Every year around April, the Great Indian Summer arrives, and the country gradually transforms into a furnace. The gentle morning sunshine of winter is replaced with a sweltering heat that sends thirsty street dogs scurrying for shade, their tongues lolling.

In such times, a cooling sherbet is almost like manna from heaven. A refresher once common in Indian homes is the khus sherbet, made from the vetiver grass leaves (Chrysopogon zizanioides).

One of nature’s best coolants, the leaves of khus, or vetiver, bring down body heat and are packed with natural antioxidants that reduce inflammation in the body. As for the roots, the essential oil extracted from them via steam distillation is an important base ingredient in perfumery.

Long before Zara and Dior used vetiver in their luxury perfumes, Indians had been using this aromatic grass in their everyday life.

According to historical records, India has been exporting vetiver for thousands of years.

Excerpts from ‘Periplus of the Erythraean Sea’, a first-century travel tome written by a Greek navigator, reveal that India shipped vetiver in large quantities. Ancient Sangam literature, written more than 2,000 years ago, also mentions vetiver as an ‘omaligai’ ingredient used to enhance the bathing experience.

In medieval India, the Mughals set up a department dedicated solely to developing scents for luxury and culinary purposes. Under their royal patronage, the ancient city of Kannauj emerged as India’s perfume capital — built atop the rich alluvial flood plains of river Ganga, the town was particularly suited to cultivating perfumery essentials such as rose, jasmine and vetiver.

Ever since, Kannauj has been concocting all sorts of evocative attars from vetiver, including the world-famous ‘Mitti attar’ that captures the exquisite scent of raindrops quenching parched soil. Read more about it here.

Kannauj’s vetiver ‘ruh’ is today prized in the world of international perfume business and is the base for iconic perfumes like Armani’s ‘Vetiver Babylone’ and Tom Ford’s ‘Grey Vetiver’. Interestingly, in her book ‘In The Scent Trail’, artist-journalist Celia Lyttelton writes that “scientists have isolated 150 molecules from vetiver, and there are still more mysteries to be unearthed from its roots.”

But vetiver’s story in India goes beyond its earthy perfume. It has roots in something that many Indians will find very familiar — desert coolers.

Until the 1990s, air conditioners were too expensive. Evaporative desert coolers were the best protection that many middle-class families could wield against the summer heat – perched precariously on stilts or window ledges.

These coolers were distinctive metal contraptions with vetiver mats fitted into their slatted sides, and in-built fans filled the air with a loud hum.

A part of the contraption was filled with water, drenching the vetiver mats. The hot air from outside would cool as it passed through the wet mats into the cage, and the fan would blow this cool, moist air into the room.

The relief brought by this sweet-smelling air is best summed up by these (translated) lines written by poet Bihari Lal Chaubey:

“As Vetiver blinds, that lend

To burning summer noons

The scented chill

Of winter nights.”

Interestingly, Abul Fazl, in his book ‘Ain-i-Akbari’, says that it was the Mughal Emperor Akbar himself who first devised the concept of using khus mats as cooling screens.

However, it was during the colonial era that the idea went high-tech. The British dread of hot Indian summers led to the creation of thermantidotes, a rather complicated name for an early version of desert coolers, with a hand-turned fan to drive air through mats of fragrant grass. These khus mats (or tatties, as they were called back then) were kept wet by a bhishtee, or a water carrier, engaged solely to sprinkle water on them.

Even today, homes in India’s hinterland use khus in window screens and thatched roofs to keep the hot summer wind out. More recently, sandals, hats and even masks made from vetiver have started gaining traction in Indian markets.

The grass also holds immense cultural significance in India, from festivals to folk art forms. For instance, during the Sama Chakeva festival in Bihar’s Mithila region, women come together to sing folk songs and make dolls from dried vetiver grass in a time-honoured tradition.

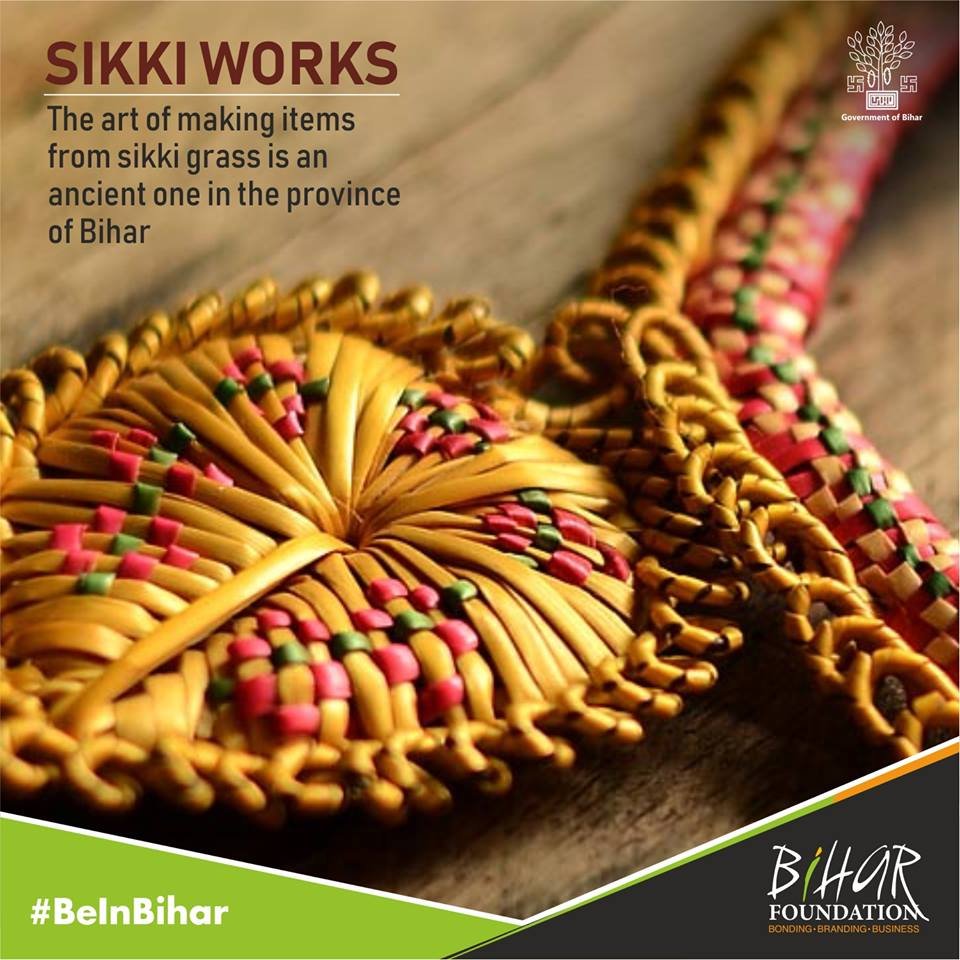

The people of Mithila also use vetiver stalks to make ‘Sikki’ handicrafts, an ancient cottage industry that provides sustenance to many households. The antiquity of this folk art goes back 600 years to the days of the Maithili poet Vidyapati, who mentioned the plight of women stalk collectors in his poems.

And if all this was not enough, vetiver can help remedy severe cases of soil erosion. This is because vetiver is a tidy little plant that holds the soil in place and stays. It produces no seeds, and its long, tough roots help create natural terraces without spreading outwards. So it does not mix with the farmer’s crop when planted as hedges on farm boundaries or river banks.

This concept was used in Fiji a few decades ago when severe erosion endangered its sugarcane farms. After using vetiver, the land regained its health, erosion all but disappeared, and yields doubled. Today, the farmers of Fiji swear by this grass.

As the Vetiver Network International says, “If applied correctly, the Vetiver System could be an important tool to reduce erosion (by up to 90%), reduce and conserve rainfall-runoff (by as much as 70%), improve groundwater recharge, remove pollutants from water, reduce the risk of flooding, and improve economic benefits to communities.”

So the next time you are looking for an antidote to the heat of Indian summers, return to the roots (literally) and try this multi-faceted ‘wonder’ grass!

Edited by Vinayak Hegde

No comments:

Post a Comment