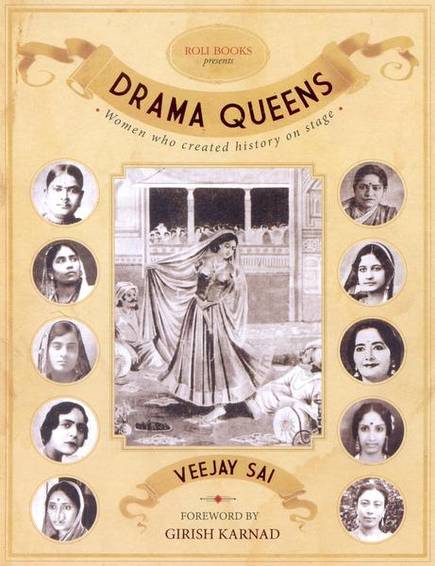

In his book Drama Queens: Women Who Created History on Stage (2017), author Veejay Sai encapsulates the allure of a woman who was once deemed the ‘Queen of Tamil Theatre’. He says her legacy was such that one might find her memory lingering in “the jingle of anklets, in the many silent gestures registered in the reflections of green room mirrors and in the side-wings and curtains on stage” even today.

But this ‘memory’ might be a faint one, for while the woman ruled the stage in all of Southern India at one time, today her life and struggles are practically unknown in not just the history of India, but also in the region where she once thrived.

Her performances had fans across the globe, and word of her charity and giving heart had spread far and wide. So how did she fade into such obscurity?

A safe haven for disenfranchised women

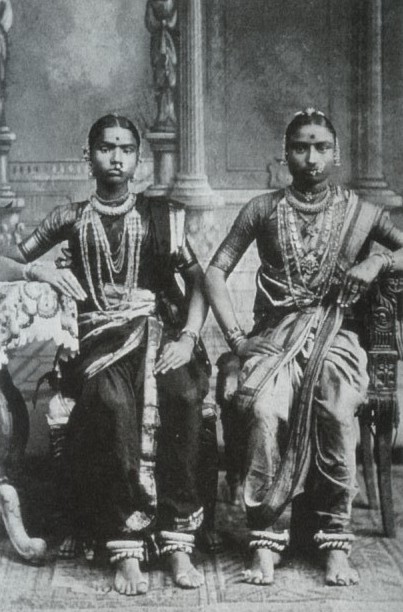

This woman was Balamani Ammal, also known as Kumbakonam Balamani. Born in the kavarai caste in Tamil Nadu’s Kumbakonam, she was soon ‘dedicated’ as a devadasi, and learned to sing and act in Sanskrit.

“Balamani was a woman of ambition and resolve, determined to transport the art she had inherited as a devadasi to wider audiences in imaginative forms,” wrote Manu Pillai in a short section on her in his book, The Courtesan, the Mahatma and the Italian Brahmin: Tales from Indian History (2019). “Breaking out of the temple, she became among the earliest to establish a formal enterprise, the Balamani Drama Company.”

This was a unique theatre company in many ways. For one, it was one of the first companies to be entirely run by women. While other theatre groups soon followed suit, Balamani’s company stood out because these women were exclusively “disenfranchised by anti-devadasi legislation”. While it could not eradicate the staunch beliefs held by the upper-castes, it gave destitute women a safe haven. Balamani was a patron of the arts and a smart businesswoman, who took her company to great heights.

Theatre as a form of dissent has evolved over the years. While theatre earlier focussed on depictions of mythological stories, in Tamil Nadu it soon evolved into political commentary and allegories against bigotry.

As playwright and theatre director Gowri Ramnarayan wrote:

“…No other region in India saw — as Tamil Nadu did — the power of theatre influencing the thoughts and actions of the masses. Inflamed by the ideologies of Dravida identity, reformist playwrights CN Annadurai (called the Bernard Shaw of Tamil drama!), and disciple M Karunanidhi did not write dialogues. They fired cannons and exploded bombs. Theatre became a political weapon, humanist in principle, atheist in belief. From this camp sprang Sivaji Ganesan and MG Ramachandran — the most mythicised actors of Tamil cinema,” she said.

Balamani’s theatre, too, was a form of such dissent. She “strode in from the wings to play male roles — with leather boots, velvet cloak and fencing sword”. She took up social themes through her plays — a detective play she once performed was later adapted for film. Poets and musicians who found themselves besotted with her wrote and composed detailed pieces of her beauty — one of which was even later sung by M S Subbulakshmi. She was known for being “bold”, and would subtly enact nude scenes that were more than taboo at the time.

It wasn’t just the “controversial” nature of her theatre that invited such a large audience. As Balamani’s theatre troupe grew, so did her wealth. But she used this for the benefit of women like her who faced inherent disadvantages in society.

She spent her best years living in palatial bungalows, complete with marble fountains, massive swimming pools, gardens that were home to peacocks and deer and had a staff of over 50 women who were at her service at all times. When she stepped out, she did so in a silver chariot with four horses. In the early 1900s, her popularity had soared to the point that the state began arranging special trains to ferry her fans to and from her plays. Two special trains called the Balamani Special Express would begin picking up audience members from areas such as Trichy and Mayavaram in the evening and then bring them to the theatre at night.

Fans would return home early in the morning after watching her performances all night long. Her attire became sought after among the women who came to watch her, and so far, no other woman had attained such popularity.

Manu Pillai details how Balamani was the first to introduce Petromax lighting onstage, and was one of the first to allot women-only spaces during her performances.

‘The poor knew the road to her house well enough’

French novelist Julien Viaud, under his pen name Pierre Loti, wrote of his brief meeting with Balamoni in his book The Land of the Great Palms, calling her “the good Bayadere” (an Anglo phrase for women known as devadasis). “The bayadere comported herself with so much reserve and dignity, indeed, that I saluted her, just as I would have done any lady of position. She answered my greeting in the Indian manner, touching her forehead with two ruby-covered hands; then, accompanied by her maids, took her seat in the carriage ‘For ladies only’. I follow the good Balamoni with my eyes as I leave the horrible neighbourhood of the station and make my way to the temple of the goddess. During the course of the day, some of her kindly deeds were related to me. This one amongst others: last month some European ladies who were collecting money for a Hindoo orphanage came to her, upon which Balamoni, with her beautiful smile, handed them a note for a thousand rupees (about eighty pounds). She is charitable to all, and the poor know the road to her house well enough.”

However, Balamani’s outwardness did not seem to sit well with everyone. As Sai details in his book, the views of the elites and puritans remained mostly disdainful towards her despite her fame. One of her plays, Tara Shashankam, created much controversy. The play detailed the story of Tara, a “celestial nymph who was cursed to take birth as a princess in the world of humans”, in which Balamani appeared nude before her lover and applied oil over his body. She enacted these scenes by keeping a semi-transparent curtain before her and stood behind her bare-topped, and in some scenes, she would wear a cloth that made her upper body appear bare. This triggered many debates about morality and censorship among the upper castes.

Moreover, years of charity eventually bled her dry. She spent exorbitant amounts of money on getting the girls under her care married, and as she aged, she was left virtually penniless. By 1935, the year she passed, she had moved from her palace to a small home in Madurai, and it is said that her loyal associates had to go around collecting enough funds to even arrange her funeral. Meanwhile, her grand house was later demolished to set up a commercial complex.

Sai writes, “A decade after Balamani’s death, at a conference held in Erode in 1944, a resolution was passed under the aegis of one Parthasarathy Iyengar, banning the play [Tara Shashankam] and condemning it as a nudist and immoral one. The resolution also endeavoured to ‘clean’ the art of theatre, ‘salvage’ it from the hands of devadasis and entrust it into the ‘safe sanitized hands’ of other upper-caste communities.”

However, even as Balamani died sans the fame and fortune that once surrounded her, she left behind a rich legacy of women who now have the courage to step forward.

Theatre became a form of protest for many women artists against the British in the 30s and 40s. Many were arrested for their songs and plays, and Tamil Nadu saw its first woman director, first super-star heroine, and the like.

As for Balamani, it is for us to wonder what might have been of her life had she not been a victim of archaic perceptions of purity and morality — perceptions we still struggle with even at the height of the 21st century.

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

No comments:

Post a Comment