How did a 20-something girl, often described as a cinema actress, come to India to escape taunts by her mother to get married and take part in combat as a ‘Naga Queen’?

This was my question to Catriona Child, daughter of Ursula Graham Bower, who very graciously speaks of her mother’s exploits with the Zeme Nagas during the Japanese invasion of British-ruled Indian territories.

The ‘society beauty’ traded cocktail parties for khakis and joined around 150 Naga hillmen with ancient muzzle-loading guns, battling over 800 square miles of mountainous jungles.

It is said that she came to colonial-ruled India in 1937 as a tourist to “putter about with a few cameras and do a bit of medical work, maybe write a book”. But the reality of it was quite grave.

“When I was very young, my mother wrote a book called ‘Naga Path’ and gave many lectures on the radio. Only later, after I read her book, did I begin to understand what she had done,” says Delhi-based Catriona, a communications expert and writer.

She adds that Ursula’s book is written in a comedic way, as her mother had quite the sense of humour. But it was only after a few Nagas visited them in the UK that Catriona realised her mother’s role in the Japanese invasion.

The story began in the 1930s when the financial crisis in Britain at that time left Ursula’s family with limited means. She was preparing to go to Oxford University, but her family told her that there wasn’t enough money to send both her and her brother to University.

“She was very bitter about this because she loved to study, and she would’ve liked to learn Anthropology probably. But now she was being handed the chance to learn about other cultures in the field,” Catriona says.

“One day (in Northeast India), she got the chance to go touring with the civil servant and his wife. They went off into the jungle, as he was taking medicines to villages that lacked facilities. People would get injured as they would cut themselves with an axe or get clawed by a bear. These wounds would get terribly infected because of the tropical climate. There were no antibiotics. The doctors had something called sulpha drugs,” Catriona tells The Better India.

And thus began Ursula’s encounters with the Nagas and their rich traditions and heritage. Twelve years after her first encounter with the Nagas, Ursula, in her book, writes:

“Bead necklaces drooped on their bare, brown chests, black kilts with three lines of (4) cowries wrapped their hips, plaids edged with vivid colours hung on their coppery shoulders. Tall, solid, muscular, Mongolian, they stood, a little startled, as we shot by.”

Her writings of the daily Imphal Bazaar are so descriptive that one thinks they’re reading poetry:

“There was a tingling smell of smoke, spices, dust and marigolds in the air, there were lorries nosing and honking through the press, there were half-naked hillmen stopping to stare, and away and beyond it all was a bronze-green twilight and hills of black velvet against a shot-silk sky.”

Initially, she took photos of the locals and their crafts and customs and showed them to those back in London – who were impressed by these “never-before-seen photos of tribes”. Then, in 1938, Ursula came back to India and the following year, Britain entered World War II, which had already been raging between Japan and China for years now.

Catriona recalls that her mother saved up her allowance money and booked another passage to India in 1939. But this time, she was told by the officials that she couldn’t go back to the hills, which upset her.

“She went to see one Mr Mills, advisor to the governor in tribal affairs. At the time, the Zeme Nagas, who dwell in Manipur, Nagaland and Assam, had rebelled against the British. The army intervened, and the rebellion was shut down, but Ursula wanted to know why it had all happened,” Catriona narrates, adding, “Mills thought that a woman might be more approachable to the tribes. So she was sent to Laisong village where she would stay and study.”

But when she arrived, she realised the purpose of their rebellion was to form a new religion led by a goddess.

Return of the ‘Goddess’

Catriona says, “There were some very stupid policies by the British which had left the Zemes very poor and without food. They had been starving, unnecessarily so. This is why the new religion started.”

The teenage leader of the rebellion, Rani Gaidinliu, had been put in prison by the British in 1932. “But before she was imprisoned, Gaidinliu said to her followers — don’t worry, they’re only putting one avatar of mine in prison. I will return to you in a slightly different form. So, when my mother arrived, half the people worshipped her as some reincarnation of Gaidinliu. Some of the villagers would throw themselves down at her feet and bring her presents. But the other half, who had not been followers of Gaidinliu or didn’t believe that she was her avatar, would not talk to her.”

Ursula would still go to every village to treat people for their headaches and sores. Gradually, they came to accept her.

By 1942, the Japanese were rapidly advancing in Burma. “Masses of Europeans were streaming out of Burma. The Burma border not being far away, they [Ursula and the Zemes] heard of the many people who died on the way. So my mother was roped in with a couple of Zeme helpers like Namkia [her interpreter] to run a tea stall at Lumding station (in present-day Assam) for the refugees coming through,” Catriona says.

But she was always afraid that she would be told to leave by the British. “European women were not allowed in these areas unless they were touring with their husbands.”

She adds, “At the time, the Japanese were advancing, but no one was quite sure when they would attack India. The mountains between India and Burma were impenetrable, and no one was sure which route they would take to reach a railway to get to Delhi.”

“There was a pass coming through Manipur, which the Japanese could have used. The Army Headquarters needed an Intelligence Unit to check for Japanese invasion through this route. So my mother was recruited and asked to recruit 150 local scouts, who would patrol the paths,” Catriona says. This made Ursula part of the famous British ‘V Force’, which operated across 800 miles of India’s Eastern frontier from 1942 to 1944.

At one point, the Japanese got very close. While these scouts were meant to be patrolling and not fighting, they were unarmed. Ursula urged the British to give them back their guns taken away after their rebellion led by Gaidinliu. Many Nagas were recruited to fight in the First World War as labour corps and were given ancient muzzle-loading guns.

When the enemy was near, Ursula sent a telegram to the Army Headquarters saying she would take her scouts to look for them. The Headquarters decided to support her and sent her a few more rifles. She was given the rank of ‘Acting Captain’ though she was registered as a typist on the books.

She was the only woman to hold a de facto combat command in the British Army during WWII.

“Then there was the battle of Kohima (April to June in 1944) and the action went away from her area. But their main work was dealing with people coming through from Burma, who were deserters from the army and were looting the villages. They also looked for aeroplanes in the jungle and looked for lost aircrew,” Catriona says.

The Zemes had enormous respect for Ursula, as some of the village headmen asked her to stay on when they realised that the British were leaving. “They finally had someone from the British that they trusted,” Catriona, who visits Laisong every chance she gets, says.

Even today, Catriona is received with a tremendous welcome. “These welcomes are because of her. The first time I went there, there was a party. Another village in Manipur picked me up in a chair and carried me into the village. They presented me with a mitten from the wool of the semi-wild bison. They also gave me beautiful gifts of their wrap-around skirts, shawls and beads.”

A Garden Proposal

British society, at that time, was very much like Indian society, says Catriona. “Girls were not supposed to get jobs and were supposed to learn nice manners, social skills and get married. My grandmother would have hoped that when my mother came to India—as did a lot of British women who came to India to meet lonely bachelors working for the government—she would find a husband. But my mother had no such idea.”

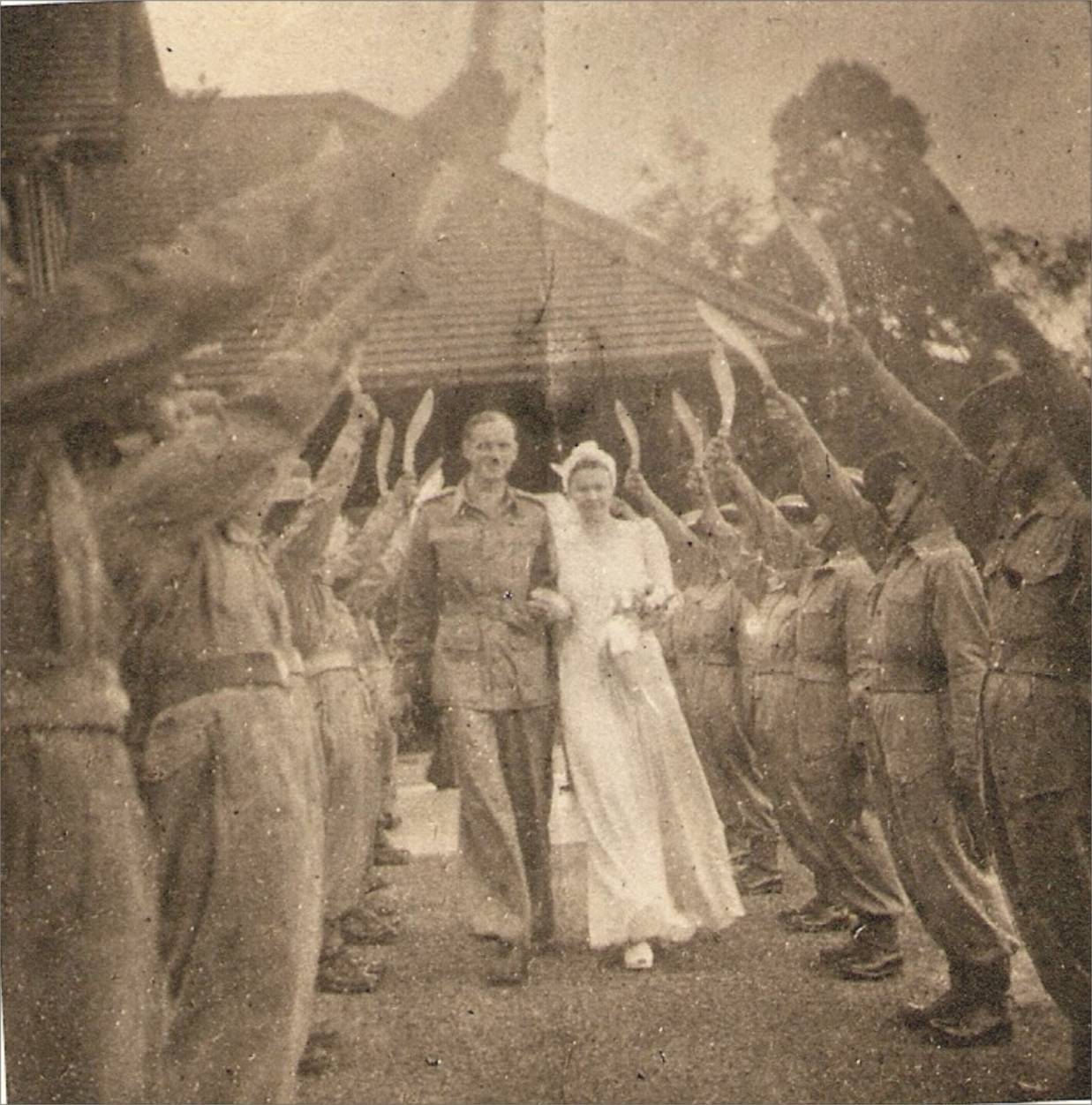

Ursula wed Lt. Col. Frederick Nicholson Betts in 1945 in Shillong. “That’s an awful mouthful,” Catriona laughs, “My father was mostly known as Tim. He had heard about my mother because she had quite the reputation. He was in the same intelligence force. He was 39, and his family was also waiting for him to get married. But he liked adventure and jungles and couldn’t find any women who shared his enthusiasm.”

She continues, “There was a time he became very ill from fighting in the war. He had walked through the jungle for three weeks and became very sick. And while he was recovering in hospital, he heard about my mum and her exploits. So he thought — she sounds like the right girl. (chuckles).”

Tim was very interested in butterflies and wrote to Ursula asking if he could visit her village on his holiday and collect butterflies. “This was just an excuse. But my mother was a bit irritated, as she didn’t want visitors at the time and wanted to get back to her academics. He kept coming back, not keen on catching butterflies. Finally, he came back and took her out to the garden one day and proposed to her. To her surprise, she said yes, and they ended up being married in three weeks.”

Though she was referred to as the ‘Naga Queen’, Catriona says her mother disliked the title. Yet, playwright Chris Eldon Lee read her mother’s diaries and converted the story into a one-woman play titled Ursula: Queen of the Jungle. The play also went on to showcase at the Edinburgh Festival in 2017.

Having grown up reading her mother’s book and listening to so many stories, Catriona first visited Nagaland in 2000.

“I looked at some of my videos and compared it with hers and saw that the techniques that they used for taking out the seeds from the cotton were the same,” she says.

Carrying her mother’s legacy forward, she did a water project. She put in piping to help a community in Laisong that was adversely affected due to the droughts — some of whom died due to cholera. In addition, Catriona led a pickling project in another village to enable locals to earn from sources other than agriculture.

Catriona’s family also built a guest house and library and supported a couple of schools in the region.

Now, married to a Kashmiri and a citizen of Delhi since 2005, Catriona brought the play to Laisong, where it all started. “The villagers were confused as they were not used to live theatre. Moreover, one actress did all the parts, and most of the jokes were lost in translation. But what brought them joy was to see their grandparents in the photographs taken by my mother projected on the backdrop,” she signs off.

(Edited by Vinayak Hegde)

No comments:

Post a Comment