In Ladakh, the availability of locally grown fresh vegetables is usually restricted to summer months given how the region is characterised by extreme variations in temperature, particularly during the long and harsh winter season when temperatures hit as low as -30°C.

(Above image of a farmers inside the Ladakh Greenhouse growing tomatoes)

These long winters reduce the cropping season to barely four or five months in a year. Other factors include low precipitation largely in the form of heavy snowfall, high wind velocity, sparse plant density, thin atmosphere with high volumes of UV radiation and a fragile ecosystem.

As a consequence, most farmers pursue single-cropping, while double cropping is only possible in parts of Ladakh, which fall under the altitude of 3,000 metres above mean sea level.

The lack of locally grown vegetables necessitates obtaining them from outside the region through goods trucks that come from Manali (480 km) and Srinagar (420 km) and cargo planes from Delhi or Chandigarh where the freight costs sometimes go up to Rs 110 per kg.

Prices were soaring so high during the winter season that in 2019 the Leh district administration had to artificially fix the retail price of fresh vegetables like tomato (Rs 110/kg), okra (Rs 130/kg), cauliflower (Rs 110/kg) and spinach (Rs 110/kg), just to name a few. In fact, according to a market survey organised in February 2019, it was found that fresh vegetables are nearly three times costlier in Leh than they are in Delhi during the winter season.

To address this critical concern of the Ladakhi people, researchers at the Defence Institute of High Altitude Research (DIHAR) led by senior scientist Dr Tsering Stobdan have developed a new model of the Ladakh Greenhouse, a passive solar greenhouse, for local farmers.

“We studied the positives and drawbacks of traditional greenhouses, which are used extensively in Ladakh. Accordingly, four major changes were made. We replaced the polyethylene sheet with a triple layer polycarbonate sheet. This results in over 7-8 degree Celsius increase in temperature at night during the winter season since polycarbonate has much better insulating properties. Second, the unbaked mud bricks were replaced with stone walls since the latter has more heat absorbing capacity. The heat absorbed during day time is released back into the greenhouse at night. Third, we have constructed the greenhouse three feet below the ground level. Therefore, the ground heat helps in keeping the greenhouse warm in winter. Finally, we standardised the length, height and width of the greenhouse,” says Dr Stobdan, speaking to The Better India.

The three different standardised Ladakh Greenhouse Models include:

1) Commercial: 90x27x9 feet (length x Width x Height) — approximate cost: Rs 9.5 lakh

2) Medium: 60x24x8.5 feet — approximate cost: Rs 5 lakhs

3) Domestic: 32x18x8 feet — approximate cost: Rs 3 lakh

“The general perception is that the smaller the greenhouse the better is its heat retention capacity. However, we found that the reverse is true. Easily hand operated ventilators in these newly designed and developed greenhouses make it easy to regulate the temperature during summer months. Inside the Ladakh Greenhouse, the maximum temperature recorded is 45 degree Celsius in summer months. The lowest temperature recorded in peak winter months is 1 degree Celsius. That’s the reason why tomatoes are growing inside the greenhouse. Moreover, it is easy to operate. There is not even a single electronic gadget that farmers have to use here. It is entirely a passive solar greenhouse,” explains Dr. Stobdan.

“DIHAR developed the technology, but they have transferred it to the Department of Agriculture, UT Ladakh. The installation of the Ladakh Greenhouse is being done by the department. We are providing farmers with 75% subsidy for the construction of this greenhouse. Thus far, we have installed about 100 such greenhouses for farmers in Ladakh, which include the Medium type one and for domestic use,” says Tashi Tsetan, the Chief Agricultural Officer of UT (Union Territory) Ladakh.

“During the installation process, the farmer’s job is only to construct the walls. The department has to provide cladding materials (polycarbonate sheets), frame, door and window and ventilators, etc,” Tsetan adds.

Evolution of Greenhouses

Nonetheless, this isn’t the first version of a greenhouse to emerge in Ladakh. The first such greenhouse (glasshouse) in Ladakh was set up in 1964 at DIHAR, which was formerly known as Field Research Laboratory, for growing vegetables during winter months. When this didn’t work due to logistics and high costs, they conceived a low cost passive solar greenhouse in the late 1960s, where vegetables were ground in trenches covered with polyethylene sheets to prevent crops from getting frozen during the long and harsh winter season.

Given the lack of a retention wall above ground level and openness, the produce fell prey to stray animals. Making matters worse, the rate of adoption of this greenhouse was low. To address this, the first version of the Ladakhi Greenhouse was designed with mud brick walls on three sides (north, east and west), polyethylene cover on the south facing side and a roof on the side of the north wall. This innovation was popular for its greater heat retention abilities, allowing farmers in Ladakh to grow leafy vegetables like lettuce, spinach and coriander during winter.

Over the years, other agencies and organisations like GERES (Groupe Energies Renouvelables, Environnement et Solidarités), a French non-profit, Ladakh Environment and Health Organisation (LEHO), Ladakh Renewable Energy Development Agency (LREDA) and Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agriculture Sciences and Technology-Kashmir (SKUAST-K) have come with their modifications to the original Ladakhi Greenhouse model.

However, other concerns emerged with the first iteration of the Ladakhi Greenhouse. Certain vegetables like tomatoes, capsicum, cauliflower, cabbage, pumpkin and broccoli couldn’t grow because of freezing temperatures at night inside the greenhouse during winter months. During summer months, there was the issue of excessive heat generation inside the greenhouse with temperatures inside rising to a whopping 64 degrees Celsius. Farmers either would remove the cladding material or not use the greenhouse altogether during the summer season.

Also, the polyethylene sheet used in this greenhouse wouldn’t last more than five years because of high wind speeds, heavy snowfall, and other extreme conditions and required either replacing or constant repairs. Finally, these greenhouses wouldn’t last more than 10 years.

New and Improved Greenhouse

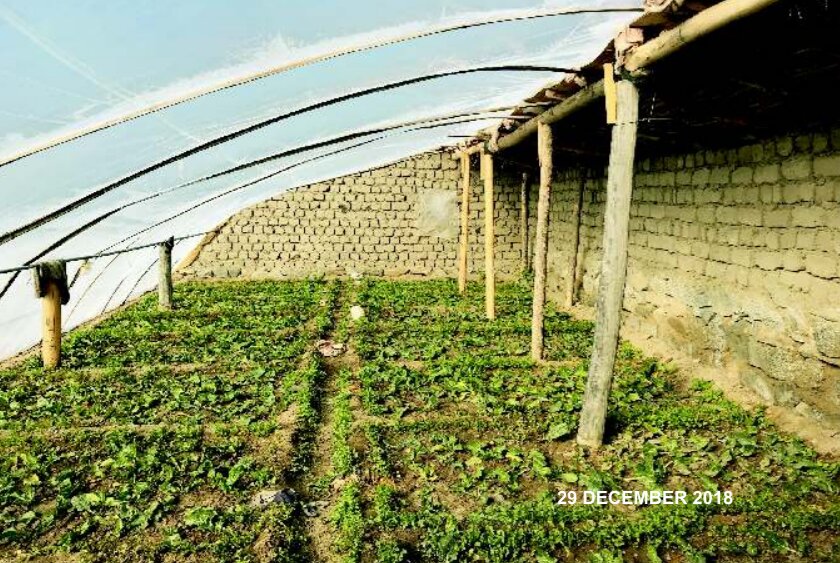

“We started working on this greenhouse in 2014. It took us three years to develop the first functional prototype. Our criteria for a functional greenhouse is growing tomatoes, a highly temperature-sensitive crop during winter seasons without any external heat/power source. In December 2017 we grew tomatoes inside the greenhouse for the first time. The new design was then studied further during the winter and summer for growing a variety of vegetables in Leh Ladakh. Our successful trials led to the designing of improved greenhouses of different sizes to meet varied farmer requirements based on availability of land and resources,” says Dr. Stobdan.

“I installed the Ladakh Greenhouse in October 2019 with support from the Defence Research & Development Organisation (DRDO). This is the third winter season where I have employed it. Prior to installing this greenhouse, I had installed two smaller ones covered in polyethylene sheets. The problem with these older greenhouses was that after November, they would freeze up inside. Last winter, I grew cauliflower, cabbage, spinach, methi, radish, tomatoes, mustard and coriander. After sowing these crops in October, by December I harvest my spinach. Cauliflower and the rest, I harvest in January,” says Tashi Tondup Angyal, a 56-year-old farmer from Thiksey, who was among the first adopters of a medium type greenhouse.

According to a document authored by nine researchers under the aegis of DIHAR in 2019, some of the salient features of the new and improved Ladakh Greenhouse include the walls on the east, west and north sides built with stone and cement, which they argue requires minimal maintenance. “The wall on [the] north side inside the greenhouse is used for fixing racks that can be used for different purposes. An outer mud-brick wall with insulation in between the two walls has also been studied,” explains the document (no link, a source shared it with me).

The second element to the new Ladakh Greenhouse is the use of “transparent UV stabilised triple layer polycarbonate panel is used for covering the south face of the greenhouse,” which they argue “has better heat retention capacity” and “retains an acceptable transparency even after 20 years of exposure to harsh climatic conditions of Ladakh”.

Another change to the earlier iterations of the old passive solar greenhouses is the use of sloped (to the north) Polyurethane Foam (PUF) roof which is durable, “has better insulation properties as compared to conventional wooden roofs” and “does not allow growth of molds and fungus”, which is a major concern in conventional Ladakhi greenhouses with wooden roofs.

Besides employing PUF, the other option is to go for a rust-resistant pre-coated “GI sheet topped with a layer of hay and soil as insulating material is also used for roofing”. Then, there are metallic or polycarbonate doors on the east well that require very little maintenance and manually, but easily operated, ventilators with metallic frames as well.

The temperature inside these greenhouses remains above freezing, even in December and January. With an extended shelf-life of up to 25 years, farmers can now cultivate crops all through the year.

“A variety of crops have been successfully grown inside the greenhouse during winter months— cauliflower, cabbage, broccoli, knol-khol, tomato and even mushroom. In a medium greenhouse one can obtain up to 325 kg of cauliflower/ greenhouse; 398 kg cabbage/ greenhouse; and 231 kg knol-khol/ greenhouse in Leh. These crops cannot grow well in traditional greenhouses. In the winter months, a variety of crops can be grown, which otherwise is not possible in a traditional greenhouse. During the summer months, a crop like cucumber would ordinarily enjoy a harvest from August onwards in the open field. Grown inside this greenhouse, however, harvest comes earlier in June, and we enjoy a higher crop yield of 4.5 kg per plant as opposed to 1.6 kg per plant on the open field — a 3-fold increase in crop productivity,” says Dr Stobdan.

“During the last winter season, after taking into account the vegetables we consumed in-house, we earned around Rs 75,000 from all the crops grown inside the Ladakh greenhouse. During the summer months, leafy vegetables like coriander, spinach and radish don’t grow very well. Instead, we grow tomatoes, okra, capsicum, brinjal, chilies, etc. Since we started using this greenhouse, I have cumulatively earned about Rs 1.75 lakh from all the crops grown inside excluding the items we consume in-house. Thanks to this greenhouse, my income from farming has increased. We are now easily able to grow vegetables during peak winter months in our greenhouse where we use polycarbonate sheets. In the summer, cauliflower sells for Rs 50 per keg, but by winter (January) we get about Rs 110 per kg,” claims Tondup.

But even without this financial assistance, Dr Stobdan believes farmers can break-even on the investment they made on the greenhouse in six years.

“Our target is to ensure locals have access to green vegetables during the peak winter season. We have seen in these greenhouses that when the temperature outside is -30 degrees Celsius, inside it’s 10 degrees Celsius. Besides farmers, entrepreneurs and other residents who can’t find work during the winter season, can also earn well during the winter season by growing and selling all these vegetables which have a ready market. We have even made a crop calendar for farmers, helping them navigate what they can grow throughout the year in the greenhouse. Besides installation, we also give them some training about what crops they can grow during spring, summer and winter seasons,” says Tsetan.

In the long run, the objective is to reduce dependence on fresh vegetables from outside the region — both during summer and winter. For this, the Ladakh UT administration’s target is to establish 1,000 greenhouses in Ladakh, including Leh and Kargil district, in the next two years.

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

No comments:

Post a Comment