In May last year, the New York Times published a report on June Almeida, a Scottish virologist, who, in 1967, used “a powerful electron microscope to capture an image of a mysterious pathogen — the first coronavirus known to cause human disease”. In the Common Cold Research Unit in Salisbury, England, British virologist David Tyrrell and Malcol Bynoe had been isolating a new class of viruses from organ cultures, and Almeida, who was working in Tyrrell’s lab, produced the first image of the virus.

Around the same time, Dr Dorothy Hamre, a virologist and infectious disease researcher at the University of Chicago’s Department of Medicine, was the first to isolate a strain of a virus from samples she had collected from the students at the school. This strain was named 229E, and the findings were published in this paper.

In 1975, the virus was christened when a group of scientists, including Tyrell and Almeida, made a proposal to “group together a number of recently recognised viruses under the head of coronaviruses”. However, Hamre’s name remained missing from this paper.

Over 50 years later, this caught the eye of Professor Padmanabhan Balaram, a biochemist and former director of the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Bengaluru.

Amid a pandemic caused by the same virus that has gone on to become a defining moment of the 21st century, Prof Balaram began his hunt to ascertain the identity of Dorothy Hamre, who was the first to discover a strain of the coronavirus.

How do you find an invisible person?

In 2020, just as Prime Minister Narendra Modi made the announcement for the first nationwide lockdown, Prof Balaram, who presently holds a Chaired Professorship at the National Center for Biological Sciences (NCBS), was looking for better ways to conduct his classes online. He wanted to use this time to discuss with his students topics they’d not find in their textbooks. Intrigued by the virus that had only just begun to wreak havoc on the world, he decided this was going to be the topic of discussion with his students.

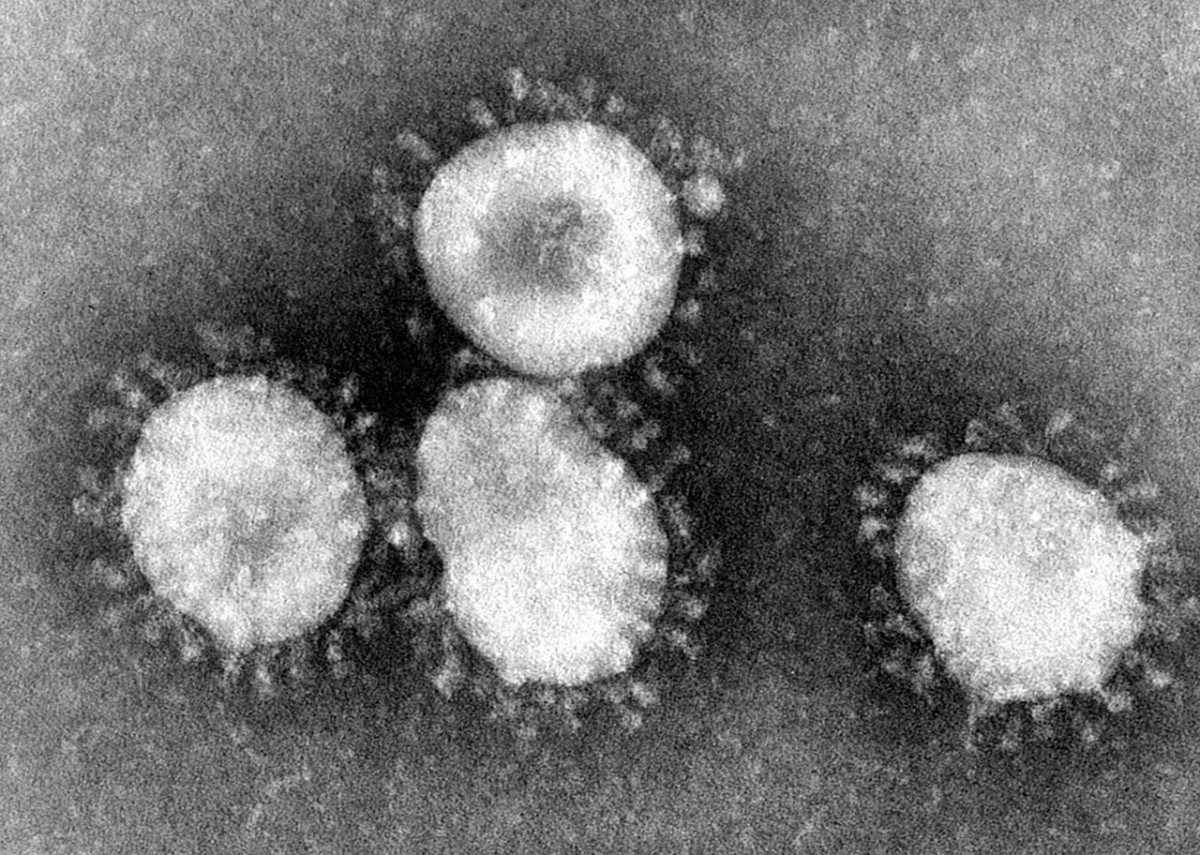

“Whenever I discuss something with my students using PowerPoint, I always like to put a picture and a brief history of whatever we’re talking about,” Prof Balaram told IAW2020 Milli Sessions. “So while discussing the coronavirus, I wanted to put a picture of the electron micrograph of the coronavirus. I went back to the literature around the virus, and read in the National Geographic that the first electron micrograph was taken by Almeida and Tyrrell. When I read the paper they’d written, I found among the references the mention of one Dorothy Hamre and an acknowledgement to her that said that she provided the virus sample from which the electron micrograph was taken.”

Prof Balaram thought Hamre must be a famous virologist, so he began looking for a picture of hers that he could add to his presentation. But his search came up short. “I spent about half a day looking for her photo and found nothing. That’s when I realised she might be an invisible person,” he said.

During the lockdown, Prof Balaram would end up speaking every day with his son, who is doing a PhD in South Carolina. When he told him about his recent discovery, the young man did a Google search to find out more. They found many scientific publications with a good number of Google scholar citations, but no picture of Hamre. Their search took them to the archives of the Northern Arizona University’s library. Under the ‘Alexander Brownlee Collection’, they found what they had been looking for.

As it turned out, Alexander Brownlee was the husband of Dorothy Hamre. The duo found a small biography that stated she had been trained in bacteriology and biology, and had done her PhD in Colorado. However, barring a few, most photographs in the archives were of beautiful landscapes in southwest America. “Every few pictures, we’d find small figures in the photos, but they didn’t look like a biologist who had discovered the coronavirus,” Prof Balaram told Milli. “So I wrote to the archives and told them what I was looking for. The head of the archives put me in touch with Sam Meier, an archivist.”

Sam Meier and her colleague Kelly Phillips began combing through the finding aid, which indicated the presence of several portraits of Hamre and her husband. The two began thinking of ways they could digitise these photos without constant access to the required equipment during the lockdown. While doing so, they also found that Hamre and her husband had retired to Colorado in the late 60s and the photographs they had found so far encapsulated the time the couple spent engaging in activities such as river rafting, jeep rides, hiking and other outdoor activities.

Prof Balaram’s search had led him to the conclusion that Hamre was possibly an extremely senior figure. With Sam and Kelly’s help, he was able to trace the year of her birth, 1915, and the date she passed — 19 April 1989.

‘Many threads left to unravel’

“Her publications begin in 1941, and the work around coronavirus was done around the 60s, which meant that she had a long scientific career before that,” Prof Balaram noted. “When she came to Colorado, she began work on the rhinovirus, which causes the common cold. That’s how she discovered the coronavirus as well. I would put her as the co-discoverer of coronavirus alongside Tyrrell. Dr Hamre had even written a monograph on the rhinovirus. In virology and even in the context of today’s pandemic, it’s important to recognise that the coronavirus was discovered when scientists were trying to look for infectious agents that caused the common cold.”

Prof Balaram adds that Hamre had been looking for students at the University of Chicago who came to the infirmary with a cold or sore throat. “In biology, the coronavirus was not considered as important because it was not causing a major problem to humans. So even when Tyrrell wrote one of his last papers, the coronavirus was only causing mild infections. It’s only later that the variants of this virus started causing more severe infections like SARS, MERS, and the current pandemic,” he explains.

The discoverers of the coronavirus have been listed as Juen Almeida, David Tyrrell and “others”, but Prof Balaram believes it should be the other way around. “It should be Dr Dorothy Hamre, David Tyrrell, and June Almeida,” he opined. “It’s the 229E sample that gave the image of coronavirus, where you see the spikes, which are the ‘corona’ that give the virus its name.”

Last year, Prof Balaram published his findings for The Frontline, where he wrote, “…As a woman building a scientific career in the days of the Great Depression and the Second World War, she must have been gifted with both imagination and resilience. She must have honed her experimental skills in the hard crucible of infectious disease laboratories. As the coronavirus rampages across continents, Dorothy Hamre emerges as a distant and anonymous presence.”

“Shortly after I wrote the first article, a young man working for the Yale Literary Review contacted me to find out more about Hamre,” Prof Balaram tells The Better India. “I think we have to continue looking for more details surrounding an interesting figure such as herself. That she was a woman scientist who obtained a PhD quite early on and then worked as a scientist even before the Second World War is certainly quite commendable, as this was not a good time for women to pursue science in America. She appears to have moved around a bit, but stayed quite long at each place she worked in. She was very well regarded for her work at Squibb Institute of Medical Research in New Jersey. In fact, one of the earliest antivirals was developed with her contributions.”

He adds, “She then moved to Chicago, where I found that she was a research associate until her demise. Her husband, meanwhile, is a controversial figure. He was in the field of statistics, who once testified in Supreme Court hearings in the 1960s on whether tobacco causes cancer or not — he did so on the behalf of the tobacco lobby. I believe there are many more such interesting threads to her story that need to be unravelled.”

All resources, reading material and videos provided by Professor Padmanabhan Balaram.

Edited by Yoshita Rao

No comments:

Post a Comment