Once known as a safe haven for Maoists, the Ajodhya hills in West Bengal’s Purulia district has now become a tourist hotspot, all thanks to the efforts of one man — Chitta Dey.

Using the ancient art of ‘in-situ’ rock carving, he transformed the face of the scenic hills situated between Balamrampur and Srirampur village, and in the process generated employment for nearly 25 tribal youth.

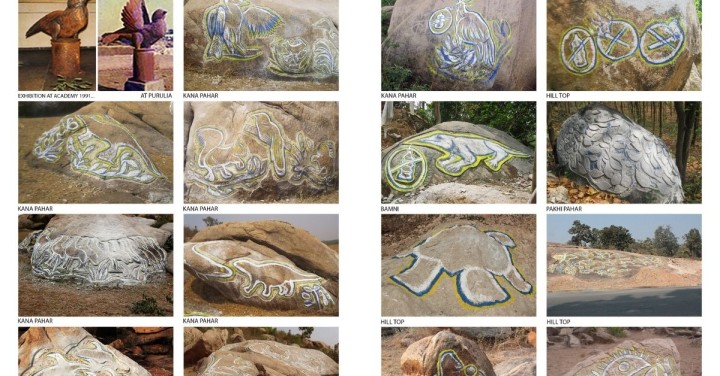

He engraved birds and animals on the gigantic rocks, as tall as 800 feet. Impressed with the 63-year-old talented artist, the government of West Bengal extended financial support for his process and also to preserve the rocks.

“Stealing and illegal smuggling of ancient rocks with carvings is a common practice in India. By illustrating art on Ajodhya hills, we have ensured that the precious hill will not be damaged by anyone. The stone carvings have now become a part of our heritage just like the Elephanta or Ajanta Ellora caves,” Chitta tells The Better India.

The dextrous artist, who was once labelled as ‘crazy’ for saying the rock was his ‘canvas’, was also turned away by the government and locals who failed to fathom why an artist like him was interested in ‘wasting’ his skills here.

Hill Hunting

Born and raised in a lower middle class family of Kolkata with eight siblings, Chitta was never encouraged to pursue his artistic abilities though he was locally quite popular for his work. His father passed away in 1975 and this further pushed him away from it.

He took up a job in theatres to design sets and support his family while saving enough to do a diploma course from Government Art College in Kolkata.

Here, he would discover the technique of in-situ carving and learn India’s prosperous heritage in stone sculpting.

“Stone carvings are usually associated with a process in which stones are quarried and sculpted somewhere else. This practice is common and uncomplicated. But if you glance around the globe, you will find remarkable sites where sculpting was done on site. These include China’s Giant Buddha, Crazy Horse Memorial in South Dakota, Naqsh-e-Rustam in Persepolis and Santoni in Sicily. Closer home we have Ajanta and Badami Cave temples. As per my knowledge, the last stone sculpting in India was done in the 11th century. I wanted to revive this artform and pass down the skills to the younger generation,” says Chitta.

Before embarking on his mission, Chitta worked in the local art scene and established himself.

The triggering point came in 1991 during an art show where he exhibited a metal scripture of a bird with wings as large as 22 feet tall. He was forced to dismantle the piece and assemble it again as it couldn’t pass through the doors of the Academy of Fine Arts.

When he was asked to reduce the size of his pieces at upcoming exhibitions, he realised he needed a larger canvas.

In the same year, he began the hunt for a suitable hill and visited multiple sites, from the Western ghats of Maharashtra, Rock area near Madhya Pradesh’s Narmada river to the metamorphosed rock hill terrain of Tamil Nadu.

He would observe the shape and size of the hills and imagine the drawings of birds and animals on them. He also studied and tested the rocks. Ajoydhya hills were the closest in terms of distance and also the most suitable for his next masterpiece.

It took him nearly 2-3 years and innumerable visits to various departments of the government offices to get the permits. In 1996, the State Government under then-Chief Minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee allotted him an 800-foot hill in the Mathar Pahar region and granted him Rs 2 lakhs for his work.

Stone Conservation Through Art

Chitta adopted a two-pronged strategy to sensitise the locals and increase the tourism in the region.

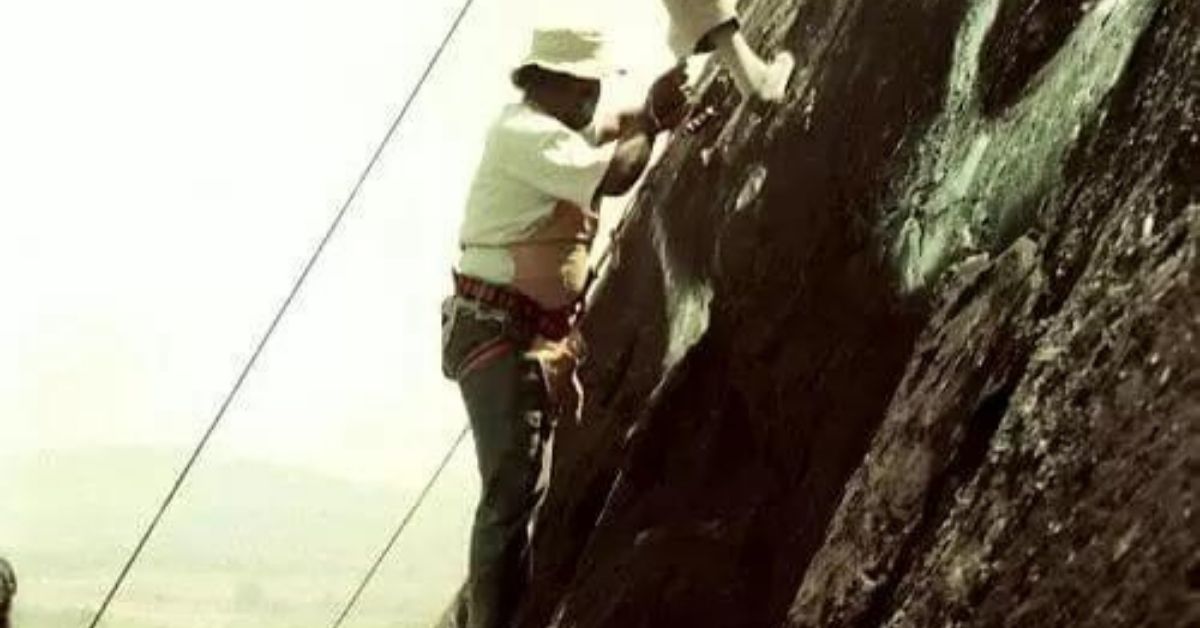

“The tribals have been living here for centuries and some families are still forest-dependent. Not involving them would be unfair. I taught stone carving and sculpting to 30 local youth over a period of three years. They were trained in handling hammers and chisel, rock climbing, and rappelling. I spent hours teaching designs, motifs, floral patterns on paper,” says Chitta.

The villagers labelled him as a ‘mad person up to something with the hill’. “Yet he would eat with us and sleep with us on the floor,” Paresh Mahato, one of the trainees, told Mint.

Chitta was impressed with the students’ patience and dedication and that motivated him to stay on this long and arduous journey of several years.

To attract the tourists, Chitta focussed on a nature-themed series called Pakhi Pahar (bird hill) in which he would draw over a hundred species of birds.

By 1999, he was ready with the drawings but the work began only in 2008 when he was granted more funds by the government.

While the smallest wingspan is about 55 feet, the biggest is spread across 120 feet of rock.

Chitta says one figurine can take anywhere between six months to a year, depending on its size and the weather conditions. Extreme heat and monsoons are a strict no.

“Stone carving requires immense amounts of stamina, strength and patience. On some days, we have to be okay if we just finish a tiny portion of the eye. It may look as if we are just sitting and doing the work but to think of it we are hanging several feet high in our harnesses in one position. We seldom take breaks. But we stop the work during unfavourable weather, otherwise it can get quite dangerous,” he adds.

The team spends at least a month visualising the bird on the hill from all the sides before putting it on paper.

“We use three enamel painting colours — white, blue and yellow, throughout the process. Yellow is to draw a model figure inside, which is the blue line from where we start cutting. White forms the basis of the structure. In the end, we wipe all the colours except white which takes the form of the figure,” explains Chitta.

Chitta and his team are presently working on their second project to make endangered animals like pangolin, turtles and spotted deers along with frogs, peacocks and squirrels. They are also using boulders and small rocks to showcase the local fauna.

Seeing the breathtaking rock art, the local government took several initiatives to beautify the hills like planting trees, making roads for proper connectivity and patrolling the area.

The tourism has increased two-fold, Chitta claims and says, “With more and more tourists flocking here, the presence of non-state actors has decreased. Plus, the locals are able to earn more because of the tourism boom. I am ecstatic to see that Pakhar Pahar is listed as a must-visit tourist spot on private and government tourism websites,” he says.

In their next project, the team hopes to recreate an underwater ecosystem depicting the lives of corals and fishes. However, he is worried about the funds. While the government has always supported his work, Chitta says they need more for execution.

“Financial help can guarantee that my team will pass on their skills to the next generation, who will continue this art for years to come. This is an important art form and we must do everything we can to preserve it,” he signs off.

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

No comments:

Post a Comment