Respected Auntyji,

I have been married two years and we have a one-year-old daughter. My husband is an MA. I started working in a factory when I was fifteen. He came to our village for marriage. On the first night of our wedding, he asked me if I had boy friends. Foolishly and honestly, I told him I used to be very fond of an Indian bloke who worked in the same factory, but I’m happy to be married to him. Since then, he accuses me for no apparent reason. He started calling me a prostitute and says…I go out with English men, Jamaicans and Pakis…I can tell you honestly Aunty ji, I have never in my life gone out with any man. Why is he torturing me so much? He is threatening to take away my baby to India because he says, “I don’t want my daughter to become a prostitute under your filthy influence.”

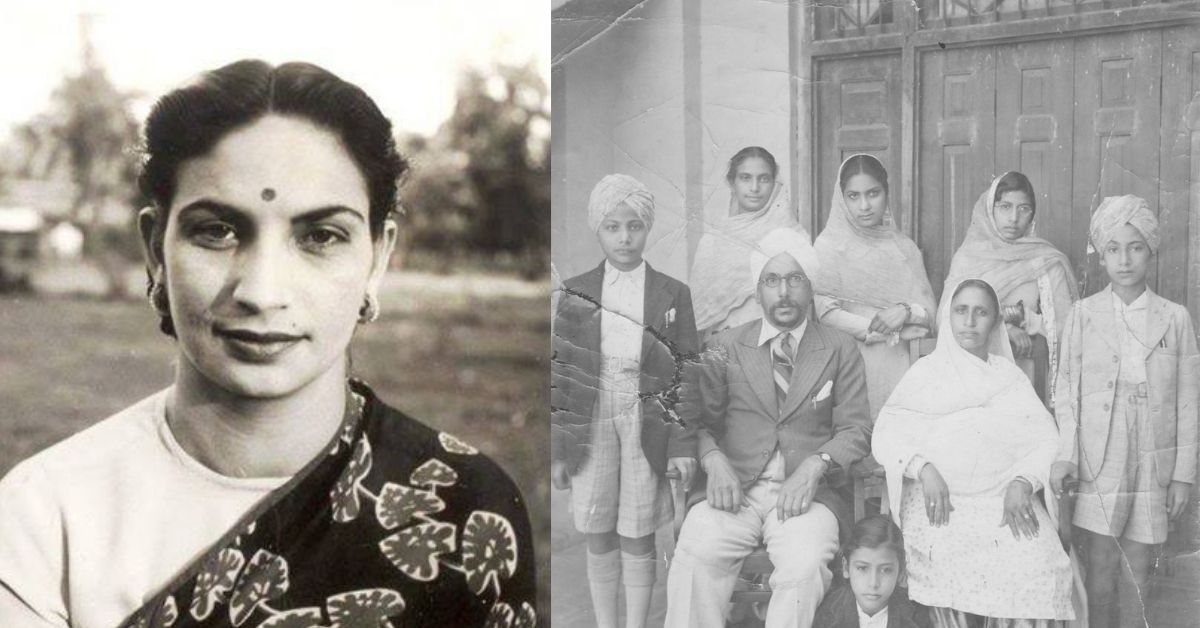

This message is one of several from the postbag of Kailash Puri, often called ‘Humraaz Maasi’ (confidante aunt). A woman of many talents, she was an ‘agony aunt’, author, broadcaster, poet, counsellor and a self-proclaimed sexologist, who, through the 60s and beyond, became a shoulder to cry on for several Punjabi women and families settled across India, Canada, parts of the US, Germany, and other European countries.

Towards the late 20th century, Kailash became a rare challenger of patriarchy and the conservative Indian community with her openness and willingness to discuss ‘taboo’ topics. From domestic violence to impotence, adultery, alcoholism, dowry, and more, women (and sometimes, men), approached Kailash for several issues, to which she always lent a sympathetic ear.

But before she became a sexologist, she was a demure and naive young immigrant, who, towards the end of World War II, hopped off of a troopship from Bombay to Southampton in England to come live with her husband in a foreign land. She was all but 18 then.

Becoming ‘Humraaz Maasi’

Kailash was born in 1925 in a village near Rawalpindi, Punjab in undivided India. In her book Pool of Life (2013), she recalls her first brush with the customs surrounding marriages and new brides. “From my earliest childhood, I overheard my elders speaking of some new bride:

What a wonderful daughter-in-law. She worships her parents-in-law. Saara din kam lagi rahindi hai. Boldi nahi (She works away all day without speaking).”

Kailash went on to note, “A bride’s first priority was to please her mother-in-law. Only then would she be accepted into her husband’s family. If a girl was a good daughter-in-law, then…there would be domestic peace.” As she grew older, she became more accustomed to the idea that one day, she too would be “bundled up in scarlet and gold and given away in marriage”. She adds that nobody considered a girl worthy of much else and there was no emphasis on aspects such as compatibility, happiness or a healthy sexual relationship between the couple. “Sex had always been a taboo, a dirty aspect of life which must never be mentioned,” she wrote.

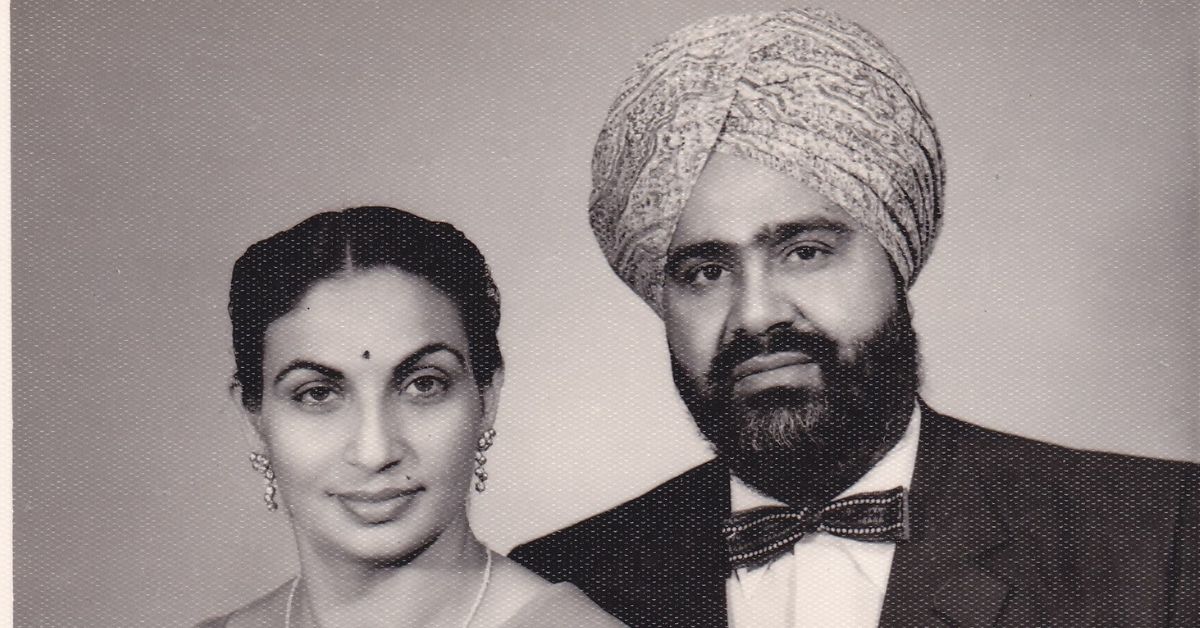

As Kailash turned 16, she met and fell in love with Gopal Singh Puri, a young scientist who she recalled was “much sought after as a son-in-law”. “It was an unusual type of marriage in those days,” Shamindar Puri, Kailash’s eldest son, recalls to The Better India. “My father had seen her at a family wedding and told his mother that he would like to marry her. My parents met up and there was a big scandal, which was considered inappropriate back then. My father’s second cousin wanted his own sister to marry him, so that uncle created a little hue and cry about the whole ordeal. But my father was persistent, and knew who he wanted to be with.”

Two years after their marriage, Gopal received a Research Fellowship through the Government of India in Plant Ecology for a second doctorate at University College, London. He went there first to make sure he had enough money to sustain his family, and Kailash followed via boat some time later. “For a young girl from Punjab to travel all by herself to a cold, foreign land was certainly traumatic, but she handled it well,” Puri adds.

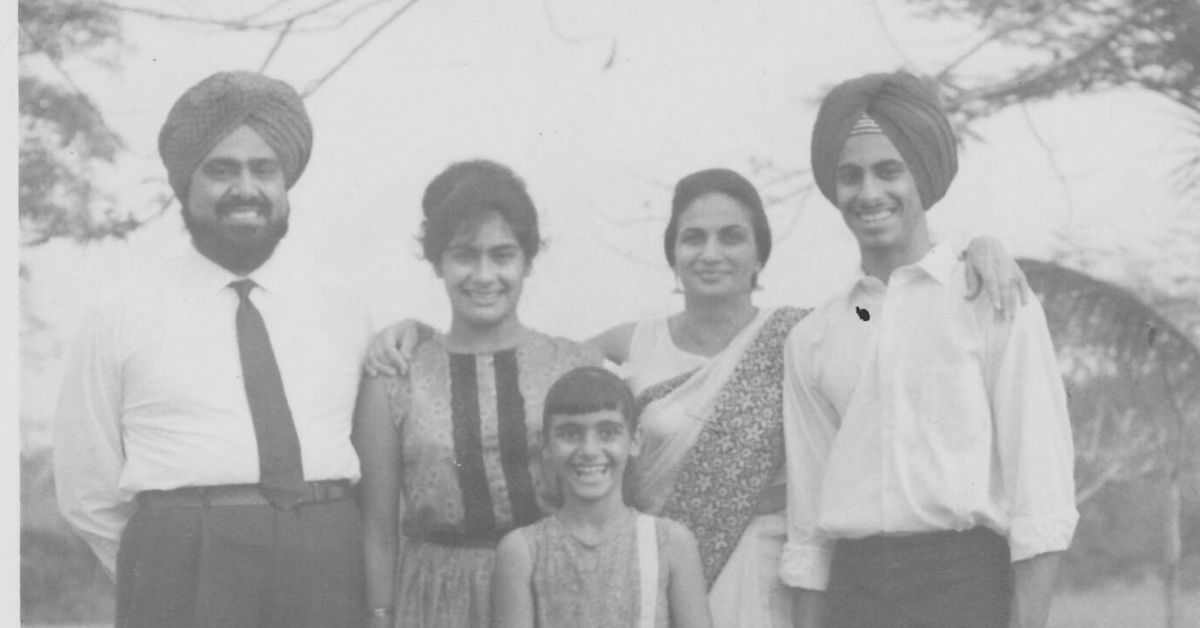

The couple rented out a small flat not far from the university. As Kailash slowly began to familiarise herself with a world so different from what she was used to, her perspectives changed. “My mother never got to complete her education, so she slowly learned English,” says Puri, who was born in 1947. He adds. “At the time, there was a food shortage, and the landlady would often give my mother her own food vouchers so we would have enough food. Things were hard but my parents made a good life for themselves.”

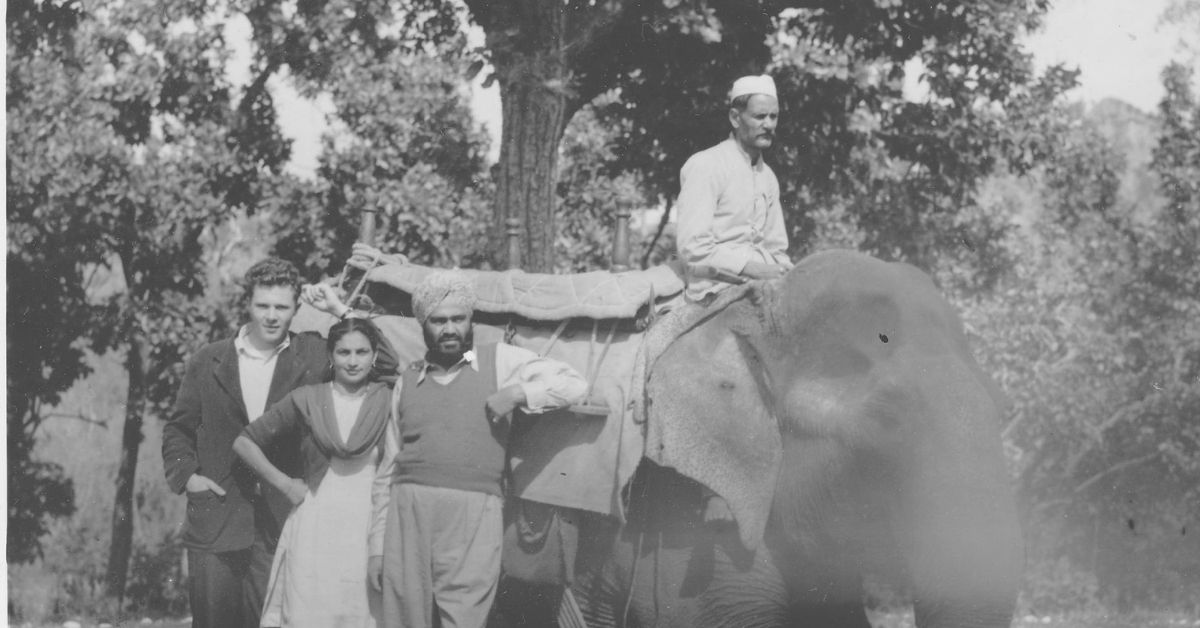

Shortly after Partition, the family returned to India, where Gopal was appointed as an ecologist in the Indian Forest Research Survey in Dehradun. The family lived amid the vast campus in the midst of tall hills, where Kailash spent her time baking cakes for parties, interacting at various social events and learning instruments such as the sitar.

It was at Gopal’s prompting that Kailash took up writing, Puri says. After she won a few cookery contests, she began writing features on cooking and sent them to Punjabi magazines. She received a response from the editor of one such magazine, who wanted her to write three pages a week on whatever she may like. And so Kailash began writing on cookery, women, marital relationships, interior decor and gardening. When women readers would send in letters about their marital problems or issues such as backaches and menopause, the editor would pass them on to Kailash.

This gave her the idea to start a Punjabi literary magazine of her own. Gopal wholeheartedly supported the idea. So, in 1956, she launched Subhagvati, which covered domestic matters, entailed various recipes, spoke about familial relationships, children, current affairs, and contained short stories and poems.

Subhagvati was the first Punjabi magazine to exclusively cater to women and their needs.

When the Government of India began focussing on birth control, Subhagvati wrote in favour of it, which invited severe criticism for Kailash, who was told she was “ruining family life” and “prejudicing our daughters-in-law”.

Lessons from Kamasutra

Kailash’s work found critics in leaders of religious communities, as well as men with wounded pride and mothers-in-law who saw their daughters-in-law deviating from what was expected of them. Moreover, her work was often mistaken as pornography, but she emphasised that her work and understanding of sex came from the Kamasutra, and that porn reduced women to an inferior status.

Puri notes, “My mother wanted to help people, particularly women. In those times, no English person really knew the kind of lives that Indians or Asians were leading. So her work helped highlight that. The more she wrote, the more she realised that other than marital problems, there were many sex-related issues that couples were going through. Those became hard to address in a society that wanted to keep such issues quiet. So she certainly invited a lot of criticism.”

After a stint in Nigeria, the family returned to England in 1966, where Kailash began teaching oral Punjabi to the police force and other professionals whose work required it. She also gave cookery classes, and was appointed by Marks & Spencer as a consultant on Indian cuisine and was among the first few south Asians to publish texts on Indian cooking, much before stalwarts such as Madhur Jaffrey took over.

Owing to the limited sex vocabulary that Punjabi language contained, she also coined new terms such as madan chhatri (cupid’s umbrella) for the clitoris, and pashm (silk) for pubic hair.

“Today, the world has changed slightly, and my mother was among the drivers of these changes. She gave a lot of people the confidence to speak about things that weren’t spoken before,” Puri says. “As a result of her work, I believe Asian women were empowered to be a bit more outgoing. She always lay great emphasis on being true to your roots without letting them inhibit you.”

Kailash won several awards and accolades for her work, including the Woman of Achievement Award in 1999, the position of the Ambassador of Peace in 2000, Woman of the Year in 1984, and the Lifetime Achievement Award (Ealing) in 2004. She was also the Chairperson of the Community Relations Council in the UK from 1968-75, an executive member of the Women’s League for Peace and Freedom from 1970-90, and the President of the UK Women’s Asian Conference from 1980-95.

Kailash began her journey as a young girl with little education and ended up with over a long list of accomplishments for her work in journalism and in promoting Punjabi. She was also recognised by Indira Gandhi and Margaret Thatcher for her work. She was one of the earliest examples of what changes can take place if a woman decides to speak up.

“One of the fondest memories I have of my mother is shortly after my father’s death, when we travelled to Goa. My mother came onto the beach with all of us and decided to play cricket with her grandchildren. It was a sight to behold. I don’t think I’d ever seen an elderly Asian lady play cricket on the beach in non-traditional clothing. I snapped a photo of that moment, and it remains one of my favourite photos. That’s the kind of woman she was — she had no inhibitions, and was always ready to take up new challenges,” Puri concludes.

Edited by Yoshita Rao

No comments:

Post a Comment