Vishram Gangavane, part of the Thakar tribe known for the storytelling art of Chitrakathi (‘Chitra’ means painting and ‘katha’ is a story) in Maharashtra’s Sindhudurg district, was once summoned by Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj in his darbar (court).

So with a veena in one hand and a hand-made bundle of paper paintings in the other, he marched with other performers for several kilometres through the dense bushes of Sahyadri Hills. Exhausted from walking and performing puppet shows in several villages, a tensed Vishram finally arrived at the king’s court, and stood before the ruler of the mighty Maratha empire.

Here, the king’s orders entailed that the nomadic tribe perform on all nine days of Navratri, but also double up as spies.

At the time, musicians and instrumentalists who used voice modulation to narrate epics such as Ramayana and Mahabharata through paintings and puppetry were quite popular. Chhatrapati Shivaji banked on the fact that these Chitrakathi artists would be going from door to door after the performance to play the veena and collect bakshish (like rice, cashew nuts, and kokam), which would allow them to extract political information. The ruler fondly called the group “Butterflies of the Forest”, because they would flit from one part of the forest to the other.

After Chhatrapati Shivaji, Sawant Bhonsales of Sawantwadi continued commissioning the artists as spies and even allotted them land in Pinguli near Kudal village in return for their services. It is believed that information relayed by the artists helped both the rulers prepare for battles more effectively.

Vishram, who contributed to the historic battles, would have never imagined that 500 years later in 2021, his great-grandson Parshuram would be awarded the Padma Shri, India’s fourth highest civil award, for reviving his legacy.

“I have heard epic tales from my parents of the bravery and valour of my ancestors, who wholeheartedly entertained audiences with captivating performances while secretly discharging duties for the ruler. However, after independence, Chitrakathi started declining with practically no monetary returns. Many artists switched to government jobs and today only a handful of them practice this,” says Parshuram, who single-handedly revived the craft in the 1980s. He possesses close to 1,000 paintings, some of which are as old as three centuries.

Parshuram’s sons, Chetan and Eknath, are the latest entrants in the culturally rich legacy of Chitrakathi. Chetan, who has a diploma in engineering, talks about his ancestors, the odds they had to overcome to keep the craft alive, and how they are inculcating contemporary designs to attract the millennial generation’s attention.

Mesmerising tales

While there isn’t any concrete evidence to trace back the date of Chitrakathi’s origin, the earliest account mentioning the use of Kalsutri toys as puppets was written by Sant Gyaneshwar in the 15th chapter of sacred Gyaneshwari, a religious text of 1290 CE.

According to folklore, the forest-dependent tribals in Pinguli drew pictures on leaves with lime and soot from oil lamps. Their creativity was reflected in the carved wooden strings for puppetry and leather base for shadow puppetry.

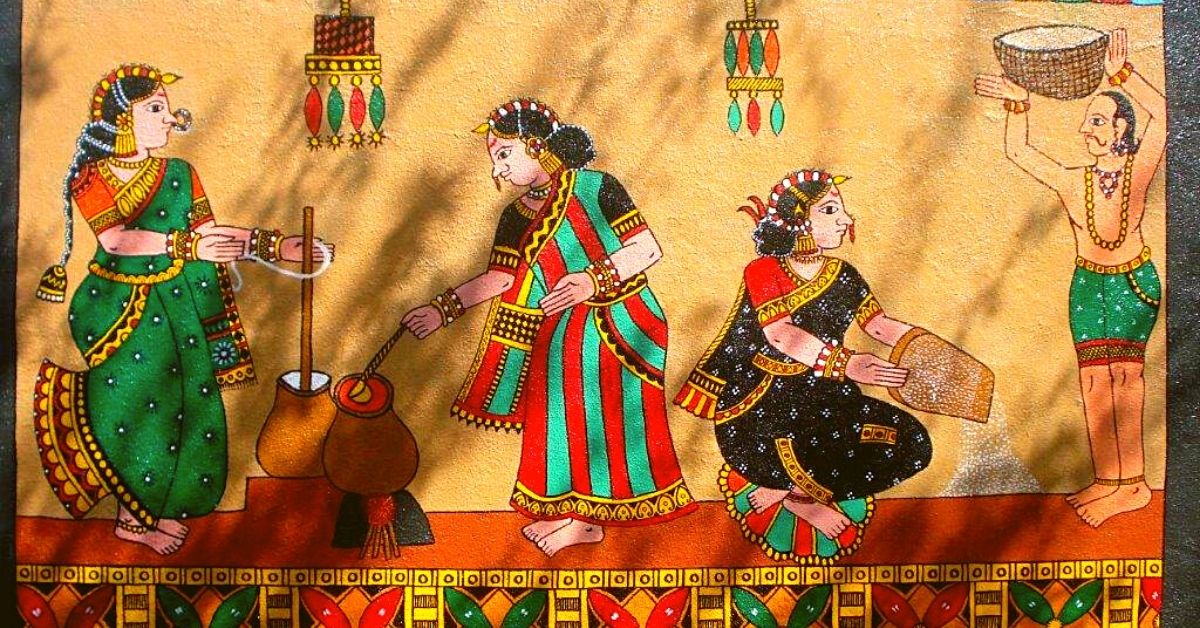

“In our community, there were 11 art forms that involved performing and drawing. One of these was Chitrakathi. With minimal resources at their disposal, artists found inspiration in nature. That’s why wood and leather skin from hunted animals became an integral part of the art. The dominant colours across generations have all been primary, as it is easy to extract green from leaves, blue from indigo and red from the Sahyadri soil,” says Chetan. Even today, colours such as red and yellow (from turmeric) are extracted from vegetables.

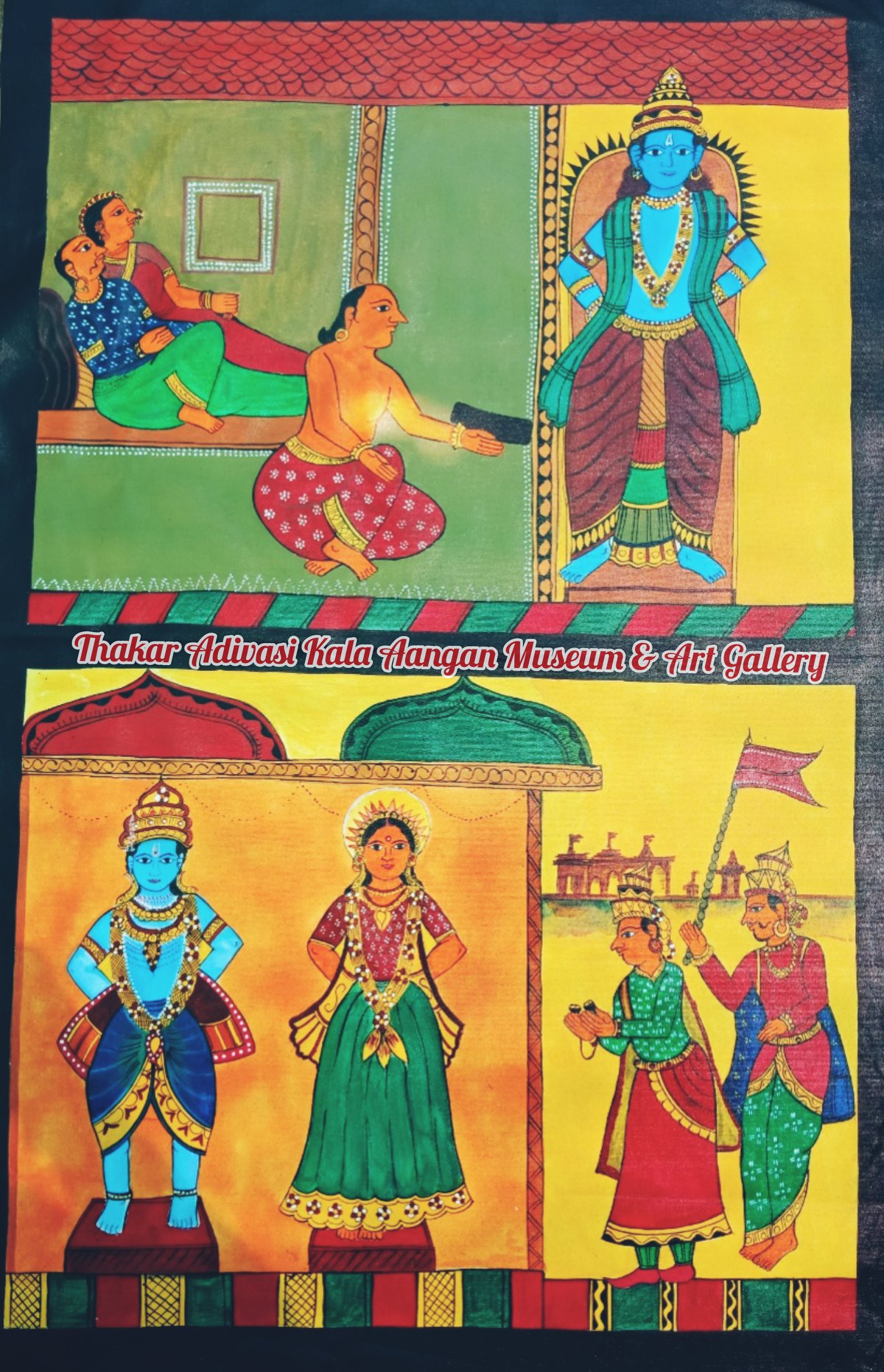

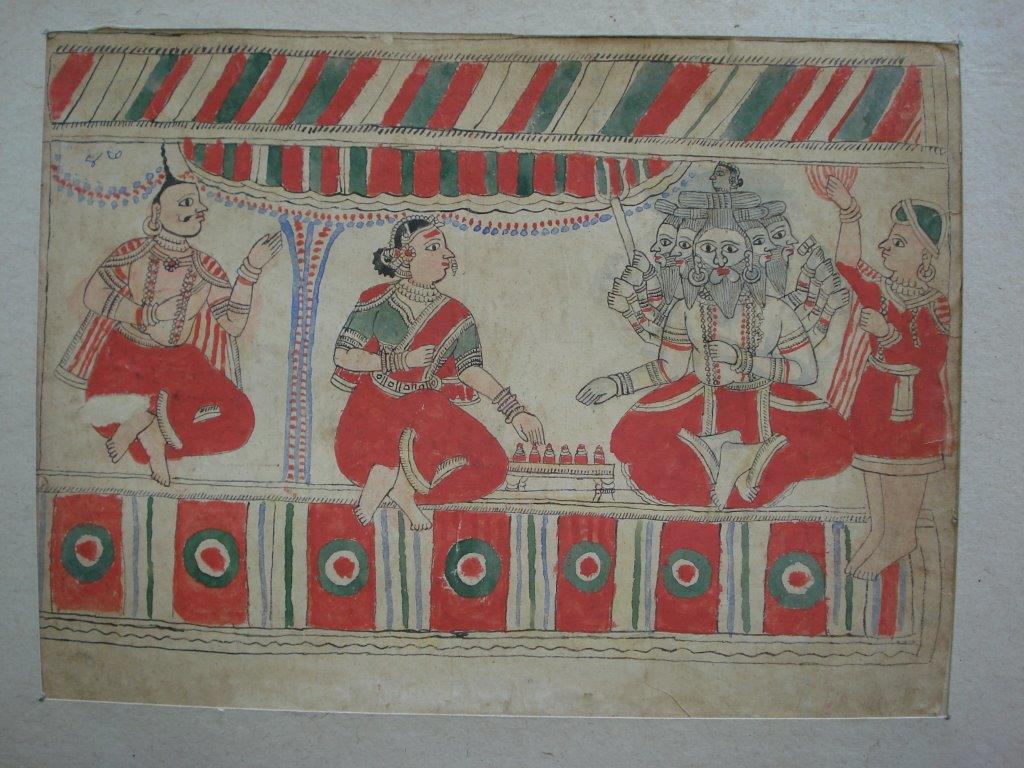

Under the painting-led narration, the artist forms a pothi (bundle) of pictures to narrate the folk story, religious texts (like Nandi Pura) or mythologies. The sequence of the paintings is according to the newly composed song, supported by instruments like the ektari veena, huduk (a two-headed small percussion instrument) and tuntuna. The artists sit on the floor and carry out the performance with paintings kept against a charaung (wooden table).

For the puppet show, the string puppets are made from wood and dressed in vivid colours. Their faces typically resemble mythological heroes, kings, and queens. Meanwhile, the two-dimensional shadow puppetry brings alive the haunting, tragic and brave tales on a screen of thin cloth backlit by a huge oil lamp at night.

With time, the surface medium first transitioned from leaves to paper and walls, and now includes items like handicrafts, pottery, clothes and more. Gawde Wada, a 100-year-old house near Pinguli, has a six-foot Chitrakathi painting. It also has a small temple that was the hub of ancient Chitrakathi performers. Chetan and Ekanth even attempted street art using calligraphy in the Devanagari script in Chitrakathi style.

“Back in the day, Chitrakathi was popular as an entertainment source, as it was easy to relate to and provided an enriching experience to its audiences. It evoked all senses including smell, hearing, and sight. It was truly a sight to behold. My grandfather’s voice was so loud that people sitting a kilometre away could hear the tales. But with the influx of television, internet and other sources, the performances decreased and art was further devalued,” says Chetan, who started performing at 12.

Due to insufficient earnings, the artists, including Parshuram, had to switch careers. He became a farmer and encouraged his children to pursue different fields as well.

Reviving Chitrakathi

Parshuram never really stopped performing, but would do it only on special occasions and in temples. His main source of income was agriculture. In the 1980s, the Ministry of Textile invited him to Delhi to exhibit his paintings.

“That trip was life-changing. For the first time, I realised that people outside Maharashtra are also interested in this art form. I sold paintings and puppets during that stint. After that, I grabbed every opportunity to travel around the country to display Chitrakathi. But while I was earning well, I told my children to get degrees,” says Parshuram.

However, in 2000, a tragic accident broke Parshuram’s left leg, which ended his farming career. He had to be shifted to a Mumbai hospital, where he stayed for nearly two years. The costly medical bills put the family under a severe debt crisis.

“We struggled a lot financially. There was no money to support even our education. My father opened a tea stall after returning to Pinguli. That’s when it was decided that my brother and I would look for stable jobs, which we did. But our genes couldn’t keep us away from Chitrakathi for long and I am grateful for that,” says Chetan.

In 2005, Chetan left his job and engaged full-time to find ways to revive the art. Meanwhile, Eknath continued his government to support the family. They converted their cowshed into a museum to display the century-old paintings, puppets and also sell merchandise.

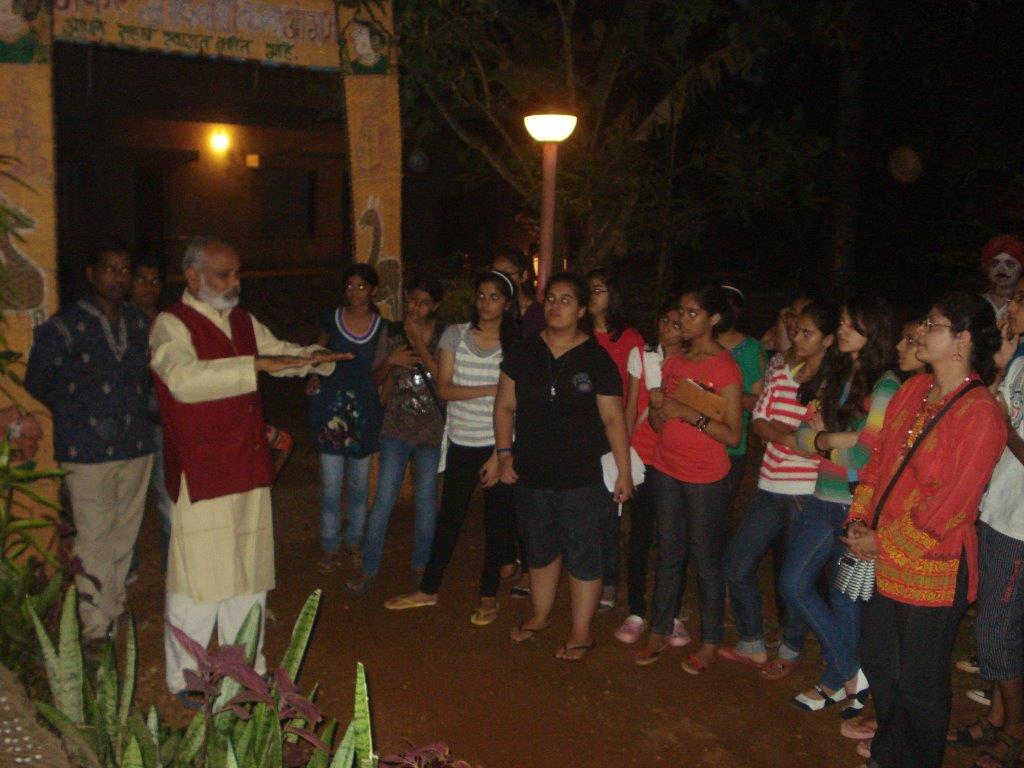

“Students of architecture, design and art would often visit or call my father to know more about the paintings, and he would happily explain. That gave us the idea of a museum. We started with a Rs 5 entry ticket and as the visitors increased, we raised it to Rs 20. Ministers, actors, and several known personalities visited the museum, which helped us spread the word,” says Chetan.

The geographical location of the museum on NH 66, which connects Goa and Maharashtra, also played a crucial role in attracting tourists. Additionally, the Deccan Odyssey tourist train makes a stop at Pinguli station. So they get several foreigners as well. In 2018, the family also started a homestay for tourists to give them a local taste of food, art and culture.

“We are trying to promote Chitrakathi through tourism, and before the COVID-19 lockdown, we would get an average of 500 visitors every month. We have modified our narratives and tales as per contemporary times. We have used the paintings and puppetry to spread awareness on HIV, cancer, polio, child abuse, coronavirus, and more. Just before the lockdown, we visited Kohima, Nagaland, where we did a puppet show comprising old and new texts,” says Chetan.

The family is now using social media platforms to teach the painting and takes workshops.

“The digital age is going to be a defining era for artisans to reach a wider audience. Our family’s story and art were even featured in Amazon Prime’s series ‘Lakhon Main Ek’. Our ancestors worked very hard to make Chitrakathi engaging in those days and used it to protect the subjects. So many years later, it warms my heart to know that this craft is making a comeback,” adds Parshuram.

All images are taken from the Gangavane family. Get in touch with them here

Edited by Divya Sethu

No comments:

Post a Comment