“We as parents are very…upset. We have been confronted with this overwhelming situation…I lost my four-month-old baby and two-year-old son….It’s very difficult for us to survive and lead our lives…”

In 2011, Anurup and Sagarika Bhattacharya, an Indian couple living in Norway, put out this tearful plea to Indian authorities, asking them to help bring their children back home. In May that year, the Norwegian Child Welfare Services (CWS) had “confiscated” the couple’s children, Abhigyan and Aishwarya, citing “neglect” and “emotional disconnect” between the mother and the kids.

The children were forced into foster care by CWS, where it was ruled they would remain till they turned 18. Anurup and Sagarika were not allowed to see them.

What followed was two years of chaos and arduous custody battles, the intervention of the Indian government, several protests, and a sharp spotlight on a number of issues — cultural differences, racism, reception and treatment of mental health in women and children, and more.

Ten years on, Sagarika’s painful fight to have her children returned to her is being made into a movie starring Rani Mukherjee. Mrs Chatterjee vs Norway is set to release in May next year, almost exactly 11 years after Sagarika’s ordeal began.

So, in anticipation of the movie, here’s a look at what went down all those years ago, and how a mother finally emerged victorious in her lone battle for her children against a biased and broken system.

‘What if your children are taken away from you?’

In 2007, geophysicist Anurup Bhattacharya married Sagarika, and the two moved to Norway to start their new life. In 2008, Sagarika returned to Kolkata when she became pregnant for the first time with Abhigyan, and would remain here for a year. In this period, her child began to show “autism-like” symptoms. The two returned to Norway in 2009 to join Anurup.

By 2010, the couple placed Abhigyan in a family kindergarten and Sagarika became pregnant with her second child. Because Anurup was working long hours, she spent a lot of time alone with the boy.

At this time, Abhigyan began to show “concerning” characteristics, wherein he would start banging his head on the ground whenever he was frustrated. He also showed many signs of difficulty in communicating, and would often not make eye contact. Being heavily pregnant and weak, soothing Abhigyan became tougher and tougher for Sagarika.

To put things in perspective, Norway has an extremely strict child protection system, and a strong history of blanket regulations for all citizens living in the country, irrespective of cultural differences. For example, even a mild slap in the region is illegal.

The regulations fail to consider that in many countries and cultures, parents believe in the ‘spare the rod, spoil the child’ approach.

Regardless, in Norway, an anonymous tip is enough to send a CWS team to your doorstep. In the worst case scenario, you will be declared as an unfit parent and have your child taken away from you — a fate that was soon to fall upon Sagarika.

In November 2010, a team from the CWS showed up at Sagarika’s house after “receiving disquieting alerts about Abhigyan and his relationship with mother”. However, they left without further action upon seeing that she was pregnant. Next month, Aishwarya was born, and Sagarika took on a slow recovery process. At this time, Abhigyan began showing more signs of frustration when he would watch his sister be breast-fed, and taking care of the two kids, while managing a home while her husband kept busy with his job, got increasingly taxing for Sagarika.

Eventually, the kindergarten where she was sending her children began sending out alerts to CWS, and she was asked to sit for Marte Meo counselling for being “disorganised, unpunctual, lacking in structure and unable to establish a proper daily routine for herself or her family”. Meanwhile, the parents alleged that the social worker assigned to their case, Ms Middleton, was contemptuous, rude, and interfering.

“The lady officer from the agency used to often come to observe us. She used to come at any odd time, while I was cooking or feeding my baby. She just used to sit and keep looking at me. I didn’t understand their language very well so [I] wasn’t able to talk too much. But they never even indicated to me at any time that there was any problem, never gave me any warning about what they were writing. I never imagined that they could do such a thing as taking away my children. I was shocked when that happened,” Sagarika said.

She added, “Both of us knew about the counselling and observation part and we had openly agreed to it for the sake of our son. But I remember very clearly that when I did request a cancellation or a rescheduling of the home visits, I was told that this would not be possible. Even on days when I wasn’t feeling well, they insisted on coming. I remember being extremely uncomfortable on such occasions and I wanted to be alone with the baby, wanting to rest when the baby slept, but they sat there through everything, just sat there and observed everything, constantly writing down things in their files. On some days, I felt awful, I didn’t know what to do.”

On 11 May 2011, Sagarika left her son in the kindergarten and returned home for a meeting scheduled with the social worker and two others, where an argument reportedly broke out between the two parties. One of the care workers took Aishwarya under the pretext of taking her out for a walk till the situation cooled down. Some time later, the care workers called up the parents and informed them that both children were now in CWS custody. For two days, Anurup and Sagarika were forbidden from seeing their kids.

Two days later, when they went to the police station to see their children, an emotional Sagarika was unable to contain her outburst, which only made things worse for the couple.

“I don’t have words…I cannot explain what I felt…I remember I was crying, hysterical, shouting…Later, I heard they had recorded my behaviour as hysterical and taken that as further proof of my unsuitability as a mother. Tell me…how would you react if your children are taken away from you?” she had told this blog.

Until this time, Abhigyan had received no medical attention for his behaviour, despite the CWS’s involvement. An evaluation was reportedly conducted in March 2011, and the CWS gave the boy the diagnosis of an attachment disorder. Anurup and Sagarika claimed they were not aware of when and how their child was examined for this condition.

In November that year, the local County Committee on Social Affairs ruled in favour of the CWS, which was adamant that Sagarika should not get custody of her children. Abhigyan and Aishwarya were separated from their parents and placed in foster care. Anurup and Sagarika were allowed only three visits per year, for a duration of an hour each. All follow up appeals by the parents fell on deaf years.

A year-long battle comes to an end

By this time, Sagarika’s marriage began to deteriorate as well. In early 2012, the news hit headlines across India and Norway, and the Bhattacharyas put forth their side of the story. Several allegations of cultural differences and bias came to light. The couple claimed that the CWS had flagged issues such as the parents sleeping in the same bed as the children, using their hands to feed them, etc. However, Norwegian authorities were seemingly unaware that in Indian culture, these practices are more than normal.

The CWS continued to cite problems between Sagarika and her children, as well as Sagarika and Anurup, as an argument to keep Aishwarya and Abhigyan in Norway while their parents were in India. In February 2012, it announced that the children would be handed over to Arunabhas Bhattacharya, the children’s uncle and an unmarried dentist. Meanwhile, Sagarika and Anurup’s marriage had broken down, and an ugly custody battle was rearing its head.

Sagarika would go on to endure months of slander and hostility by several people, especially her husband and in-laws. Alongside, several reports began to surface detailing Norway’s implicit bias against NRIs, and the gaps in its child welfare system.

In April that year, in a small win, after intervention by the Government of India, the Norwegian court handling the case allowed the children to return to India, under the condition that they would live with Arunabhas.

But the battle was far from over for Sagarika, who filed a petition with Burdwan’s (West Bengal) Child Welfare Committee to have her children transferred to her care. She alleged that her husband’s parents had been reluctant to let her visit her children, and that the kids were not being looked after. The Child Welfare Committee seconded this claim in their report. In November 2012, Sagarika was declared psychologically fit to bring up her children.

NDTV reported that despite the ruling, police officials refused to let Sagarika reunite with her children. After months of back and forth between police officials, the Child Welfare Committee and the Kolkata High Court, Sagarika reunited with her children in April 2012.

On her reunion with her children, she said, “I am overwhelmed…as I am able to kiss them and [hold] them in my lap after one full year. I can’t express myself.”

In another interview, a beaming Sagarika told NDTV, “I have finally got my children back. My ordeal is over. Finally, I’m getting justice.”

Now over a decade later, Sagarika’s story is finding its way into the mainstream, after years of having been forgotten.

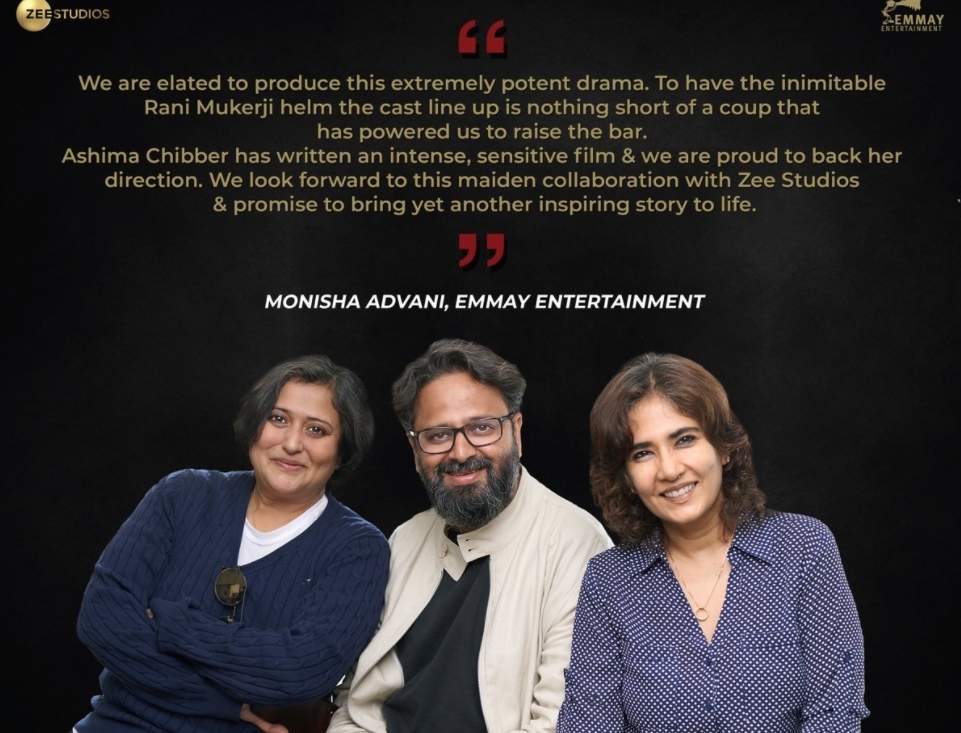

Mrs Chatterjee Vs Norway is said to be “an untold story about a journey of a mother’s battle against an entire country”, and will be directed by Ashima Chibber. Rani announced the movie this Sunday on her birthday and said that the movie is “one of the most significant films” of her 25-year-long career. “I started my career with ‘Raja Ki Aayegi Baraat (1997)’, which was a woman-centric film, and coincidentally in my 25th year, I’m announcing a film that is also centred around a woman’s resolve to fight against all odds and take on a country,” the Hindu reported her as saying.

Meanwhile, Sagarika, who had once gone 18 months without seeing her children, now lives a low-key and peaceful life with her kids in Kolkata.

Edited by Yoshita Rao

No comments:

Post a Comment