For the last 65 years or so, Maga Nayak’s routine has remained unchanged. Every morning, the pothi chitra artist from Odisha’s Nayakapatna village sits on the floor with a Lekhani or metal needle, and places a scroll made of palm leaves stitched together on his left thigh.

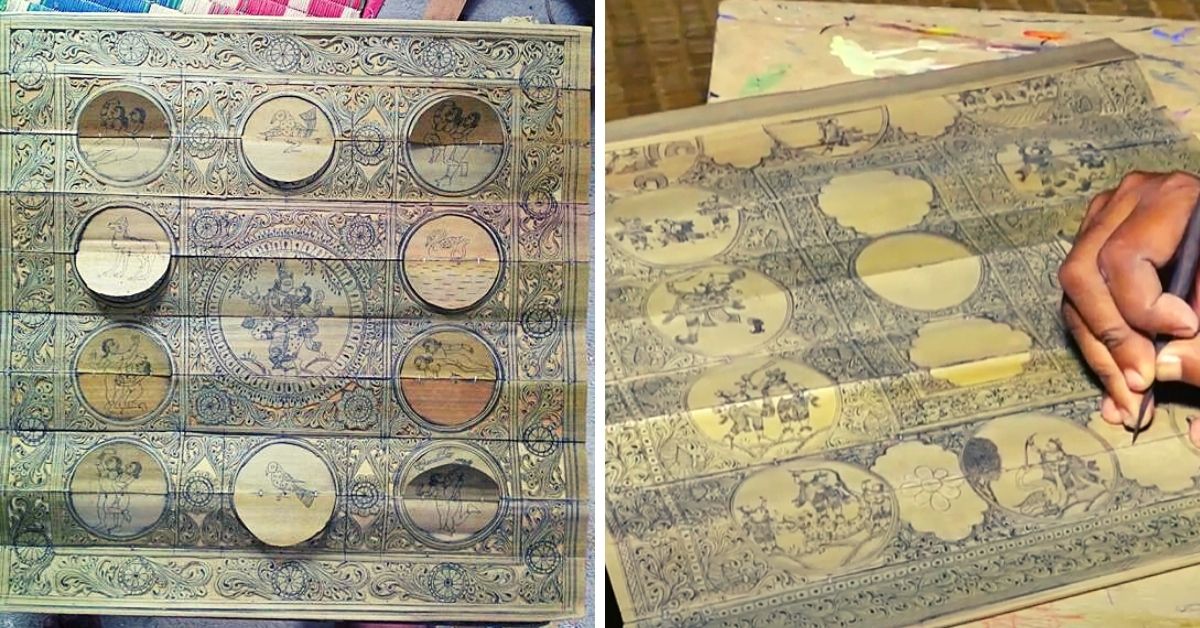

With utmost precision, he then inscribes either a chronological mythology story, or a manuscript in Odia, his native language, on the scroll. He spends about 7-8 hours daily, for anywhere between one month to a year, to complete his masterpiece.

I say masterpiece because each of these artworks can cost up to Rs 2,00,000.

Even at 76, Maga can leave anyone who comes across his work mesmerised with his exceptional skills. He is one of the few remaining pothi chitra artists in India and perhaps across the world who can engrave an entire manuscript or a mythology story on a single layer of palm leaf without tearing it.

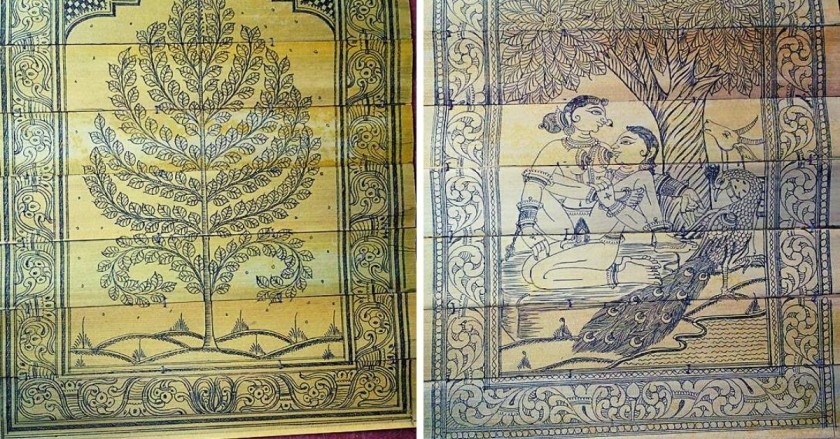

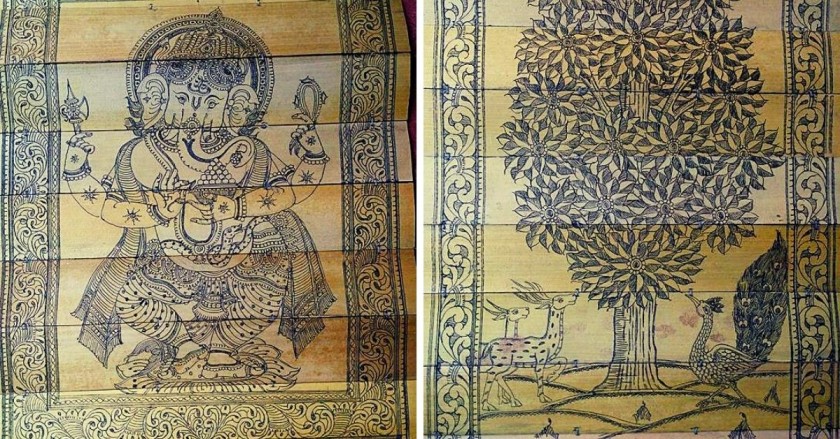

Traditional to Odisha, pothi chitra is the sister artform of Pattachitra. Lekhani or metal needle is the primary material used on dried palm leaves for engraving.

Maga has been instrumental in not keeping this 900-year-old art alive, but also helping 110 families of his village commercialise it. As a result of his tireless efforts, students from across India as well as the world flock to this tiny Odisha village to see the marvel for themselves.

The Better India spoke with Maga and his elder son Prashant to learn more about pothi chitra, the tedious steps that go into creating this lesser-known art form, and what makes the pieces last for several centuries.

It’s all in the family

The Nayak family has treasures of pothi chitra that are more than five centuries old. The texts on the pothi mostly include kundlis, horoscopes and shlokas that priests recite in temples during aartis. According to Prashant, his ancestors would travel to Puri, where the famous Jagannath temple is, to sell the pothis to priests. Their additional income came from writing auspicious dates and the future of the erstwhile rulers.

“Writing anything on pothis is considered very sacred and is a matter of religious pride. Even after pen and paper came to India, pothis have been a preferred choice. While the process is extremely difficult, the rewards are generous,” says Maga.

Maga was barely six when his father started teaching him the art form. Artistic genes, coupled with focus and hard work, soon earned him a name in the village. By the time he was a teenager, he was treated like a professional artist. He improved his skills with help from his guru, Jagannath Mahapatra.

Maga’s three children and one daughter took after him and learnt pothi chitra while growing up.

“My interest piqued when I was 10. I had accompanied my father to sell the pothis in Puri to foreigners outside their hotels. I can never forget the look on their faces — they were absolutely stumped when they saw the intricacy of the artwork. You can imagine the satisfaction and happiness you get from seeing people stunned at your skills like that,” says Prashant, who is the only person after Maga in the family who can engrave stories and designs on a single palm leaf layer.

To preserve this unique art form, both Prashant and Maga run an informal school where they train the villagers. Artists from all over Odisha spend a couple of weeks in the village to learn the process, which is still done without brushes and pens. They stick to natural colours made from stones instead of relying on paints.

The family makes close to 40 pieces every year that are sold via the B2B market. Instead of waiting for orders to make the pothis, they make them in advance and then sell it.

They have also ventured into making handicrafts like jewellery boxes, ludo games, chessboards, and more. They offer contemporary designs for people who want customised pothi pieces.

What goes into the gruelling process of making such breathtaking pieces?

- For nearly six months, the palm leaves are tied together and kept aside for drying, after which their strips are carefully removed without tearing the leaves.

- The leaves are then boiled for 2-3 hours in a mixture of water and paste made from turmeric and neem leaves. This makes the leaves anti-bacterial and damage-proof. The shelf life is now increased to 500 years or more.

- The newly matured leaves are once again kept for drying and then sewn together with a thread to form a scroll. To make double layers, two scrolls are stitched together.

- In the next step, the artisans take measurements and chart out a plan on the designing process. They use either desks or their thighs to do the engraving.

- Meanwhile, other family members prepare the colours. Black colour comes from kajal. The Nayak family adds gum from a wood apple tree, which prevents colour fading. They use coconut shells to make the mixture.

- Hematite stone gives colours like red and pink, sulphur gives yellow and blue is procured from indigo. Shankh (shell) is ground for white colour.

- The colours are directly poured onto the scrolls and spread across evenly with the help of a cloth. The engraved parts absorb the colour and the rest of it is wiped with a wet cloth.

- In the final stage, the piece is kept for drying.

Achieving designs that have perfect alignment with a needle is not everyone’s cup of tea. It takes years of practice, unflinching focus, and a thorough commitment to finish just one piece.

Unfortunately, over the years, the attention has shifted to Pattachitra due to several reasons.

“Pothi chitra is more tedious, gives less returns, and looks outdated in front of cloth scrolls. The artists also didn’t do much to make it mainstream. I wish the government had taken the same efforts they took to popularise Pattachitra. We would not have to struggle during the pandemic crisis,” says Prashant.

There are several magnificent but unsold pieces lying in the Nayaks’ home due to lack of buyers during the lockdown. The situation is so bad that the family is struggling to have three meals a day.

What makes this situation worse is the amount of laborious hours each family member puts in to achieve the highest level of precision in the scroll. Imagine sitting on floors with folded legs and a metal needle without taking eyes off from the pothi for hours, only to get bare minimum in return.

If you wish to help the Nayak family, you can reach Prashant at 993715695

Edited by Divya Sethu

No comments:

Post a Comment