In old Goa, a tiny island named Santo Estêvão or St Estevam was once a thriving land for growing delicious okra. Also known as Juvem, the island was once called Shakecho Juvo, which means the ‘isle of vegetables’, for its long, light green and seven-ridged ladyfingers.

The island was home to several farming families, including that of Manuel Francisco Dias and Escolástica Fernandes e Dias. The couple had five children, and on most days, struggled to make ends meet. But their son harboured a dream to follow a different path than what his family had been pursuing for generations. This young man was Miguel Caetano Dias, born on 9 July 1854, who later became a prominent doctor in Goa and went on to help the state fight the deadly Bubonic Plague.

“This dream was rather outlandish at the time, and a very daring ambition to hold,” Dr Luis Dias, Miguel’s great-grandson, tells The Better India. “The Medical School of Goa (Escola Médico-Cirúrgica de Nova Goa) had only recently come up and was not up to a very good standard. So if he wanted to fulfil his ambition, he’d have to travel outside Goa, which was occupied by the Portuguese at the time, to either British India, namely Bombay, or Lisbon in Portugal.”

But Miguel’s family did not have the financial wherewithal to support their young son’s dreams. “Many sacrifices had to be made so that my great-grandfather could travel to Lisbon to study. We have many stories passed on through oral history in our families that detail our financial struggles. For example, when my great-grandfather exceeded expectations with his performance in his school’s final exam, all his family could offer as a reward was a watermelon. That’s how impoverished the family was,” Dr Luis says.

Goa’s first native General

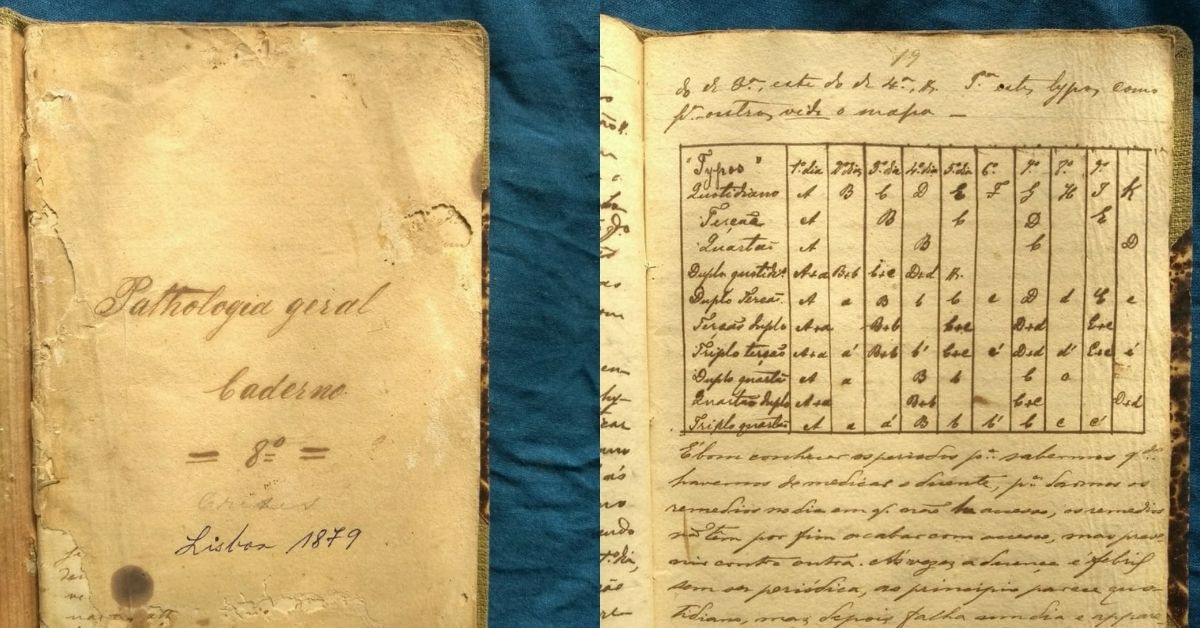

With his brother João Vicente Santana Dias’ support, Miguel was enrolled in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Lisbon, where he graduated with distinction in 1882. But he also found himself pressed for money and could not afford to buy the textbooks he needed. “Moreover, in those times, many of these texts were not even written in Portuguese but in French instead. So he had to study French first. It’s similar to how people today study in regional languages and when they move up to higher levels of education, they have to struggle with learning English,” Dr Luis explains.

So Miguel copied his text books by hand to make sure he could keep up with academics in the university. Today, while the Dias family has settled in different parts of the globe, each has a copy of these texts, which Dr Luis notes are a marvel to look at.

After Miguel finished his medical degree with flying colours, he was sent by the Portuguese to Mozambique, Africa, which was a Portuguese colony at the time. “The medical setup there was quite primitive, but he performed several life-saving surgeries with very little surgical equipment at his disposal,” Dr Luis says.

In 1888, Dr Miguel was sent back to Goa. Dr Luis notes that Portuguese Goa was not as thriving as British India. Hospitals were under military administration, and military titles were given to signify various postings.

Dr Miguel rose through the ranks rapidly and was appointed as Director of Health Services of Medical School of Goa and given the designation of ‘General’, the highest rank in the Portuguese medical cadre. He was the first and only native of Goa to receive this honour.

A dedicated fight against the deadly plague

Later appointed as Director of the medical school, he gained much respect due to his expertise as both a physician as well as a surgeon and performed several groundbreaking surgeries, including the first appendectomy in the state, where the patient lived to tell the tale. “Remember, this was a time before antibiotics and blood transfusions and anaesthesia. So if you opened the internal cavity, there were higher chances of infection,” Dr Luis says.

Over the course of his career, the Portuguese administration bestowed several honours and accolades upon Dr Miguel, notably for his work during the Bubonic Plague around 1908. He ran several anti-plague campaigns and sanitary policies, and these played a significant role in the adoption of modern European medicine across Goa. Dr Luis notes that Dr Miguel did not discriminate between the rich and poor and placed great emphasis on the relationship between public health and the civic administration.

His understanding of infections and diseases remained up-to-date, which helped him eradicate the plague from old Goa altogether. He also improved the sanitary conditions in Goa so vastly that the Portuguese Government bestowed several honours upon him, including the ancient order of chivalry Cavaleiro, Official e Comendador da Real Ordem Militar de S. Bento de Aviz (Knight, Administrator and Commander of The Royal Military Order of St Benedict of Aviz).

Another one of Dr Miguel’s notable achievements was his role in saving the Medical School, amid a tense colonial backdrop and severe hardships. Around the time he returned to Goa in 1888, the Portuguese government was on the verge of shutting down the Medical School of Goa after an inspection was conducted in 1897 by Portuguese doctor Cesar Gomes Barbosa, who found the institution below the mark and advised shutting it permanently.

This decision was overturned in 1902, supposedly at the behest of prominent Portuguese physician and politician Miguel Bombarda, who said the school would be the right environment to train doctors for Portuguese colonies. However, while Bombarda did not acknowledge this, it was Dr Miguel who had made these arguments first.

“The Medical Surgical School of Nova Goa, situated in a country where the reigning diseases reflect the tropical climate acts to foster the training of colonial doctors in such conditions, and so assists with the demands of African colonisation at little cost for the treasury,” Dr Miguel wrote. “Having once been understood as a significant element in assisting progress, no one ignores that this school has been useful not only for Portuguese India, but also to the remaining colonies of our overseas rule…When there was only horror of migrating to Africa, it was the offspring of the Nova Goa Medical Surgical School that bolstered the parcity of doctors in the overseas provinces.”

These were times where society was highly divided, and while Dr Miguel was a Christian, he did not come from an elite background as his predecessors. So he worked his way up to societal recognition through tremendous effort, and despite receiving several laurels, at many stages, his contributions were lesser noted.

Moreover, he was a strong advocate of modern European vaccination methods, as opposed to old methods of inoculation that were locally prominent at the time. He fought the popular notion that vaccination methods went against common rituals and could “pollute the body”.

Luis de Menezes Bragança, journalist and anti-colonial activist from Goa, said of Dr Miguel, “…As he attained a position of prestige and eminence, he hid not take pride in it, as he was fully aware of the obstacles he had to overcome to open a triumphant way in life. Life among the great did not dazzle him. He remained always the same – simple, ingenuous, unaffected before the great and the small, perhaps he lacked the superficial varnish of behaviour that many use to conceal hidden malice, the studied smile that often hides simulated revenge – all this that deceives the poor of spirit.”

Along similar lines, Dr Luis notes, “There are many stories in the family about my great-grandfather’s humility. He never forgot his roots, and throughout his career, honoured his own father. There was once an event to honour Dr Miguel’s life and work, and he made it a point to get up on stage to talk about a man greater than himself — his father. In another incident, he once saw a vegetable seller walking down the road, who was being eve teased and harassed. They were calling her a bhendekan, which means a bhindi seller. So my great-grandfather shouted from his balcony, ‘I’m a bhendekar too, come deal with me first’. That’s the kind of man he was — he was very proud of where he came from.”

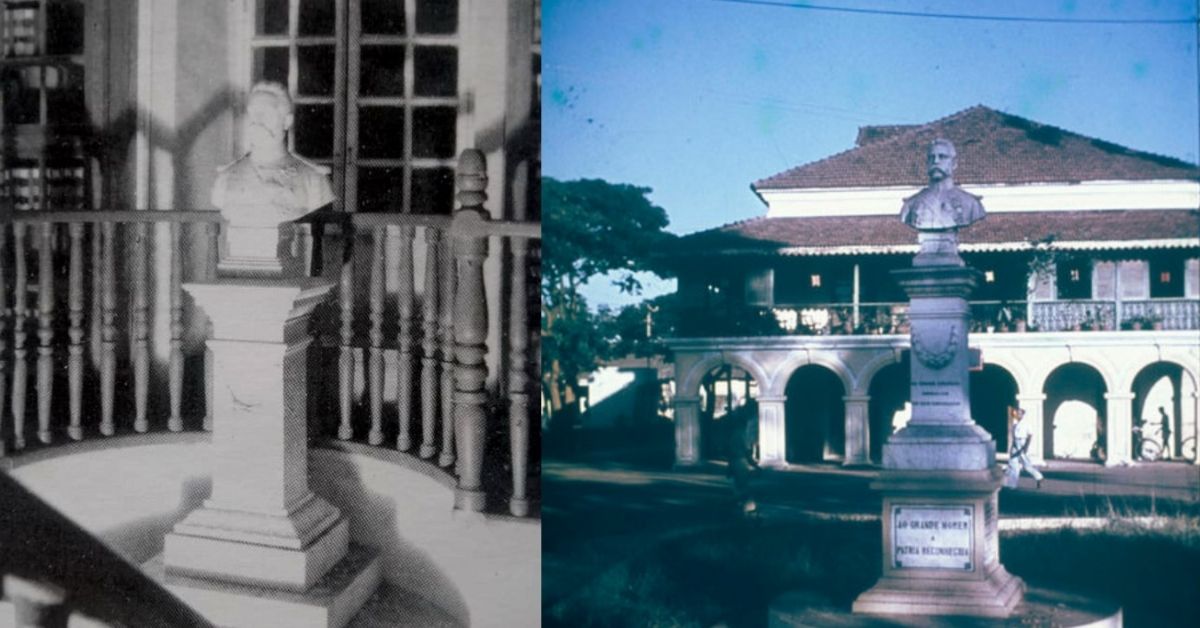

In line with Dr Miguel’s last wishes, upon his death on 26 July 1936, he was laid to rest in his native village rather than Panjim, where he lived through most of his thriving career. Today, a bust stands in Panjim to commemorate his life and achievements. It was commissioned by his admirers and the Portuguese Goa administration while he was still living, and stood at the Escola Medica (today the old GMC building) and was brought to the square in front of his house in September 1936, two months after his death. The bust is embellished with several medals and honours for his work in eradicating the plague from Goa and transforming its healthcare system.

Edited by Yoshita Rao

No comments:

Post a Comment