The year is 1614, and the Kingdom of Kakheti, a hilly region situated in eastern Georgia, is under the threat of invasion from Shah Abbas I, the Emperor of Persia considered by many as one of the greatest rulers of Iranian history and the Safavid dynasty. (Image above of Queen St. Ketevan’s remains in Goa courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

While Prince Alexander and Prince Levan are tortured to death, Queen Ketevan, a grandmother in her 60s and a devout follower of the Georgian Orthodox Church, is held captive in the city of Shiraz. After a decade in Shiraz, she is given the option of converting to Islam and joining the harem of Shah Abbas I, which she refuses.

So the story goes that following her refusal, Queen Ketevan was strangled and killed on 22 September 1624 (Gregorian calendar).

However, a year before her execution, two Augustinian friars had come to Shiraz to start a mission.

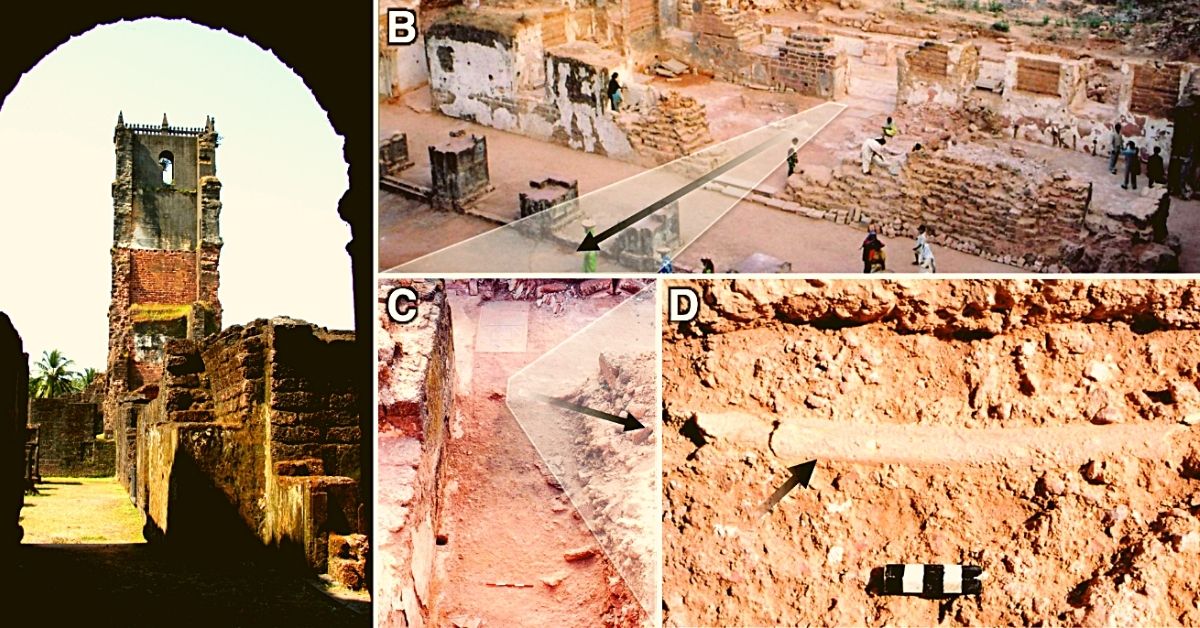

During their time in Shiraz, they had grown close to the queen, gained her trust and became her confessors. After her death, these friars unearthed her remains, and three years later, in 1627, brought a part of them (the right arm bone) to St Augustine Church (completed in 1602), which housed a historical Portuguese convent, in Old Goa.

These remains were kept inside a stone sarcophagus “on the second window along the Epistle side of the chapter chapel in the St Augustine convent,” according to this 2013 paper published in the Mitochondrion, a peer-reviewed international research journal.

The paper was authored by a team of Indian geneticists from the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology (CCMB), archeologists from the Archeological Survey of India (ASI), and academics from the Banaras Hindu University and Estonian Biocentre

On 10 July 2021, nearly 400 years after her death, India’s External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar handed over the relics that were found at the famous and ruined St Augustine church complex in old Goa in 2005 to the Georgian government.

These remains were identified by a team of molecular biologists from the Hyderabad-based Centre For Cellular And Molecular Biology (CCMB), led by Chief Scientist Dr K Thangaraj. The Better India speaks to Dr Niraj Rai, first author of the publication, who at the time was part of this team from the CCMB, to understand how these remains were identified.

Searching for the Queen’s remains

Queen Ketevan is considered a saint by the Georgian orthodox church, and her martyrdom has been recognised in multiple works of Western literature. Despite medieval Portuguese records — which were collated in a 1973 book by Portuguese-American historian Roberto Gulbenkian — citing the exact location of her remains at the St Augustine Church in Goa, finding them was a challenge. In the book, Gulbenkian talks about how he had discovered that the Augistinian friars had taken fragments of her hand and buried those relics in Goa.

His book created much excitement in Georgia, which was then part of the Soviet Union. From 1980 onwards, teams from the Soviet Union began descending down to Goa in an attempt to find the relics and zeroed in on the ruins of the Church of St Augustine. With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, various delegations from Georgia have partnered up with the Archeological Survey of India (ASI) to locate Ketevan’s relics at the church.

So how did the church fall into ruin? Why was it a challenge to locate the relics? “This historical convent was founded by a group of Augustinian friars, who arrived in Goa in 1572. Over time, it was enlarged and rebuilt, becoming one of the most noteworthy buildings of old Goa. In 1835, the church underwent partial demolition, and in 1842, the main vault of the church collapsed; the convent rapidly transformed into ruins. By this time, the valuable articles belonging to the religious complex had been either sold or lost,” notes the 2013 paper.

The paper adds, “After several attempts and a topographical survey within the Augustinian convent, the chapter chapel and window mentioned in literary sources were located by archeologists of the ASI, Goa-circle, in May 2004…This area was systematically explored and searching for the black box (stone sarcophagus), either intact or broken, was the primary interest of the excavation team. Further, while clearing the collapsed wall in which the second window was present, a long arm bone was found [in two pieces] in the sediments and was registered as QKT1. Since the relic box was made up of stone, it was broken into pieces due to the collapse of the wall. Fortunately, the team had found the intact lid, which provides a clue that the relic box might have been placed at the second window.”

During the excavation, two other bone relics (QKT2 and QKT3) were also recovered from outside the second window, with two intact black boxes and their lids.

Identifying the bones

These sets of bones were discovered by the ASI in 2005. In November 2006, the ASI took these bones wrapped in cotton to the Hyderabad-based CCMB for further identification.

At CCMB, Chief Scientist Thangaraj and his team decided to solve this problem by extracting mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from the bone samples.

“There are more copies of mtDNA in a cell as compared to the other sort, so it’s easier to work with when genetic material is not forthcoming. The other thing about mtDNA is that it is usually passed down unchanged from mother to child. But on the rare occasion, it will undergo a random change, and this will mark all the woman’s descendants from then on. The tag marking a new branch of descendants is called a haplogroup. Identifying haplogroups in a person’s mtDNA can help geneticists place her geographically, which is what the researchers hoped would happen with the bone samples they had,” notes this article published in the Mint by author Srinath Perur.

Although the CCMB spent three years (2006 to 2009) working on those samples, they were unsuccessful in sequencing the mtDNA from the bone samples. In 2011, the CCMB team attempted this process again to obtain a more definitive result on the identity of the bone specimen, and over the course of two years, were successful.

The first bone they recovered at the church complex (QKT1) carried a haplogroup called ‘U1b’, which they had never witnessed in contemporary DNA samples found in India. Scientists extracted the DNA and cross-verified with the CCMB’s own data bank of 22,000 DNA sequences of Indians. They couldn’t come up with a match.

“Since the chapter chapel was in ruins, it was very difficult to identify the exact location of the relic. Instead of one bone sample, archeologists at ASI found three. Meanwhile, in medieval records, the location of only one bone sample was documented. Our task was to test whether any of these three bone samples matches with the Georgian queen or not. We started working on these samples in 2012, and found that the other two bone samples were matching with locals found along the coast of Goa and Mangalore. One sample, however, was showing very unique characteristics. We found very strange genetic signatures that are not generally present among South Asians. We have a data bank of 22,000 DNA sequences of Indians from across the country. This bone sample showed no affinity towards any of the 22,000 DNA sequences in our data bank,” Dr Niraj Rai, who is currently at the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences in Lucknow, tells The Better India.

Next, they had to compare this sequence with mtDNA from present-day Georgians. So the St Ketevan Church in Tbilisi, the capital city of Georgia, agreed to send over saliva samples of 30 citizens from the country’s eastern regions.

Among the 30 Georgians, some had the U1b haplogroup, thus showing the scientists in India its prevalence in the region. Meanwhile, the other two bone samples (QKT2 and QKT3) were found to have haplogroups found in western India, and thus they probably came from locals. Additional tests went on to confirm that the QKT1 bone sample came from a woman.

“Unfortunately, we couldn’t find any surviving descendents of Ketevan. However, we were able to gather the saliva samples of 30 individuals from east Georgia. Luckily, we found a complete match of this bone sample with 2 individuals from the same geographical region. We found that this bone sample has the strongest affinity with Georgia. We then proceeded to test whether this belonged to a male or female. After our analysis, we found that the sex of the sample is female. Meanwhile, the other two bone samples were of males. Even though we figured out that this bone sample belonged to a woman from Georgia, how can we be sure that it belongs to Ketevan? So, we clubbed all the literary evidence citing the exact location of the bone sample and the analysis we did to confirm with about 99% accuracy that this relic belongs to Queen Ketevan,” says Dr Rai.

Finally, in 2013, it was established that the right arm bone found in two pieces eight years earlier, came from an east Georgian woman. These bones carried a female DNA, were genetically related with the person of Georgian origin, and didn’t match with any Indian DNA sequences. Given the precise nature of the medieval Portuguese records citing the exact location of the bones, scientists were sure that these bones belonged to Queen Ketevan.

They initially decided to submit their paper to Mitochondrian in 2013. It took almost six months to get this study published, with three external experts from Europe and the USA assessing the merits of their findings.

“After they reviewed our work, they raised many questions. We answered them and justified our findings, while our raw data was tested. Once everything was confirmed, our paper was accepted for publication. Extracting DNA from a 400-year-old degraded sample was a difficult and tedious challenge. Working with mtDNA, we prefer tooth samples or a hard bone called the petrous (ear bone). The tooth has enamel coating containing calcium carbonate and calcium phosphate. This makes it harder for bacteria and other microorganisms to penetrate, making the preservation of DNA extremely high. But long bones like your right arm are easy targets for bacterial decomposition. Regardless, our submission was ranked among the top 10 academic papers under the category of Forensic Biology during an International Society of Applied Biology conference in 2014,” says Dr Rai.

Nonetheless, he says it’s impossible to arrive at 100% certainty whether those relics belong to Queen Ketevan. Some questions, Dr Rai believes, remain unanswered. For example, why did these Augustinian friars come with her relics to Goa all the way from Iran, when they could have gone to Europe or other neighbouring countries?

Having said that, this is probably the closest the Georgian government is going to come in retrieving their famous martyr’s relics. It has taken more than seven years to hand over these relics to the Government of Georgia.

In some ways, a part of Queen Ketevan may finally get to return home.

(Edited by Divya Sethu)

No comments:

Post a Comment