What started as retaliation to Lord Curzon’s infamous Bengal division in 1905 turned into a full-blown Swadeshi movement, giving rise to iconic brands including Asian Paints, Tata and Steel, Lakme Cosmetics and more. These brands not only crippled the sale of foreign goods, but also epitomised unity and independence.

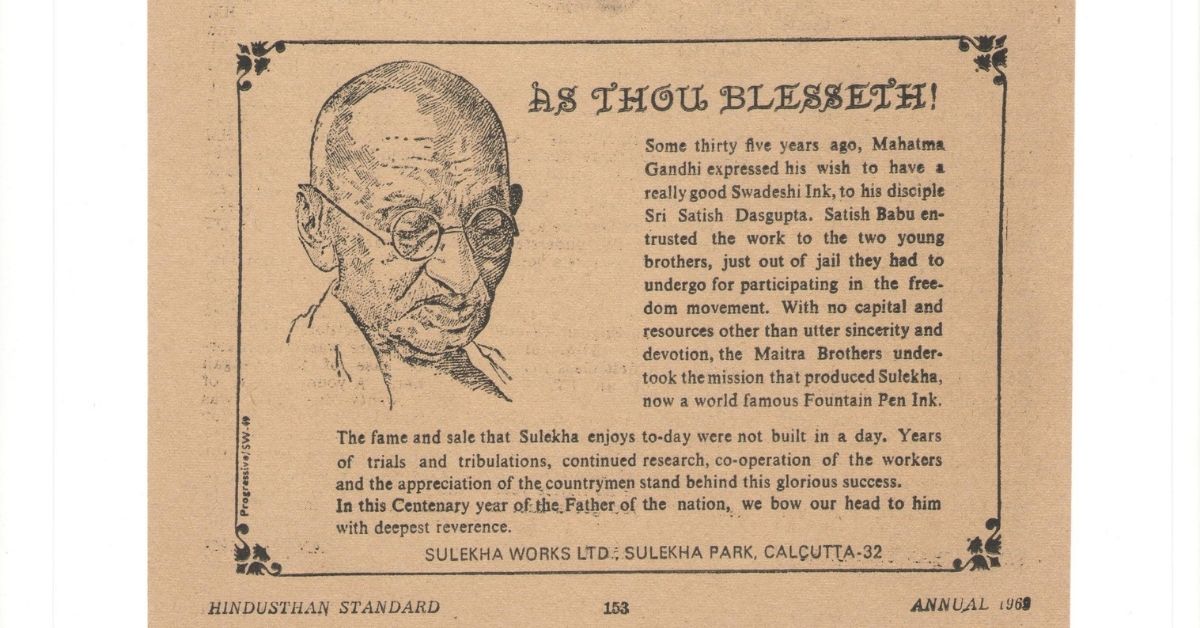

During the 1930s, when the Swadeshi (Swa – ‘own’ and deshi – ‘country’) movement was at its peak, its founder Mahatma Gandhi was ferociously looking for a locally-made ink to write letters and petitions. He shared this with Satish Chandra Das Gupta, a freedom fighter from West Bengal. Credited with making Krishnadhara, India’s first Swadeshi ink, Gupta shared his formulation with the Maitra brothers, Nanigopal and Sankaracharya.

The brothers, who lived in Rajshahi (now in Bangladesh), had just been released from jail and jumped on the opportunity to defy the British again. They later met Gandhi at a public rally and took his blessings.

The deep-rooted nationalism was such that Nanigopal even left his teaching job at the Rajshahi University, as he was ordered to switch from dhoti (a traditional attire) to a suit. So he moved to Calcutta (now Kolkata) and started selling the ink. The sales increased multifold and it came to be known as Professor Maitra’s ink.

The name Sulekha (Su – good and lekha – writing) came about only when shopkeepers asked what the ink was called. The name was supposedly given by India’s cultural ambassador, Rabindranath Tagore. While the company has no proof of this, the Maitra family has chosen to go with this version of the story.

In no time, the fledgling pen makers became a household name, as stalwarts including Gandhi, former prime minister Morarji Desai, former West Bengal chief minister Dr Bidhan Chadra Roy, and legendary filmmaker Satyajit Ray wrote with pens infused with Sulekha’s ink. In fact, the ink and its bottle made cameos in Ray’s Feluda stories and movies as well.

The company grew exponentially over the next four decades. Between 1970-1980, it was at its zenith, with monthly sales worth one million bottles. Ask any Bangali about Sulekha and you will see a sense of nostalgia engulf them.

So it came as a blow to many when the company shut in 1989. While Sulekha returned in 2006 with another line of homecare and solar-powered products, it was never the same.

But the story was not over just yet.

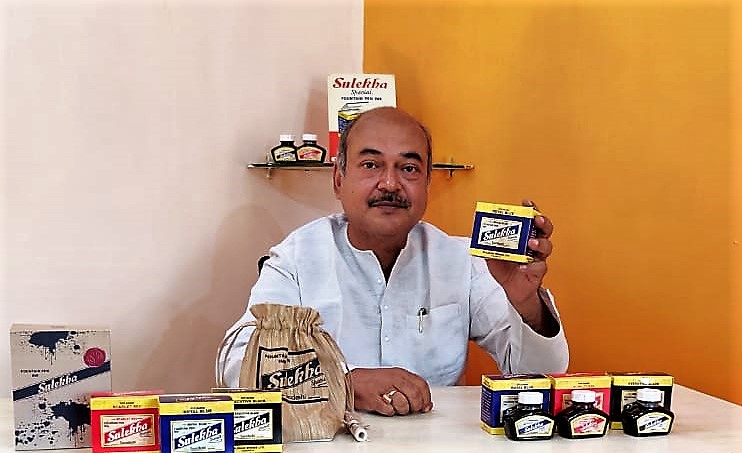

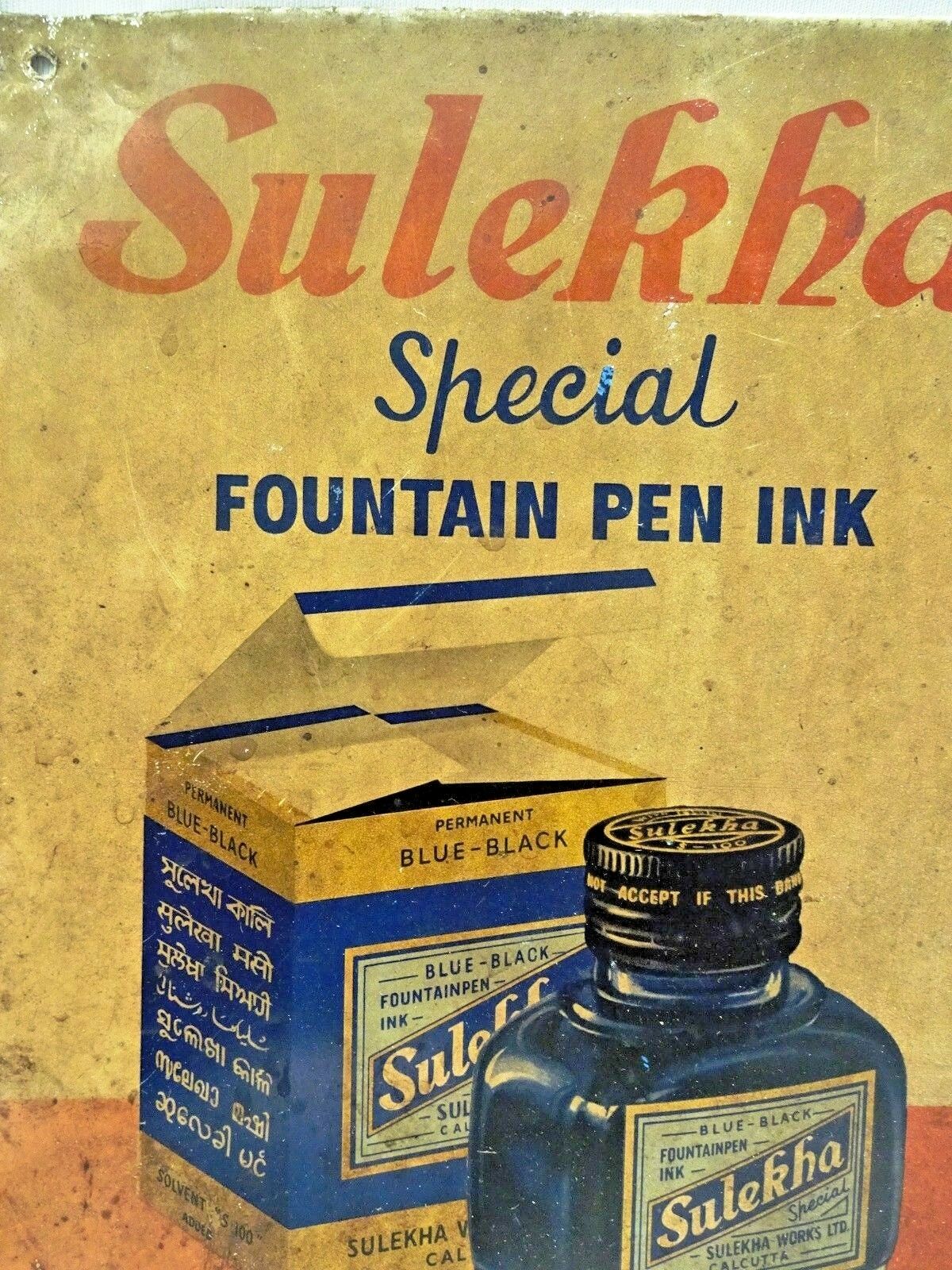

In November last year, the company formally relaunched its famous Swadeshi line of inks including Scarlet, Red, Executive Black and Royal Blue. It also added a patriotism flavour by packing the ink in another symbol of resistance, the khadi pouch made in Santiniketan.

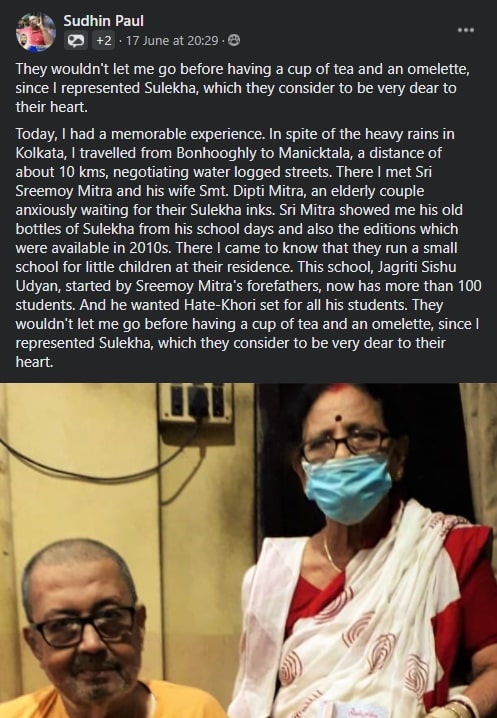

The company received an overwhelming response and orders began pouring in from different countries, including Greece, Australia, the UK, USA, Bangladesh, Nepal and of course, India. There are close to 2,000 members on a Facebook group called ‘Sulekha Ink Lovers’ who share their fond memories with the ink every day.

“We never really stopped manufacturing ink. It was being done in limited volume but in the last few years, the demand for fountain pens has been increasing as people want to switch from the plastic ones that cause pollution. Besides, the Aatmanirbhar sentiment has flared up. Several former users of Sulekha have reached out to us. We spread the word through social media and are back to delivering across India. We are also in talks with schools who want to introduce fountain pens among students and ensure that writing does not become a thing of the past,” Kaushik, Nanigopal’s grandson and current MD of Sulekha Works Limited, tells The Better India.

Ink made for the heart of India

Nanigopal and Sankaracharya’s parents, Ambica Charan Maitra and Satyabati Debi were also freedom fighters. When they learned of their children’s encounter with Gandhi, they were filled with pride. They poured their life savings into starting Sulekha. Nanigopal and Sankaracharya were joined by their mother and wives, Purnima and Urmila, in the manufacturing process. The women also helped in door-to-door selling in the initial days.

“The manufacturing was done in a cramped room. Initially, they sold it near train stations and to college students, doctors, lawyers, and writers. A factory was later set up. Five years into the business, the Maitras shifted to Kolkata in Bowbazar, followed by Kasba and Jadavpur. In 1946, the company became public limited and had more than 1,000 shareholders. Subsequently, we set up two new units in Sodepur (North 24 Parganas) and Ghaziabad, Uttar Pradesh. The ink left its indelible mark in the Middle East, South Asia and Africa as well. One of the company’s milestones came when the United Nations invited Sulekha to set up two ink factories in Africa,” says Kaushik.

If the company’s foundation was in the spirit of nationalism, it flourished solely because of its outstanding quality. The company invested a lot of money in research and development to solve issues such as leakage, smudging, and more.

“Gandhi’s picture on the bottle helped people associate Sulekha with the freedom movement. But in order to sustain, we had to do justice with the fountain pens, which stand for craftsmanship and precision. So all our energy, passion and hard work were channelled into the hand-made manufacturing process, which was tedious and time-consuming. The ink would be filtered twice, unlike machine-made ones, which take barely five minutes. Then we would add a secret solvent that ensured the ink dried quickly on paper and wouldn’t clog the refill. We use the same solvent and process even today,” says Kaushik.

Introducing colours such as orange, green, and red also helped, as back then, blue and black were default. Sulekha’s shade of blue was deliberately kept darker and the fragrance was stronger to help consumers identify with the brand easily.

The company stuck to traditional marketing gimmicks such as advertising on buses, trams and newspapers. It also formed an emotional bond with its consumers by organising writing competitions, and invited report writing from children.

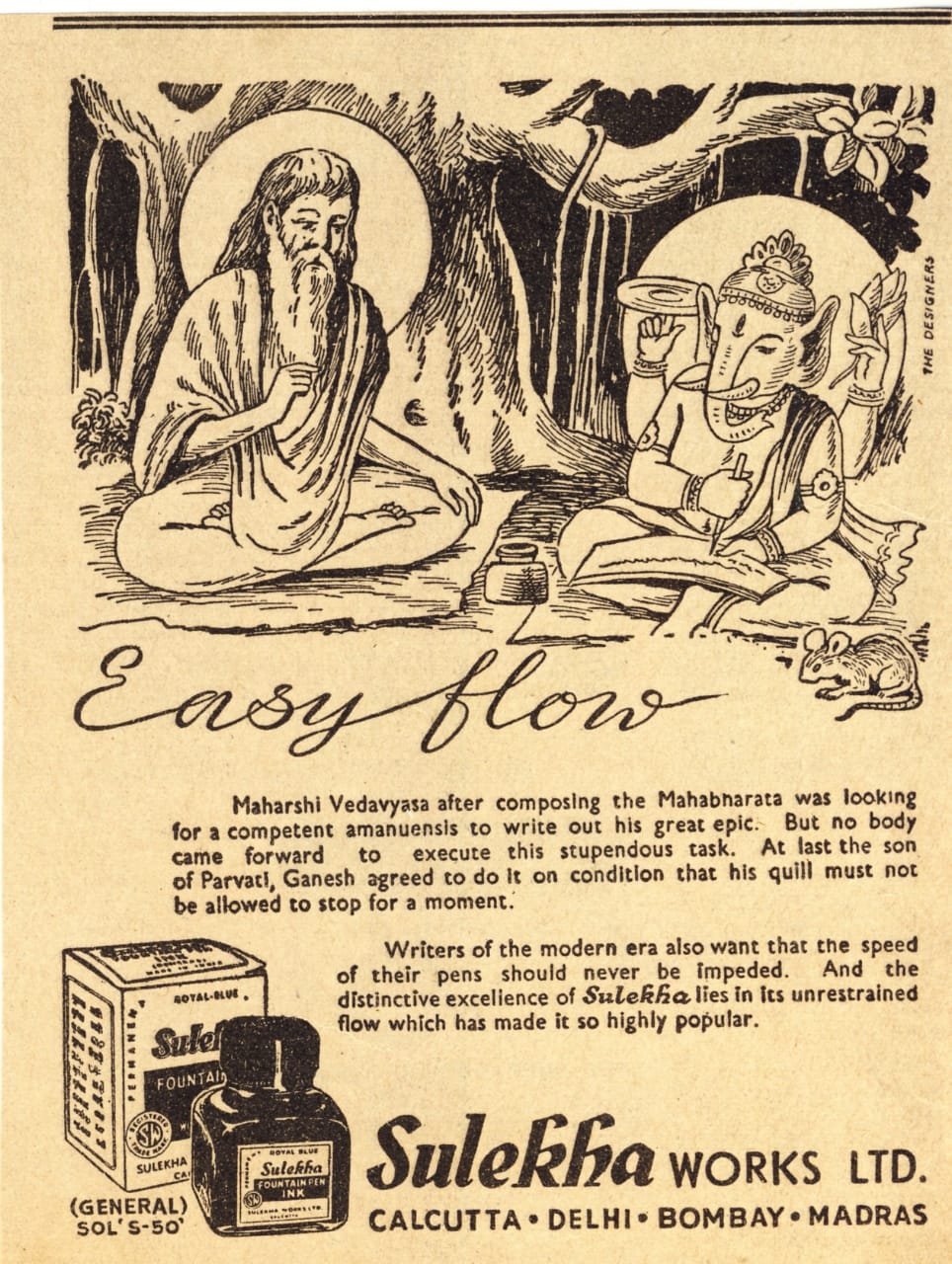

In one such print ad, the company connected mythology with the modern era. In the first half, the ad shares trivia about Mahabharata, in which Lord Ganesha agrees to write Maharshi Vedavyasa’s composition on the condition that his quill must not be allowed to stop. In the second half, Sulekha establishes that modern writers also want speed while writing, and thus, Sulekha offers unrestrained flow.

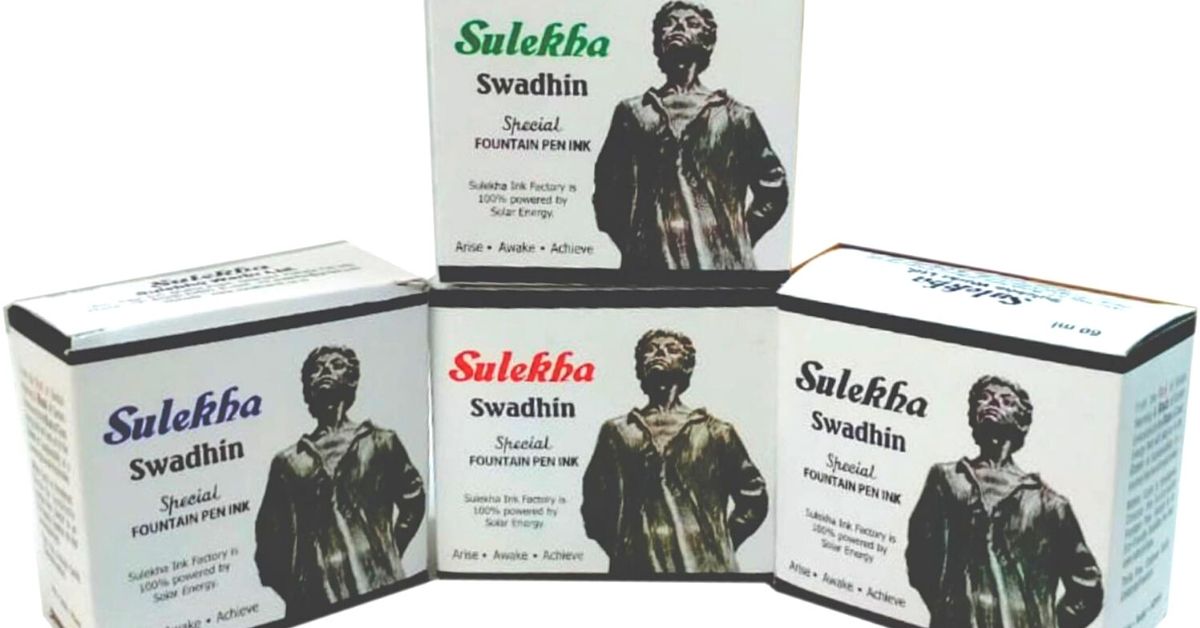

The history-modern connection was mirrored in its latest marketing strategy as well. Its limited edition ‘Sehlab’ bottles were printed with freedom fighters’ names. Meanwhile, under the ‘Swadhin’ range, each of the four colours stood for environmental consciousness. Black for carbon footprint, red for global warming, blue for clean energy and green for sustainability. It will soon launch the ‘Samarpan’ series, dedicated to Mother Teresa which will include blue and black inks.

The last strands of an era gone by

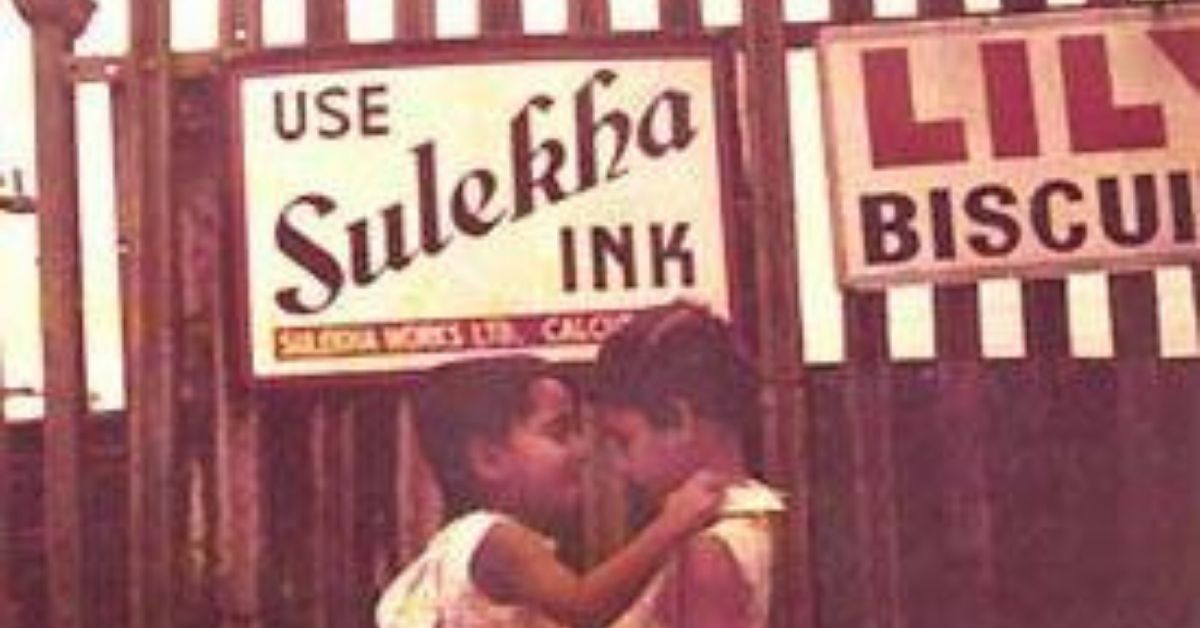

It is very rare to see a consumer brand go beyond fulfilling people’s needs and making profits, while cementing a permanent place in our hearts. Sulekha happens to be one of them. That is the only explanation behind Jadavpur Sulekha More, a colony in Kolkata named after the brand.

Not many know this, but the company hired several refugees of the 1971 war between Pakistan and Bangladesh, keeping their indomitable spirit intact.

“I am still surprised by people’s love for us. I remember a doctor who refused to charge us fees when he came to our house to check on my grandfather. He told us that our laboratory had hired him part-time and the salary helped him finance his education. Recently, a customer insisted one of our distributors have a meal when he delivered the ink to them after nearly two decades. There are several stories like these that keep us motivated,” Kaushik says.

For Ananya Barua, receiving a Sulekha pen was a matter of pride. She says, “I grew up very close to the Sulekha factory and most of my school stationery was of this brand, which has effortlessly woven itself into the Bengali social fabric. I’ve always had a fascination for fountain pens. I was 15 when my grandfather, who was a published Bengali author, gifted me my first ever fountain pen. Getting that from him was symbolic and poetic considering I went on to become a writer myself.”

With new mediums to write, today’s generation may not associate themselves with the joy of ink-stained fingers and blotched clothes. As the future of handwriting looks bleak with the advent of e-notes, emails, and laptops, Sulekha’s comeback seems almost dramatic. It may be one of our last chances to regain the charm of physical writing.

All images are sourced from Sulekha Works Limited. You can follow them here.

Edited by Divya Sethu

No comments:

Post a Comment