For five weeks, starting 30 April 1924, Sir Chettur Sankaran Nair, a distinguished lawyer and judge of the Madras High Court—who also served as the first (and only) Malayali president of the Indian National Congress (INC) in 1897—was engaged in an epic courtroom battle at the Court of King’s Bench in London.

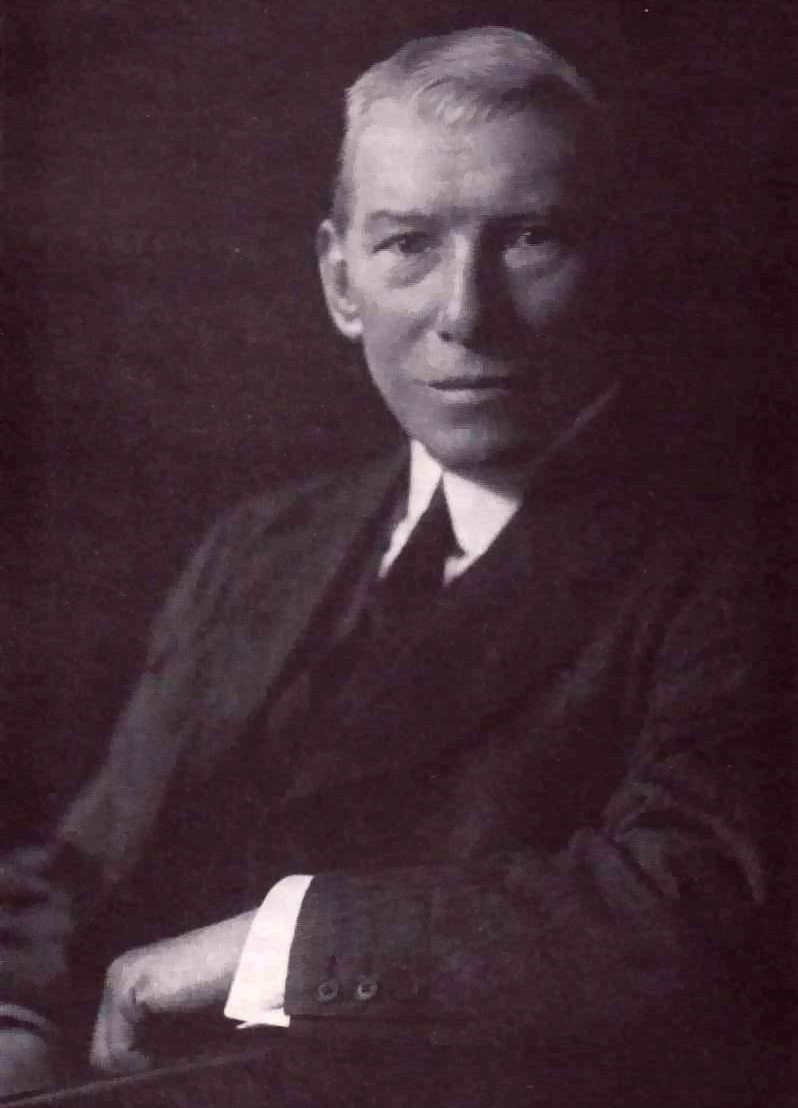

(Image above of Sir Chettur Sankaran Nair via Wikimedia Commons and National Portrait Gallery.)

Sankaran Nair was in court because of accusations he had levelled against Michael O’Dwyer, the Lieutenant Governor of Punjab from 1913 to 1919, in his book ‘Gandhi and Anarchy’. In the book, Sankaran Nair held the high-ranking British official responsible for the atrocities committed at the Jallianwala Bagh massacre on 13 April 1919.

Angered by the accusation, he sued Nair for libel. Battling a high-ranking Englishman in an English court that was presided over by an English jury, the odds were stacked against him. But what emerged from this courtroom battle was as historic as Rabindranath Tagore relinquishing his knighthood following the horrors of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre.

Even though the case has been well documented in Nair’s autobiography, a biography written by his son-in-law and Independent India’s first Foreign Secretary KPS Menon, and ‘The Case That Shook The Empire’ written by great-grandson Raghu Palat and his wife Pushpa Palat in 2019, it remains largely forgotten in recent public memory.

However, noted filmmaker and producer Karan Johar on 29 June 2021 announced his decision to produce a film that will “unravel the legendary courtroom battle” that Nair fought. The film will be adapted from the book written by Raghu and Pushpa Palat. Here’s a brief look into the life of a man who firmly believed in self-determination for India.

A Mind of His Own

Born on 11 July 1857 in Mankara village of Malabar’s Palakkad district, Kerala, Nair had a privileged upbringing. He was from an aristocratic family, whose members had served the East India Company and the subsequent British Raj.

Upon graduating from Presidency College in Madras (Chennai), he was drawn to a career in law. After obtaining his law degree, he was hired by Sir Horatio Shephard, who would go on to become Chief Justice of the Madras High Court.

His privileged upbringing, however, didn’t stop him from having a mind of his own. A man of strong convictions, his blunt and rather outspoken nature often rubbed his peers and colleagues the wrong way. No matter which way the wind would blow, Sankaran Nair was his own man. In fact, Edwin Montague, the secretary of state for India, once called him “an impossible person” who “shouts at the top of his voice and refuses to listen to anything when one argues and is absolutely uncompromising,” as Raghu and Pushpa Palat note in their book.

Even though he didn’t have many fans, Nair developed a stellar record both as a lawyer in the Madras High Court and as a social reformer. In 1897, he became the youngest president of the INC. More than a decade later, in 1908, he was appointed as a permanent judge in the Madras High Court, where he passed significant judgements supporting inter-caste and inter-religious marriages, and expressed his commitment to social reforms.

Four years after his appointment to the Madras High Court, he was knighted. In 1915, he was drafted into the Viceroy’s Executive Council (equivalent to the Union Cabinet of Ministers today), where he was tasked with overseeing the education portfolio. A firm believer in the rights of Indians for self-government, Nair played a fundamental role in furthering the participation of Indians in administering their own people.

It was his dissenting note to the Montagu-Chelmsford Report, which played a key role in the British Parliament’s decision to enact the Government of India Act, 1919. Besides introducing a system of dyarchy, this Act gave provincial legislatures the mantle of self-governance and provided Indians a greater stake in administering their own land.

This devolution of powers gave the strongest possible credence to the demand for self-governance. Nair recognised that this was a key milestone and a step towards constitutional freedom.

However, his role in the Viceroy’s Executive Council would come to a screeching halt following the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, and the British response to it.

As he writes in his autobiography: “Almost every day I was receiving complaints, personal and by letters, of the most harrowing description of the massacre at Jallianwala Bagh at Amritsar and the martial law administration…At the same time, I found that Lord Chelmsford [the Viceroy] approved of what was being done in Punjab. That, to me, was shocking.”

His resignation had serious repercussions for the British given that he wielded “more influence than any other Indian”, according to Edwin Montagu. Recognising the seriousness of his resignation and the bad press they were getting from it, the British got rid of provisions allowing for press censorship and ended martial law in Punjab.

Following the massacre, the British established a Royal Commission under Lord Hunter, which included English and Indian officials to investigate the horrific crimes committed on that day,

As KPS Menon writes, “That hour was, I think, the most glorious and golden hour of Sankaran Nair’s life. His star was never brighter.” Upon his return to Madras following the resignation, he was given a hero’s reception for taking such a public stand. “There were feasts and entertainment wherever the train stopped, and crackers were fired under the wheels of the railway, so much so that there was one continuous firing for hours,” he adds.

His Day in Court

One of the things he did after resigning from the Council was visit London and tell the British public about many of the ‘Un-British’ acts that were committed by their fellow high-ranking citizens in Punjab. Such was the impact he made that even future British Prime Minister Winston Churchill agreed that the Jallianwala Bagh massacre “is an extraordinary event, a monstrous event, an event which stands in singular and sinister isolation”.

However, his day in court arrived in unusual circumstances.

Besides criticising MK Gandhi’s approach to protest based on the premises of non-cooperation protest in his book ‘Gandhi and Anarchy’, he also hurled some serious allegations against O’Dwyer.

In court, O’Dwyer had Earnest B Charles, who employed an interesting defence.

As Raghu and Pushpa Palat write in their book, “Charles’ words were clearly meant to kindle the sympathy of the English jury for their own people. He exaggerated the perils the English bore to protect the Empire. Indians, of course, were portrayed as rebels, extremists and seditionists”. Sankaran Nair was defended by Sir Walter Schwabe, former Chief Justice of Madras High Court. The case naturally caught the eye of the British press, which reported on the severe pain and damage caused by O’Dwyer and his subordinate, General Dyer.

Unfortunately for Sankaran Nair and Sir Walter, the judge and jury showed no modicum of fairness and objectivity. Eventually, the jury decided against Nair except for one dissenting juror, Harold Laski, a notable an English political theorist and economist. Since this was not a unanimous verdict, he had another shot at a trial.

But he refused saying that he wouldn’t trust “another twelve English shopkeepers” to present a verdict in his favour. He even rejected the chance of issuing an apology and, instead, went on to pay damages amounting to GBP 7,500 — a huge sum at the time. He was also unbothered about the impact this verdict would have on his reputation back in India: “If all the judges of the King’s Bench together were to hold me guilty, still my reputation would not suffer.”

Even though he lost, the verdict strengthened the resolve of many Indians to fight for self-government since they understood the extent to which the British government would shield their own people from the monstrous atrocities they committed.

He passed away a decade later in 1934 at the age of 77, but not before leaving behind a real legacy of public service. His descendants (nine children and their children) would go on to serve India in various capacities such as Kunhiraman Palat Candeth, a senior officer of the Indian army, who played a key role in the liberation of Goa from the Portuguese in 1961.

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

No comments:

Post a Comment