As British-rule in India entered the 20th century, the time was ripe for a farmers’ agitation in undivided Punjab. Better lines of communication, transport, and the downward turn in the local agrarian economy allowed peasants in the region to take cognisance of their terrible plight. (Image above of Sardar Ajit Singh)

Rural indebtedness was on the rise from the late 19th century onwards. According to British civil servant Malcolm Lyall Darling, who was posted in Punjab in 1904, “The bulk of cultivators of the Punjab were born in debt, lived in debt and died in debt.” Reasons for their indebtedness were varied ranging from fragmentation of land from one generation of farmers to another to recurring famines (1860-61, 1867-78, 1896-97 and 1899-1901) and greater revenue demands from British, which often compelled them to borrow more from local money lenders.

Farmers accumulated further debt as a result of continuous litigation given the legal concerns they were constantly up against, especially in the Ludhiana, Jalandhar and Amritsar districts. Economist DR Gadgil, however, also points to another reason—sudden demand for Indian cotton in England due to the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861.

Although it brought short term prosperity, farmers also began to further rack up debt as money lenders lent their money freely against the mortgage of their lands or other assets, which down the line led to large scale distress sale of land.

Another major event important to this story is the construction of the Upper Bari Doab canal in 1879. As Amandeep Sandhu, a Punjabi journalist and writer explained in his 2019 book called Panjab: Journeys Through Fault Lines:

In 1879, the British constructed the Upper Bari Doab canal to draw water from the Chenab river and take it to Lyallpur (now in Pakistan and renamed Faisalabad) to set up settlements in uninhabited areas. Promising to allot free land with several amenities, the government persuaded peasants and ex-servicemen from Jalandhar, Amritsar and Hoshiarpur to settle there. Peasants from these districts left behind land and property, settled in the new areas and toiled to make the barren land fit for cultivation.

Adding fuel to the agrarian distress was the plague which first struck Punjab in 1897. By 1907, the plague had engulfed Punjab with a death rate of 62.1 per thousand (inhabitants). Local superstition suggested that the British brought the plague with them. In response to the devastating plague, the colonial government did little to control it and showed an utter lack of sensitivity. Instead of remitting land revenue, the British continued to increase it.

The final nail in the coffin was three laws that the colonial administration sought to pass — the Punjab Land Alienation Act 1900, the Punjab Land Colonisation Act 1906 and the Bari Doab Canal Act 1907.

“These laws reduced the peasants to sharecroppers; they could neither fell trees on these lands, nor build houses or huts or even sell or buy such land. If any farmer dared to defy the government diktat, he could be punished with eviction from the land… In 1907, in Lyallpur, [Sardar] Ajit Singh Sandhu — also Bhagat Singh’s uncle — spearheaded the movement that articulated the farmers’ discontent,” explains Amandeep Sandhu.

The Punjab Land Colonisation Bill forbade transfer of property by will.

“Only strict primogeniture [an exclusive right of inheritance belonging to the eldest son] in the future was allowed…In the future, land could only be transferred to a son, and if no sons survived, it could be transferred to the widow,” notes this paper by scholar Savindar Pal published in the Indian History Congress.

With no legal heirs, the land would become the property of the government, who could then sell it to any public or private developer. Making matters worse, the courts would have no jurisdiction in such cases, leaving no room for legal recourse.

Adding further fuel to the fire were the enhancement of land revenue and water tax, despite the precarious conditions under which farmers were operating.

The British increased the rate for using canal water through the Canal Colonies Bill 1907.

“It [Canal Colonies Bill] sought to change the very bases of land realisation in Punjab and attempted to deprive the farmers who had been uprooted from the districts of the Central Punjab to dig canals and irrigate the barren, but extensive crown waste lands in the Western Punjab [through the 1880s and 1890s],” notes Pal.

Launched in March 1907, Sardar Ajit Singh and his band of peasant leaders, agitators and stalwarts of the freedom struggle like Lala Lajpat Rai, led successful protests called the Pagari Sambhal Jatta movement, which eventually forced the colonial powers to repeal all three laws.

The cry of Pagari Sambhal Jatta (take care of thy turban-self respect O. Jat) was first articulated by Lala Banke Dayal, an editor of a local publication called Jhang Syal, during a public meeting in Lyallpur on 22 March 1907. After all, the turban is an important marker of faith for the Sikhs and seen as a symbol of dissent against tyranny. The falling of a turban was symbolic of defeat, and hence the cry of taking care of it from falling.

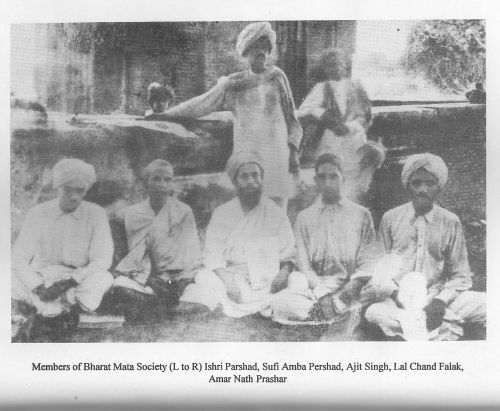

Bharat Mata Society

As the farmer unrest began to brew in the first years of the 20th century, Ajit Singh, Kishan Singh (Bhagat Singh’s father), and their friend Ghasita Ram established the Bharat Mata Society that was alternatively called ‘Mehboob-e-Watan’ with the ultimate objective of overthrowing the British government. Coming from a peasant family in Punjab, Ajit was acutely aware of the troubles that affected his fellow farmers.

Before launching into an agitation, Ajit Singh and his fellow revolutionaries—including Bankey Dayal, Lal Chand Falak, Zia ul-Haq, Kishan Singh, Pindi Das, Mehta Anand Kishore, Sufi Amba Prasad and Swaran Singh—studied the bills in detail and totally acquainted themselves with the implications of these laws.

In his autobiography, ‘Buried Alive’, Ajit Singh wrote, “We studied the bills in detail and fully acquainted ourselves with the implications of these acts and their detrimental effect on the peasantry.” The Bharat Mata Society organised meetings all over Lahore, explaining these bills to the people. In fact, those who wanted to know more about the farm bills were invited to their Mandir every Sunday in the city. These meetings would see gatherings of thousands.

Once they were well acquainted with the laws, Ajit Singh and his team of agitators organised several public meetings which would run from morning till evening in affected areas, including Lahore, Multan, Lyallpur, Amritsar, Gujranwala, Rawalpinidi and Batala. In these meetings, they would explain to fellow farmers the harm that these laws would do to them and not to pay further taxes or enhanced water rates. Assisting them in these endeavours were also the Arya Samaj.

But it’s important to note that the epicentre of the 1907 agitation was Lyallpur [now in Pakistan].

As Ajit Singh wrote, “I chose Lyallpur district as our centre for agitation because of it being a nearly developed area. It had people from almost all parts of the Punjab as also retired military people. Retired military people, thought, could be useful in bringing about a revolt in the army.”

Readying The Launchpad

It’s evident that the likes of Ajit Singh saw the farmers revolt as a springboard for a larger anti-imperialist struggle against British rule. There is an interesting anecdote in Ajit’s biography, where he mentions how Lala Lajpat Rai was initially hesitant in addressing a public meeting in Lyallpur because he suspected that the agitation was not merely limited to the farm laws.

“Lala ji was [at] first hesitant in addressing the meeting, but people shouted that they were anxious to listen to Lala ji. Seeing the public enthusiasm, he made one of his finest speeches, full of eloquence and spirit,” Ajit wrote.

As Ajit Singh’s nephew, the famous Bhagat Singh, noted in an article published in a local daily Pipal in 1931, about a public meeting 3 March 1907, “Just before this meeting, Lala ji told Ajit Singh that [the] government has made some amendments in [the] colony act. In the gathering, while thanking [the] government for this amendment, we should request [the] government to cancel the whole law. However, Ajit Singh made it clear to Lala ji that the agenda of [the] meeting was to inspire the public to stop paying agri-taxes.”

“By the end of March, the agitation had spread from Chenab to Jhelum, with leaders like Lala Lajpat Rai and Ajit Singh addressing meetings, touring the rural areas, seeking to integrate the movement in the Canal Colonies into the wider anti-imperialist struggle,” Neeladri Bhattacharya wrote in ‘The Great Agrarian Conquest: The Colonial Reshaping of a Rural World’.

Speaking to the British Parliament, Lord John Morley, who at the time was Secretary State of India, saud that between March and May 1907, all of 33 public meetings were held in Punjab. Of these, Ajit Singh was the key speaker in 19 of them. A powerful orator, Ajit ignited real passions into the hearts and minds of any Indian who attended these meetings.

It was one of his public speeches delivered on 21 April 1907, which got him in real trouble with British officials who charged him with the crime of sedition. As he said at the meeting:

The promises held out to us in the Proclamation of 1858 have never been fulfilled, and the rulers should not tell lies. The rulers have increased the land revenue four to six fold with the object of starving the Indians in order to benefit themselves. Be shot and do not mind, rather consider that you died of plague. Die for your country. One and half lakh of Eruopeans are nothing compared with 29 crores of Indians..Although they have guns, rifles and other arms, yet we will evaporize them in a minute, for God will come to the rescue of his oppressed people.

Eventually, Lala Lajpat Rai was arrested on 9 May, and Ajit Singh on 2 June, but not before the British repealed all three laws altogether.

“On May 26, 1907, Lord Minto, Viceroy and Governor General of India, put an end to one of the most intense popular peasant agitations in the Punjab Province by the exercise of a veto on the Colonisation Bill introduced in the Punjab Legislative Council in October 1906… At the back of the veto was the realisation that the colonial regime alienating the Punjab peasantry – the primary recruiting ground for the British Indian Army – had serious implications, even as it brought back haunting memories of the 1857 revolt,” Professor Indu Agnihotri, former director of the Centre for Women’s Development Studies, New Delhi, wrote in The Wire.

Both Lala and Ajit were deported to the Mandalay prison in Burma for six months for their speeches, and were released on 11 November 1907, but not before the colonial government faced a lot of violence and unrest.

“There were riots in Rawalpindi, Gujranwala, Lahore, etc. British personnel were manhandled, mud was flung at them, offices and churches were burnt, telegraph poles and wires cut. In Multan Division, railway workers went on strike and the strike was called off only when the acts had been cancelled. The Superintendent of Police in Lahore, Phillips, was beaten by rioters. British civil servants sent their families to Bombay and ships were chartered to take them to England if the situation got worse. Some families were transferred to forts,” wrote Ajit Singh.

”(General) Lord Kitchener got terrified since peasantry was becoming rebellious, military and police were unreliable. (John) Morely (then secretary of state for India) made a statement in the House of Commons that in all 33 meetings took place in the Punjab, out of which 19 were addressed by Sardar Ajit Singh. That increase in land revenue was not the cause of this unrest. It was with a view to finishing British rule in India that it was being used as a political stunt. The result of all this agitation was that all the three bills were cancelled,” he added.

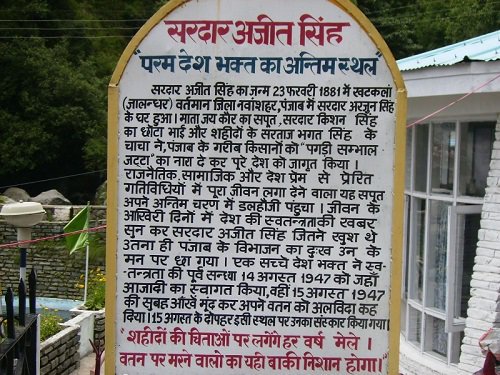

Ajit Singh would soon flee the country fearing further persecution, living in Iran, Turkey, France, Switzerland, Brazil (where he spent 18 years), Switzerland and even creating the Azad Hind Lashkar of 11,000 men in Italy before meeting Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose. He finally came to India on 7 March 1947, after Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru intervened to get him released from a German prison. He died hours after Nehru’s ‘Tryst of Destiny’ speech on the intervening night of 14 and 15 August 1947. But he made it back home to celebrate India’s freedom.

(Edited by Yoshita Rao)

No comments:

Post a Comment