on their marketing calibre. This has led to the younger generations opting for other professions.

“The craft in Patharkatti has gone through many turbulent times. Even now, we are suffering because of the pandemic. But the craftsmanship and skills of the artisans have helped us pull through and overcome difficult times. I really hope the training by UMSAS encourages more villagers to take up stone carving to ensure it stays eternal,” says Rabindra.

Edited by Divya Sethu

No comments:

Post a Comment